In these food related posts, I hope you’ve been surprised to learn how the Portuguese brought tempura to Japan and Vindaloo to India and you’ve met some typical Portuguese preparations such as bifanas and alheira. A few more remain.

Good for the heart.

I think any Brazilian worth their salt will claim feijoada as that nation’s national dish. They might assert that feijoada was created by African slaves using ingredients accessible to them. These would have included black beans, and parts of the pig that had been rejected by the slave-masters. And, while the black beans that are commonly used in Brazilian feijoada are native to that country, it was probably homesick Portuguese that adapted the recipe to locally available ingredients and that the truth of the dish’s origin likely lies on the Iberian Peninsula.

As the Roman Empire spread across Europe, they spread the idea of stews combining meat (particularly cuts of pork), beans, and vegetables that became cassoulet in France, fabada in Spain, and feijoada in Portugal where each region produces its own version using different types of beans. For example, in the northeast of Portugal you can find Feijoada à Transmontana (from the area called Trás-os-Montes) which uses kidney beans. In the northwest of the country along the Minho River you’re more likely to find cannellini or white beans.

The preparation traditionally adds different types of chouriços, bacon, and pork cuts such as ribs, shank, feet, and ears. Carrots and cabbages are added later and everything is slow cooked in the same pot.

[Photo from196flavors].

Of course in the south and along the coast the recipe has been adapted to use fish and seafood – Feijoada de Marisco. It’s likely that you’ll find local versions of feijoada in Mozambique, Macau, Timor, or anyplace you can find Portuguese influence.

It’s the final countdown.

Two more important staples of Portuguese cuisine remain – sardines and bacalhau – but I’m only going to discuss the latter. Sardines are abundant along Portugal’s coast and are a staple of the Portuguese diet but, while freezing has made them available year-round as are the canned varieties most self-respecting Portuguese will eat grilled sardines only during the May to October season.

{Photo from 196flavors].

Since this is a winter trip, I won’t discuss sardinhas.

Things are about to get salty.

This section header could have both a literal and a figurative meaning. Literal in the sense that I’m going to write about bacalhau (cod, or more accurately salted cod). Figurative in the sense that my Portuguese friends might think I’m giving short shrift to this most Portuguese of ingredients.

As a country with nearly 1,800 kilometers of Atlantic coastline Portugal’s love affair with food from the ocean is understandable. Visit any local mercado in Lisboa or anywhere near the coast and you’ll find it teeming with freshly caught fish. Visit a standard grocery store and it will likely also be teeming with salted cod.

[Photo from lisbonlisboaportugal].

It may be a bit harder to understand Portugal’s love affair with a fish whose native habitat is the far North Atlantic.

I’ll begin the story at the time Portuguese explorers reached Newfoundland in 1497. The Portuguese had been using salt to preserve other fish for several centuries and they applied this method to Atlantic cod. They would catch the cod, gut it, cut it into pieces, then put it inside wooden barrels with lots of coarse salt.

Salted cod was nutritious, easy to transport, long lasting, and cheap so it became not only a food source aboard the ships during the Portuguese sea expeditions to the Americas and Asia, but also came to be regarded as the “meat of the poor” in Portugal. At some point, the Portuguese started referring to salted cod as ‘o fiel amigo’ – the faithful friend.

Not surprisingly cod fell in and out of favor over a 500 year period but early in the 20th century the dictator Salazar labeled it a key food for industrial workers and kept the price artificially low. The government also embarked on a propaganda campaign spreading the narrative that salted cod was an integral part of Portuguese heritage.

Today, even though 70 percent of Portugal’s cod comes from Norway, it’s said in Portugal that there are 365 ways of preparing bacalhau, and over 1,000 ways of serving it. Truth or exaggeration, cod is a central ingredient in Portuguese cuisine. Here are a few examples:

Bacalhau à Brás.

Said to have been created by a tavern owner named Braz in Bairro Alto in Lisboa, it is a combination of bacalhau pieces mixed with potatoes, eggs, onions, olives, chopped parsley and garlic.

[Photo from pingodoce.pt].

Bacalhau com natas.

This unique preparation is one of the few that includes cream. The basic recipe starts with shredded codfish that’s layered with potatoes, fried onions, and cream then baked. As seen below, it can be topped with melted cheese and served in a casserole.

[Photo from vaqueiro.pt].

Pasteis de bacalhau or bolinhos de bacalhau.

These codfish cakes or fritters are made with mashed potatoes, codfish, eggs, parsley and onion. They created quite a moment for me on my first visit to Lisboa.

If you’re in Lisboa and the south of the country you’ll likely see them called pasteis. In the north, you’re more likely to see the term bolinhos but they are essentially the same dish.

Bacalhau a lagareiro.

If you like high quality olive oil, you will almost certainly like bacalhau a lagareiro which is primarily cod roasted in olive oil. The dish also includes potatoes abundantly coated with Portuguese olive oil, onions, and garlic. As it’s roasting, the olive oil naturally emulsifies with the juices of the fish to create a sauce.

[Photo from oglobo.com].

Pataniscas de Bacalhau.

This is another type of deep fried cod. In this instance the fritters are made with eggs, flour, cod, parsley and onion. The ingredients are mixed together and deep fried. Served alone they’re an appetizer. With rice, a main dish.

[Photo from eatlikeaportuguese].

Arroz de bacalhau.

The basic ingredients are salt cod, rice, onion, garlic, olive oil, and leeks. The dish is simmered in vegetable or fish stock and white wine. Some variations add beans or vegetables and it’s usually garnished with cilantro and black olives.

[Photo from saborintenso].

There you have six cod recipes you can find in Portugal. (Seven if you remember the balcalhau as it appeared in the Consoada I made for my Christmas Eve dinner.) I encourage you to try any or all of them. Or, you can believe this:

Forget about your sin – give the audience a grin.

It’s time to return to our tour. When we left Livraria Ler we needed to walk less than 200 meters to our next destination Aloma – a small neighborhood pastelaria that has been serving the Campo de Ourique neighborhood since 1943. It drew its name from a movie called Aloma of the South Seas that was showing at the theater next door.

João Castanheira acquired ownership of the shop in 2009 and in 2011, Aloma won a prize for producing the best pastel de nata in Portugal a feat it repeated in 2013 and again in 2015. It also finished second in 2019, 2021, and 2022. So, of course, we each indulged in one of the delicious treats and P & K each had a bica. I stubbornly and stodgily refused to drink anything but chá preto. (Aloma has a second location in El Corte Inglês – the large shopping center in São Sebastião and a satellite location in Amadora operating under the name Confeitaria Glória.)

Photo from lojascomhistoria].

Like art and music, food can be very much a matter of personal taste. Ines certainly expressed her preference for the pasteis de nata at Aloma. It was an unquestionably tasty morsel and to my less than epicurean taste buds, was probably closest in taste to the pastel de Belém. However, I also have a notorious sweet tooth and still prefer the noticeably sweeter ones at Manteigaria.

And finally.

One stop remained before we ended our food tour and it was even closer than Aloma was to Livraria Ler. We headed back toward the Mercado and landed at Adega e Sabores de Portugal. This small shop on rua Coelho da Rocha specializes in selling regional Portuguese products. Here we sampled queijo de ovelha sotonisa curado – a cured sheep’s milk cheese seasoned with paprika from the Nisa region. It was accompanied, as many of Portugal’s sharp tasting cheeses are with doce de abóbora a sweet pumpkin preserve that softens the cheese’s bite. And, of course, you can’t have cheese without wine so we sampled Casa Ermelinda Freitas Moscatel de Setúbal dessert wine.

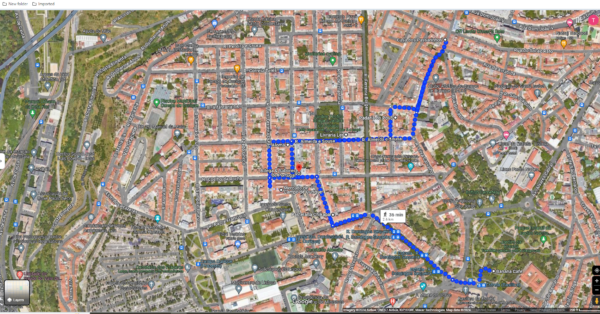

If it sounds like a long day, it was. If it sounds as though we walked a lot, we didn’t. Here’s a Google maps approximation of our entire day showing a total of less than three kilometers.

(You can also see the Cimetério dos Prazeres at the lower left.)

If it sounds like we were a happy crew,

You can judge for yourselves.

Quite an incredible day described in all of your interesting and informative posts. I learned a lot more reading your blog. You make an incredible host!

Muito obrigado, meu amigo. It’s easy to be a good host when you have terrific guests. I certainly enjoyed having you visit. And there are a few highlights for you to come (at least pictorially).