sister of the shield and trident

Today, after two brief stops, one planned and one a bit of a surprise, we’re leaving Kangaroo Island and will be back on the mainland where we’ll remain together as a group for 12 more days. However, that won’t be the end of my time in Australia. When RS is done with me (or I with them), I’ll be off to Hobart for four nights and another four in Melbourne. For now, let’s start with wrapping things up on Kangaroo Island (KI).

First stop Reeves Point

This was the unplanned stop and, as it turns out, the only one for which I have any pictures from the day. Curiously, among the first things I noticed was the black swans swimming in Nepean Bay.

I found this curious because I’d seen no black swans in Perth in the river that was named for them.

So, what’s the importance of Reeves Point? Perhaps you recall from the post The light was playing on its surface that the colony of South Australia was settled in 1836 and established as the first free British Colony. It was here, on 27 July of that year that the first settlers arrived and, according to a historical sign at the sight, “Two year old Elizabeth Beare, carried ashore by Robert Russell, was probably the first colonist to set foot upon the land.” She was rowed ashore from the Duke of York, the flagship of the South Australian Company.

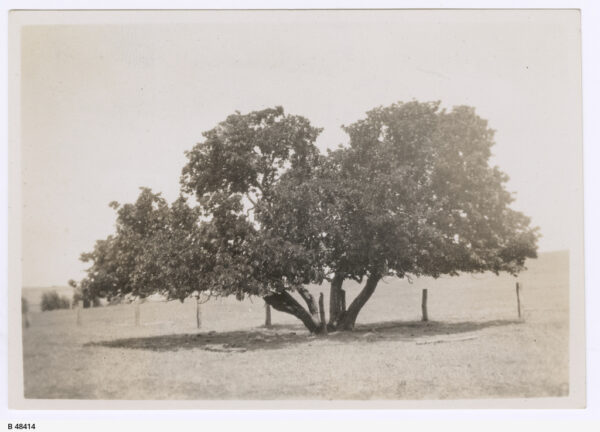

The British colonists, as was typical of the time, brought myriad plants and fruit trees with them planting an orchard of almond, mulberry and carob trees. Today, the lone survivor is a sole mulberry tree seen here in 1928.

[From State Library of South Australia, B-48414]

It’s believed to be the oldest living tree in SA. Here’s a photo taken in 2024.

The site received its current name sometime in the late nineteenth century but there’s no definitive record whether it was named for Samuel Reeves, a sheep farmer who came to the island in 1850 or for his son Augustus. This made Reeves Point an interesting detour made slightly more interesting by the fact that one of the RS travelers shares a surname (though no known relations) with this spot of historical importance.

The next items on the RS agenda were a stop at “False Cape Wines for guided wine tasting accompanied by platters featuring local produce” and, after riding the ferry back to the mainland at Cape Jervis, a “Field Trip Fleurieu Peninsula”. I have no photos and little memory of either of these activities. This is certainly unsurprising regarding the wine tasting because I rarely drink wine and it matters not at all to my palate whether I’m tasting a cabernet, a shiraz, or even the wine mentioned in this NSFW clip.

And if we got off the bus anywhere during the Fleurieu Peninsula field trip, it inspired no photos. (It’s also possible that if we remained on the bus the entire time, I dozed off more than once because long bus trips can inspire that in me.)

In lieu of that, I’ll fill in some other information about the island where we’ve spent the past few days.

The cat problem

(All blessings come with a curse.)

Yes, KI has a cat problem. Really, it’s a feral cat problem similar to the one faced on the mainland. The biggest differences are in numbers and size. Mainland Australia has between 2,100,000 and 6,300,000 feral cats and a total land area of 769 million hectares. KI has between 1,000-2,300 cats on 440,ooo hectares. But the cats are problematic in both places.

We’ll never know if the first cats arrived on KI with those first settlers in 1836 (Cats were often a part of a ship’s complement whose principal duty was pest control.) but it’s possible that, just as they brought non-native plants, some settlers brought cats sometime in the 19th century.

Recall that when Matthew Flinders and his crew arrived at KI, they easily slaughtered 31 unwary kangaroos. The kangaroos were unwary because they had no natural apex predators on the island. The same was true of the endemic pygmy possums,

[From Inhabitat.com]

southern brown bandicoots,

Kangaroo Island dunnarts,

[By Kangaroo Island Landscape Board CC BY 3.0 au]

and numerous birds and reptiles. No apex predators, that is, until the arrival of humans who brought

[Photo From Andrew Cooke Pestsmart.org.au]

cats.

In other parts of Australia, cats typically became feral within 20-40 years of their introduction. If the same pattern held true on KI, it’s reasonable to conclude that the first feral cats were wandering the island before the turn of the 19th century. They would have quickly adapted to the local environment and became apex predators and, absent other competition, their numbers thrived and spread unchecked.

Although the cats haven’t yet hunted any KI species to extinction, it’s estimated that they have played a significant role in the extinction of 27 mainland species. S, our site coordinator, has family and property on KI and has played a role in the construction of a fence on the Dudley Peninsula that’s helping to reduce the feral cat population. She spoke of it frequently and pointed out the fence whenever our bus passed it. Here’s an ABC report (from after the 2019 wildfires) on some of the other measures that have been undertaken both individually and collectively.

Bodacious Baudin & pre-internet Freycinet

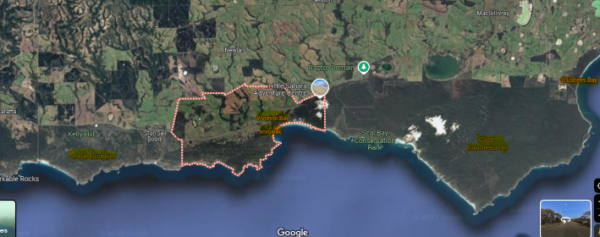

I’ve highlighted a few place names on the map below taken from Google.

If you’re having trouble reading them, they are from west to east, Cape Bouguer, Vivonne, Cape Gantheaume, and D’Estrees Bay. What are all these French place names doing on a British Colony particularly since relations between the two countries in the nineteenth century were, as they had been for centuries, contentious.

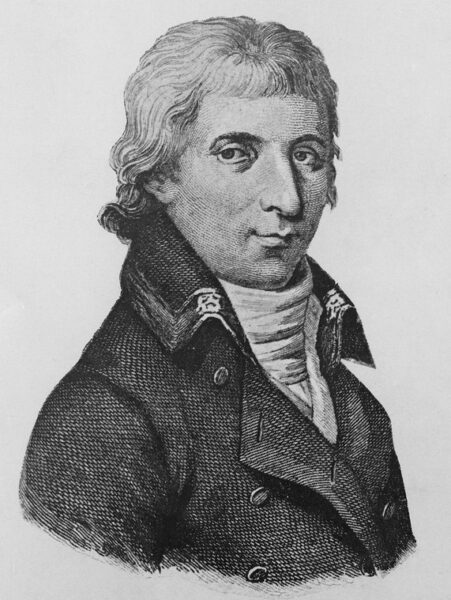

When Matthew Flinders and his crew landed on KI on 21 March 1802, the captain was aware that a team from France had set sail several months before his. Nicolas Baudin

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

led the French expedition and was likely sailing along the island’s west coast at about the same time. The two ships met accidentally on 8 April 1802. Since both were sailing under orders to chart the ‘unknown coast’ of the Southern Land and had no present knowledge of any hostilities between their home nations, they had a peaceful exchange of information at a place Flinders later named Encounter Bay.

Many of the names bestowed by Baudin’s expedition remain in use. Interestingly, however, most of those names were not the ones chosen by Baudin who died in Mauritius on the return journey. According to the site Encounter 1802-2002,

Louis de Freycinet drew up the charts and maps of the expedition. Baudin had been discredited by both early deserters of the expedition and the returning travellers, and French authorities were embarrassed by the apparent failure of the voyage. Freycinet bestowed his own choice of place names to South Australian locations, disregarding names that Baudin had recorded earlier.

It’s almost exclusively Freycinet’s names that remain in use today.

It’s just across the square

As I noted in the introductory post, this RS trip had more included meals than any other in my travel history and I thought it detracted from the experience in some ways. On the other hand, I’m frugal enough that I chafe against buying an outside meal when I’ve already paid for one within the tour structure. When I saw that our supper in Adelaide was listed as “At accommodation” I broke my own rule.

Before the trip I’d read about an Indian restaurant in Adelaide called Jasmin that had won many awards and had been consistently named as being among the 100 best restaurants in Australia. Now, given that the population of Australia is just a bit above 27 million people, it would be a greater achievement on the basis of population to be named among the 100 best restaurants in Tokyo (The population of Greater Tokyo is 41,000,000.) or a little better than say New York or Los Angeles.

Still, it’s a worthy achievement and, as it turned out, was directly across the square from our hotel. I told S and J not to expect me for dinner, left the hotel for a bit of a walk about the neighborhood to build my appetite, and, after twice walking past the inobtrusive door, found my way downstairs and settled in for break from the RS routine.

I had an entree (the American equivalent is an appetizer) vegetable pakoras, a main of fish curry prepared in the Goanese style (Goanese as a hat tip to the Portuguese influence on Indian cuisine) with garlic naan and a beer. It was worth every extra penny.

Tomorrow is another quiet day. We’ll fly to Darwin and immediately board a bus to Kakadu National Park where we’ll spend the next two nights. Along the way, I’ll offer some new lessons from and about Australia’s First People.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026