Sarajevo: City of Contrasts :

As this series demonstrates, I’m fortunate enough to have traveled extensively although I know there’s much more of the world I want to see. I’m frequently asked a question along the lines of, “What’s your favorite place to have visited?” My standard answer, “I find something to like about everyplace I travel,” is one that combines a grain of truth with a kernel of equivocation.

It should go without saying that I like some places better than others and some places touch me emotionally more than others. If pressed, I’d admit that one of those latter places is Sarajevo. Those of you who are following my travels chronologically and reading about each city’s Olympic Games will have read about the Games in Lillehammer and the last of the Lillehammer Tales provided some insight about my attraction to Sarajevo.

The title of my initial post about the city matches (and is linked in) this section’s header. In it, I wrote,

I’ve called Sarajevo a city of contrasts not because of the juxtaposition of old and new such as the remains of a 16th century inn excavated mere meters from our newly renovated hotel; nor because the city has always had a reputation for religious tolerance with a mosque, Catholic and Orthodox Churches and a synagogue all nestled in close proximity to one another; nor because it bills itself as

– where east meets west. For me, Sarajevo is a city of contrasts because it is at once among the most heartbreaking and heartwarming places you or I or anyone will ever visit.

The city has a long and often painful history. It’s likely best known for its place in three major historical moments – the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1918 that lit the final fuse and ignited World War I, hosting the winter Olympics in 1984, and suffering the four-year siege by Serbian paramilitary forces and the JNA from 1991-1995. Scars and reminders of that war are ubiquitous, indeed, almost omnipresent throughout Sarajevo but still the city crackles with vibrancy and life. We met people who were subject to horror and unimaginable deprivation but who today live in tolerance and with a measure of joy. In my memory, Sarajevo and its citizens will stand like monuments to the resilience of the human spirit.

I hope to recapture some of those feelings here but I wrote more than 11,000 words on my initial visit and distilling those posts to something close to the 1,500 word limit I’ve set for this iteration proved impossible. Thus, I’ll include two posts about my visit to Sarajevo and you should, dear reader, take that as a sign of my deep and abiding affection for the people and the place.

Three pieces of history.

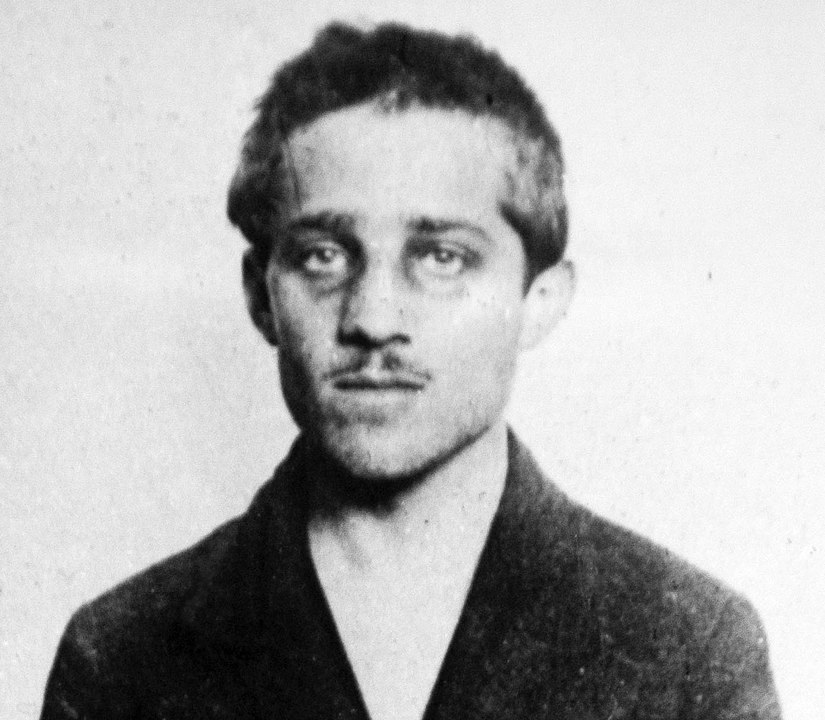

For those of us in the west who have any familiarity with Sarajevo it likely arises from one of the three major historical events I mentioned in my original post. The first would be the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, on 28 June 1914 by a Serbian nationalist named Gavrilo Princip that some historians say triggered the onset of the First World War – a claim that dramatically oversimplifies the events of the time.

[Photo of Gavrilo Princip from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

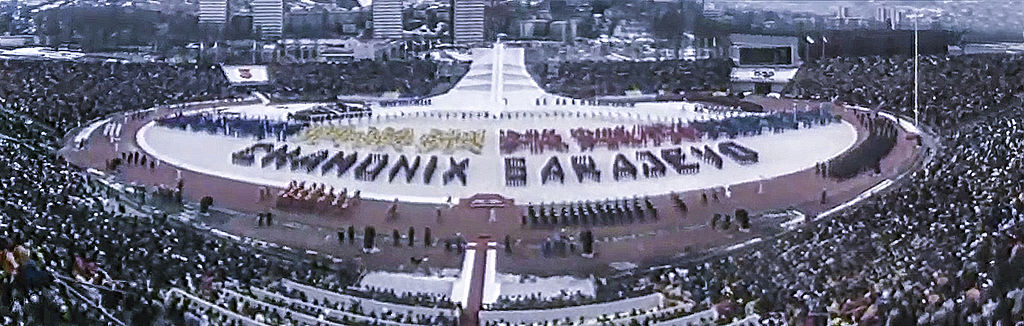

The second would be the reason for its inclusion in this series when, in 1984, as a republic in the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Sarajevo became the first city in a socialist state to host the Olympic Games.

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons By BiHVolim CC-BY-SA 4.0.]

The third, and most devastating of the three, is the Siege of Sarajevo. The daily shelling and sniper attacks by Serbian paramilitary and Yugoslav People’s Army forces began on 5 April 1992 and lasted for 1,425 days. This siege, the longest in modern warfare, finally ended on 29 February 1996. Many scars from this war remained present and visible

when I visited Sarajevo in 2016 but the city teemed with life affirming energy. Although many of the people I met, like their city, still bore physical and psychological reminders of the war, no one seemed to be weighed down by pessimism or anger but instead chose to embody the city’s renowned spirit of tolerance that had its seeds sown in the 15th century.

The early days.

The Balkans were one of the conquered territories during the westward expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. Although people had been living for millennia in the area that is now Sarajevo the official date of the city’s founding is usually given as 1461 under the Ottoman governor Isa-Beg Ishaković.

While the Ottomans could be ruthless in their acquisition of territory, once they had conquered a place they were generally quite cross-culturally tolerant. This proved to be a boon to one group of migrants to Sarajevo near the end of the 15th century – Jews expelled from Spain. Some fragmentary documents indicate the presence of a synagogue as early as 1491 so those arriving after the 1492 Inquisition and expulsions would have found a least a small community already there.

Gazi Husrev-Beg, the successor to Isa-Beg Ishaković, was, perhaps, the most important person in the early history of the city.

[Painting of Gazi Husrev-Beg from islamosfera.ru.]

When a fire destroyed the synagogue, Husrev-Beg not only permitted its reconstruction, he funded it in large part. But a rebuilt synagogue would be far from his only legacy. He oversaw the construction of a maktab and a medresa (primary and secondary schools), a hammam (public bath), an imare (a place that served the poor), a library, one of the first water supply systems in Europe, and, of course, the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque. After completing the mosque, he oversaw the reconstruction of the old Eastern Orthodox church near his mosque.

The baščaršija or old market expanded and flourished under Husrev-Beg. It became and remains the centerpiece of the old city.

At its peak, this marketplace stretched for more than six kilometers, hosted more than 77,000 merchants, and had more than 700 operational crafts regularly conducting business here. The market was open five days a week – closing on Friday and Saturday for the respective Muslim and Jewish Sabbaths – and it was a space where Jews, Africans, Asians, and Moors traded as freely as anyone else. The photo above is a model of the baščaršija at its peak that I took during a visit to the Brusa Bezistan Museum.

I’ve included this history to give you some understanding that Sarajevo has been a city of tolerant coexistence for centuries and to provide a little support to some of the comments made by the Bosnian bobsleigh team that competed in Lillehammer.

I have much more to say about Sarajevo and my visit there and will continue it in the next chapter.