The calendar turned a page and January became February. Only two weeks remained before I’d again leave Lisboa. And while it was my intent to pass the majority of those days as though I was a resident of the city, there remained neighborhoods to explore and cultural attractions to see. Today I’ll report on a bit of both.

I began my morning journey in the general direction of the neighborhoods of Estrela and Santos by walking through Chiado and Bairro Alto to the Museu do Marioneta (Puppetry Museum) but on my way I spent some time wandering through the still charming neighborhood of Madragoa. Perhaps my judgement is a bit rash – and considering that it was made based on walking through the neighborhood for half an hour or so rashness of judgement would be a valid critique – but Madragoa felt to me like a more authentic Lisboa – area one not crowded with tourists or overrun by expats – than many of the other neighborhoods I’d walked through. The Lisbon Portugal Tourism guide says that it was in this neighborhood that covering the exterior of buildings with tiles began. (On my way home, I’d walk down the hill to Santos which is a hub of construction and considerably less charming than Madragoa but also less hilly and more direct though slightly longer than any of the routes suggested by Google Maps.)

Walk 250 meters up a mildly steep hill along rua da Esperança from rua Dom Carlos I and you’ll reach the Puppetry Museum that occupies the former Convento das Bernadas – a building that dates from the middle of the 17th century and that had a long and interesting history before becoming home to the Museu da Marioneta in 2001. Although it’s in Portuguese, the video below provides a brief (and I hope comprehensible) overview of that history.

From ancient Greece and Egypt to Avenue Q.

Before you become too cynical about a museum devoted to puppetry or even think it passé in our hyper-technological century, think about how familiar you are with the subject and not just from your childhood. If you’re British you might think of Punch and Judy, If you’re French it might be Guignol and Gnafron, from German speaking Europe comes Kasperle. Americans who are old enough might think of Howdy Doody or Shari Lewis and Lambchop or, more recently, Sesame Street or the Muppets. And, here in Portugal, perhaps it’s Polochinelo and traveling troupes of Robertos. However, as adults, we’re still entertained and educated by puppets. Think of the Broadway show referenced above. It debuted in 2003.

Since the museum doesn’t confine its exhibitions to puppetry in Portugal, I won’t confine my narrative either. The Greek historian Herodotus provides us with the first historical mention of puppets sometime in the fifth century BCE although his writing itself indicates that they have their source in Egypt thus predating his description of “cubit-tall figures, pulled by strings, with moving phalluses as large as their bodies, accompanied by a flute-player and women singing hymns to Dionysus…” Certainly, the discovery of puppets carved from ivory or fashioned from clay in ancient Egyptian tombs and hieroglyphs portraying walking statues supports this notion. However, there’s also ample evidence that various cultures globally had or were developing their own forms of puppetry by this time. This looks to have been particularly true in India where ancient writing, songs, and folk tales allude to puppets.

Life may be scary only For Now but it’s only temporary.

Styles of puppetry.

Think about the list of puppets above and you are immediately exposed to different styles of puppetry such as hand puppets and string puppets but the world of puppetry is much broader. I’ll briefly describe several different styles.

Sock and Human-arm puppets.

A sock puppet is, quite simply, the accurate description of a sock or sock-like garment worn over the puppeteer’s arm. The puppeteer keeps their hand between the heel and toe and uses their thumb as the jaw.

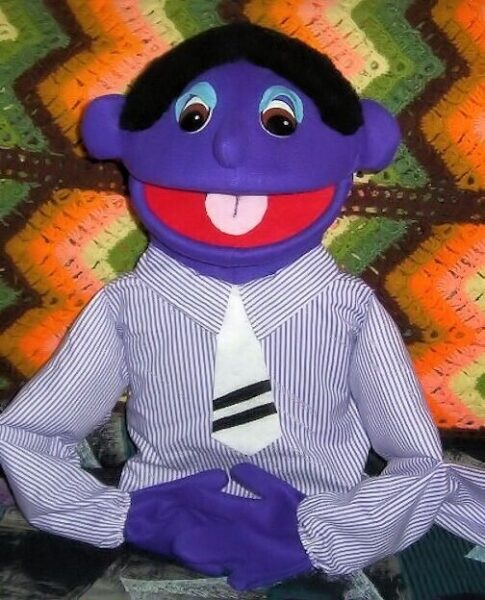

Human-arm puppets can be controlled by one or two puppeteers. When two puppeteers are working in conjunction, one controls the head and mouth while the other manipulates the arms.

[Photo from Ebay].

Articulated hand puppets.

The construction of this type of puppet allows the performer’s arm and hand to produce a wide range of expression and gestures. Perhaps the most famous recent incarnation of these is Kermit the Frog.

[Photo from Wikipedia.]

Marottes.

Marottes are puppets that generally feature only a head or body placed on a stick. Some might have one moving arm or a mouth that can open. Those having the latter enable dialogue to be presented realistically as being spoken by the character and avoids requiring additional movements to highlight speech by the puppeteer. Think of the court jester’s scepter.

Marionettes.

From the French word meaning “little Mary”, a marionette is a puppet controlled from above by strings. (Puppet itself derives from the Latin pupilla meaning little girl. That then found its way into French as popette which itself was a diminutive of popee – “doll”, and finally into English as popet or poppet.)

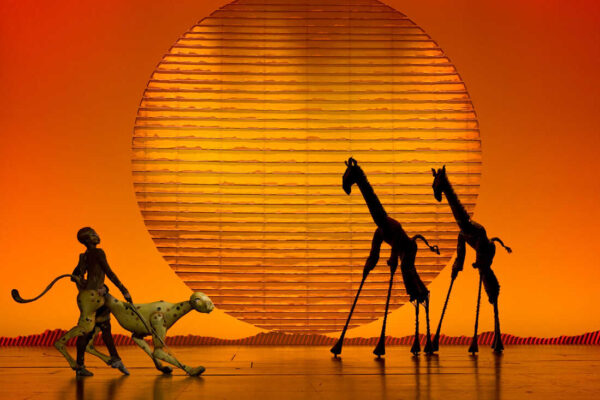

Body puppets aka Carnival puppets.

These human-sized or sometimes larger-than-life sized gigantic puppets are used in street spectacles or in large-scale theater productions.

While in the film “Circle of Life” is sung by a voice off-screen, Rafiki takes on the opening number in The Lion King musical.

[Photo from NPR.org].

Shadow puppetry.

In shadow puppetry, silhouetted figures are illuminated with a light source and manipulated by the puppeteers, producing shadows that the audience can see and from which they follow a performance and story. According to the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, “shadow puppetry originated in China over 2000 years ago during the Han Dynasty (140 – 87 BCE). ” and it quickly spread to other parts of the continent particularly India which adopted many different types of puppetry. UNESCO has deemed shadow puppetry an Intangible Cultural Heritage of China.

Bunraku.

Bunraku puppetry arose in Japan in the early 18th century. It’s performed using half life-sized wooden puppets manipulated by a principal operator and two assistants. All the puppeteers are dressed in black so, while they can be seen by the audience, they are accepted as invisible. The story has a single narrator who is accompanied by music played on the shamisen. It, too, is a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

[Photo from TradtionalKyoto.com].

So where does Portugal fit in with all of this?

No one can be certain when the earliest puppet shows appeared in Portugal but history shows that throughout the Middle Ages, puppeteers were often regarded with suspicion and fear and their art associated with black magic and devil worship. It’s thus reasonable to assume that the earliest puppet shows happened after the Council of Trent (1545-1563) when the Church began using puppet shows to support and spread the faith.

This coincided with the start of the Renaissance and, with the Portuguese age of exploration well under way, reports of puppet shows from China such as that written by the monk Gaspar Cruz in his Tratado das cousas da China (1569) or The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires about his three year journey from 1512-1515 probably contributed to the birth of a tradition of puppetry in Portugal.

Gaspar Cruz used the word bonifrate to describe what he saw from itinerant puppeteers in China – generally considered as the oldest and purest of the many Portuguese puppetry terms – that include marioneta, títere, bonecro, fantoche, and roberto. Thus, in much the same manner that the Portuguese were cross-pollinating both global cuisine as well as their own, they were also bringing these forms back to their homeland.

By the 18th century, puppet shows were quite popular and among those responsible for elevating the art was António José da Silva – a child of conversos. He was born in Brazil but his family returned to Portugal to escape religious persecution.

Called “the Jew”, da Silva wrote joco-sérias (humorous-serious) operas for puppets that blended literature, music, and baroque machinery with puppets while simultaneously transforming his characters from the stereotypes usually seen in puppetry at the time into psychologically complex characters.

His work often presented a satirical look at society perhaps laying a foundation for much of the subversive puppetry that followed. Ironically, da Silva, the child of conversos fleeing Brazilian religious persecution, was executed by the Inquisition at age 34 in 1739.

In the 19th century, a puppet theater using primarily glove puppets resided for a time in the Teatro Pinturesco e Mechanico. It’s thought that the origin of the word robertos arose as a shorthand reference to the theater’s director Roberto Xavier de Mattos. From this arose the touring companies that passed the art familially from generation to generation and who entertained the country well into the 20th century.

If you’re interested in exploring puppetry in more depth, you can do so at the website of the World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts. Otherwise, you can look at the few photos I took here or take a brief museum tour by watching the video below.

Fantastic read!! I definitely liked every bit of it and I have you book-marked to see new things on your site.

Hi there! I love puppets and could have sworn I’ve been to this

blog before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me.

Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I found it. I’ll be checking back often looking for the puppets.

Awesome post.

Thanks.