The Gray City of Kings.

If you do basic cursory research about the history of Lima, you’ll probably read that Francisco Pizarro established the Ciudad de los Reyes (City of the Kings) on 18 January 1535. For him, this was the date of the Epiphany and it inspired his choice for the name of what would become the capital of the Viceroyalty of Perú when that entity was established in 1542. If you’re Christian you might be confused by the date because on the Gregorian calendar in use today, Epiphany falls on 6 January. However, the Julian Calendar, used at that time, placed the date of the Epiphany on the eighteenth.

(People sympathetic to the Inkas or those who are appalled by his double dealings might think that fate ultimately dealt Pizarro his justified comeuppance. After plundering the wealth of the Inkas and tricking Atahualpa before capturing and executing him, Pizarro became embroiled in an internal conflict with another of the conquistadors – Diego de Almagro.

De Almagro had assisted in the conquest of Perú and subsequently sought his own fortune by taking his troops into Chile. Once there he encountered fierce resistance from the local Mapuche people and never discovered the riches that had been evident in the heart of the Tawantinsuyu.

Urged by his senior explorers to abandon Chile, Almagro returned to Cusco where he claimed the city and imprisoned Francisco Pizarro’s brothers Hernando and Gonzalo. Francisco sent an army led by Alonso de Alvarado to free his brothers but Almagro won the day and Alvarado joined the two Pizarro brothers in prison.

After Gonzalo and Alvarado managed their escape, Francisco negotiated Hernando’s release by promising to cede Almagro control of Cusco. It was a promise he never intended to keep and he immediately set about reassembling his army. Sometime in 1538, word reached Pizarro that Almagro had fallen ill and he launched his attack emerging as the victor and executing his erstwhile ally in 1538.

What he failed to do was execute Almagro’s 18-year-old son Diego II. On 26 June 1541 less than three years after his father’s execution, 20 of Diego’s supporters stormed Pizarro’s palace in Ciudad de los Reyes and stabbed the conquistador to death a year before Spain declared the Viceroyalty.

A part of me wishes that Diego himself had stabbed Pizarro so I could imagine him saying, “Hello. My name is Diego de Almagro. You killed my father. Prepare to die.” )

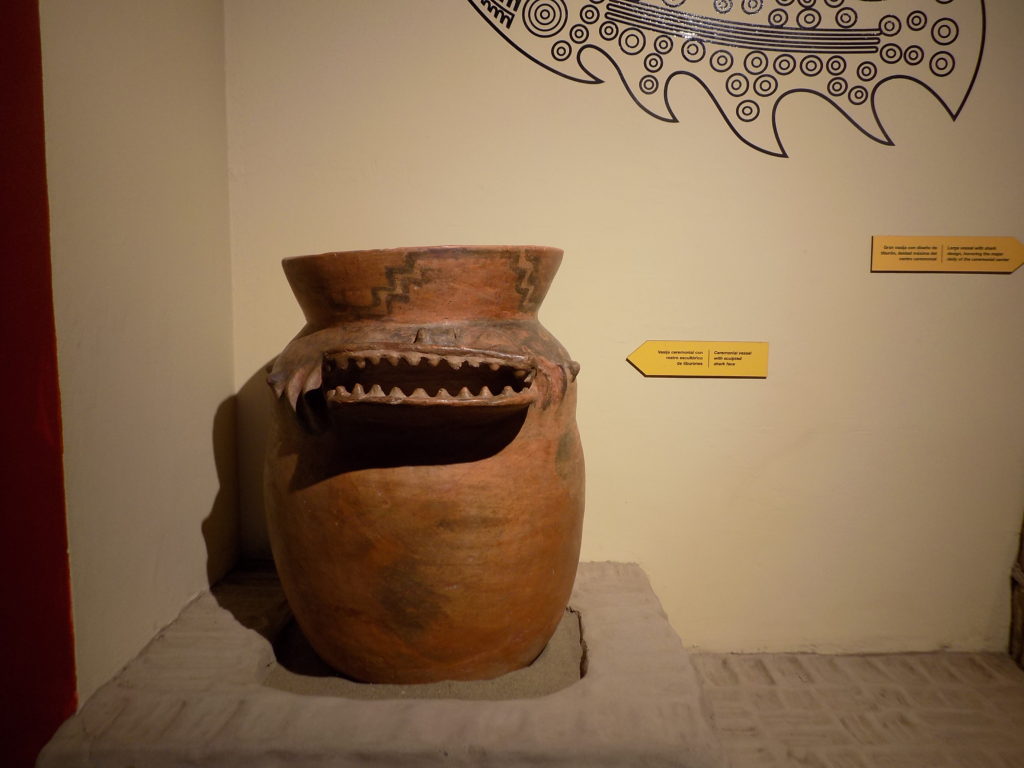

Of course, indigenous people had long inhabited the area before Pizarro established his city. Evidence of stone tools along the Chillón River dates to between 8,000 and 7,500 BCE. Over the millennia a succession of cultures held sway over this coastal territory including the Lima culture that left artifacts such as this

and at least two cultures I’ve mentioned previously – the Wari and the Chimú. The latter was ultimately incorporated into Inkan territory.

De donde el nombre Lima?

On this journey, we’ve encountered one city whose official name significantly exceeds its commonly used name – Paraguay’s capital – Nuestra Señora Santa Maria de la Asunción – shortened to simply Asunción. In the United States. The city we call Los Angeles is officially El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de Porciuncula. So why didn’t local people simply shorten Ciudad de los Reyes to Los Reyes?

Keep in mind that Lima is in a desert with its water provided by three principal rivers – the Rimaq, the Lurin, and the Chillón. While the earliest settlers in the area would likely have subsisted mainly on fish, over time they developed an extensive irrigation system that effectively created an oasis and allowed for some agriculture. This, together with an exceptional harbor at Callao, was among the factors that induced Pizarro to establish his capital there.

According to my research, there’s evidence that the Inkas called this area Rimaq – evoking both the river and a phonetic similarity to the Quechua word rimay which means ‘to speak’. They had built an oracle (rimay taki) within what is now the old city.

The change comes down to phonetics. The local Quechua dialect doesn’t distinguish between the lateral approximant /l/ and the alveolar approximant /r/ so, to Spanish ears, their pronunciation sounded more like Limaq than Rimaq. At the back end of the word, the Spanish, who preferred the simpler Limaq over Ciudad de los Reyes, had difficulty wrapping their tongues around the velar stop <k> and dropped it. Thus, the Spanish likely turned the local Quechua dialect Rimaq into Limaq and Spanish tongues then reduced that to Lima.

What’s gray got to do, got to do with it?

When I first wrote about Lima I mentioned la garúa – the weather phenomenon that creates a nearly perpetual mist that dominates the winter months. A survey of data by worldatlas lists the cloudiest cities in the world in terms of sunshine duration. This is how the site defines the term:

Sunshine duration is a commonly used climatological indicator. Sunlight duration is expressed as an averaged value of sunlight hours over several years and is used as an indicator of the general cloudiness of a place.

It lists Lima as having an average of 1,230 hours of sunshine per year making it the sixth cloudiest city in the world. As the site limaeasy shows, in winter Lima looks like this

more often than not. Hence, its residents often call it La Gris (The Gray).

No lemons or limes but still another nickname.

Although the city’s residents still sometimes refer to Lima as “Ciudad de los Reyes,” it’s not used on a par with La Gris. Some might claim, however, that the nickname El Pulpo (The Octopus) is popularly equivalent to La Gris. While the city’s core is relatively small, the metropolitan area is one of unregulated sprawl.

Like many European cities, Lima once had a surrounding wall. It survived a massive earthquake in 1746 but was eventually demolished in 1868. This opened the space for the first major avenues such as Paseo de la Republica and Arequipa and, perhaps more importantly, prompted the construction of railways and tram lines.

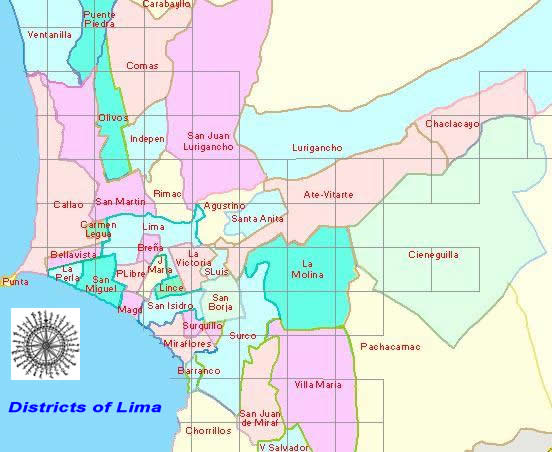

Lima experienced relatively steady and what appears to be at least superficially organized growth from the middle of the 19th century until the end of the Second World War. Industrial development was largely confined from the city westward to the Port of Callao. Prime residential developments spread along the coast south of Callao from Barranco through Miraflores to Magdalena, and lower-class suburbs grew in the east toward Vitarte, Ate, and La Molina.

When migration from rural areas to the city began in earnest after World War II ended, tens of thousands of people moved into the city annually settling wherever they could find space. This effectively ended any semblance of organization. These migrants built barriadas (shantytowns) by building housing constructed from cardboard, tin cans, wicker matting, or any material that could provide even a semi-permanent shelter.

Over time, bricks gradually replaced tin and cardboard and these areas coalesced into the urban districts of La Victoria, Lince, San Isidro, and other more permanent communities that came to be called pueblos jovenes (young towns). They now house about a third of the metropolitan area’s 8,200,000 people. The unbridled growth reaching in every direction from old Lima has led Limeños to dub their city El Pulpo. This map from Peru-explorer might provide some perspective.

It was an uneventful bus ride until…

The bus left Paracas a few minutes behind schedule but the uninterrupted ride north along highway 1S gave me some confidence we’d arrive near the scheduled time of 19:00. Then we ran into Lima traffic and ended that hope.

Meanwhile, Jill had wrapped up her extension to the Amazon and was overnighting in Miraflores on her way to Santiago. She reached out to me on WhatsApp to tell me she’d learned that we’d be staying in the same hotel. That message came at 19:33. My reply was that I was still on the bus and that we’d better plan to meet for breakfast rather than dinner because it had taken us more than half an hour to travel a few kilometers and I had no idea when I’d eventually arrive.

We settled on a time to meet, wished one another good night, and I began thinking about how I’d spend my last day in Perú after breakfast with Jill.

Although the bus was late, Alejandro, the same driver who’d taken me to the bus Sunday morning, was waiting for me when I arrived. Much to my relief, he told me that he’d also take me to the airport the next night. Knowing I had reliable transportation, I slept less fitfully than I had during my previous stay in Miraflores.

For those among you who missed my reference to The Princess Bride, you have my sympathy. Nevertheless…