That’s Not a Mesa, It’s a Butte. Or is it? – Part 2

Berkeley Pit and other disasters.

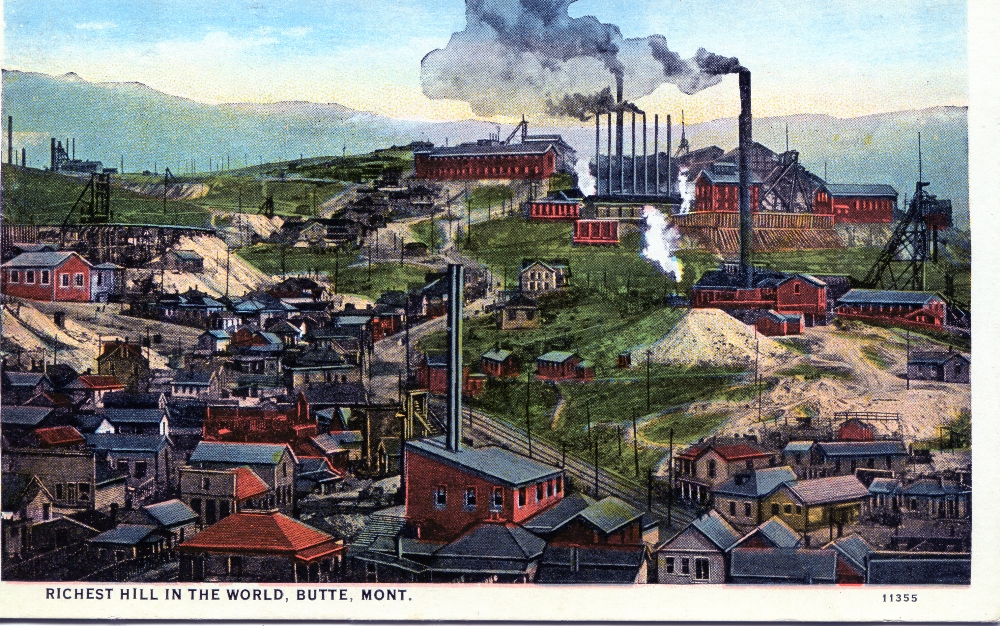

Within a few decades after the city was founded in 1864, Butte, Montana was known as the “Richest Hill on Earth” – a phrase that remains its motto to this day. Placer miners moving north and west from Alder Gulch discovered a relatively small amount of gold in Butte. However, while they were working the placer deposits of the creek that came to be known as Silver Bow, prospectors noticed veins of iron and manganese that cut across the hill and knob that they called Big Butte. When they put down prospect holes to test for the lode source of the placer gold, they found much less gold than they’d hoped for but they did find substantial assays of silver. Unfortunately, the remote area offered little hope of working those ores at the time.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in northern Utah just 350 miles away began to change that isolation. The railroad lowered the cost of transporting supplies to Butte and provided a cheaper avenue to ship high-grade ore from the city by the hill. Between 1874 and 1880, equipment and capital poured into the community and silver lined not the clouds but the pockets of capitalists and miners.

Soon after Marcus Daly arrived in town in 1876 to manage the Alice silver mine for the Walker Brothers of Salt Lake City, he noticed that the silver lodes being mined were showing more and more copper. An astute businessman, Daly recognized that with the electrical age dawning there would be demand for copper. He bought the Anaconda prospect, founded the Anaconda Mining Company, and what became known as the mining district was born.

In 1882 the district produced 4,500 tons of copper. A year later production more than doubled to something on the order of 11,250 tons. By 1884, four large smelters were operating and Daly was building what would become the world’s largest metallurgical plant at Anaconda, thirty miles to the west.

Within another dozen years, the five square mile mining district, established by three competing tycoons – Daly, W A Clark, and F Augustus Heinze – was producing 105,000 tons of copper a year. This amounted to more than a quarter of the world’s supply. Additionally, the by-product gold and silver the copper mining produced amounted to the equivalent of $500,000,000 a year in today’s dollars.

In those days the town looked something like this (from Richard Gibson’s site Butte History and Lost Butte)

Inevitably, the competing interests of the three main copper oligarchs began to clash in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as described in Carl Glasscock’s book, The War of the Copper Kings. In 1899, the Amalgamated Copper Company, a holding company established by the trustees of Standard Oil, purchased Day’s Anaconda Mining Company. Over the next 25 years, Amalgamated went on to acquire all of Heinze’s holdings and most of Clark’s. It then renamed itself The Anaconda Copper Mining Company.

As Butte’s mining production increased, so did its population. One common report says that sometime between 1910 and 1920, the city’s population reached 100,000. While this is possible, it’s not necessarily accurate. At its peak production in 1917-18, Amalgamated reported a payroll that included 14,500 underground mine workers so there was certainly a population boom.

Perhaps belying the 100,000 claim, U S census figures for Silver Bow County from 1910 (population of 56,848) and 1920 (population 60,313) indicates both a rapid expansion and an equally sudden contraction if the 100,000 number is to be believed. Still, it’s certainly conceivable that such an expansion and contraction occurred. Demand for mineral production was insatiable during the First World War and it dropped precipitously when the war ended on 11 November 1919. There’s also a 1917 census estimate that the population of the city of Butte was 93,981 with an additional 36,212 people in Silver Bow County. And, the census itself was known to undercount certain – mainly Asian immigrant – populations.

Whatever the accurate number is, the population was significant and the mine workers were active. From the 1890s to the 1930s Butte became known as “The Gibraltar of Unionism.” Not only did they battle for worker’s rights, the unions pushed Anaconda (known locally as “the Company”) to adopt cutting edge technologies in mining, milling, and smelting. However, this still didn’t prevent the single greatest hard rock mining disaster in the history of the United States.

Granite Mountain Mine Disaster.

At 23:45 on the night of 8 June 1917 a fire started in the Granite Mountain Mine. Alarms sounded quickly but by the time anyone could react, the signaling system on the deck cages had already burned out and rescue attempts couldn’t begin until 01:00 on the ninth. Acting counterintuitively, a young miner named Manus Duggan convinced 28 other miners to head into the heart of the mine and construct a bulkhead to isolate themselves from the gas and smoke.

Nearly 36 hours later, Duggan and the 28 other men made their way to the closest shaft station where they rang the alarm bell alerting startled rescue workers above to their presence despite those rescuers having been convinced by other rescued miners that no one could have survived in the depth of the mine. A total of 25 of the men were rescued. Sadly, Duggan, who returned to the tunnels to search for his few remaining companions, was not among the survivors. A similar fate befell J D Moore who, like Duggan, had barricaded himself and his crew of six men deep in the mine. Five were rescued 56 hours after the initial alarm but Moore was not among them.

In all, 168 of the 410 men who began the shift died as a result of the fire that started in the Granite Mountain Mine and it remains the highest death toll from any U S mine disaster. There’s an expansive memorial located a bit north of the neighborhood called Uptown Butte in the community of Walkerville.

As you drive up Main Street, there are other reminders of the dangers of underground mining. You pass markers noting the 43 men who died in “The Original” Butte’s first copper mine and the 79 who died in “The Steward.” It’s estimated that over a period of slightly more than a century 2,500 men died in underground mines in Butte. About two miles into the climb, you reach the memorial to Granite Mountain.

The Berkeley Pit.

Although the mega demand of World War I had abated, the Company, now known as ACM continued its profitable operation. With the outbreak of the Second World War, ACM experienced a second stretch of enormous profitability. It used those profits to launch an effort called the Greater Butte Project (GBP) to mine the ores of the Hill at a much lower grade but at a very much higher volume by a process called block caving. (Block caving is an underground hard rock mining technique that undermines an ore body causing it to progressively collapse under its own weight.)

In 1955, ACM began excavating a small experimental pit at the site of the Berkeley mine. (Open pit mining is essentially the surface version of block caving.) The operation at Berkeley proved so successful that by 1958, the Company had all but scrapped the GBP to concentrate its effort at the Berkeley site and in 1963 it sunk Butte’s last shaft.

While this was profitable for ACM and safer for the miners, it created a new problem for Butte. The details are in the next post.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026