The Railroad Story.

Fueled by the California Gold Rush of 1849, the idea for a transcontinental railroad took hold of the American imagination and body politic. Even from the beginning, several problems stood in the way of this dream – principal among them was the problem of finding a route through the terrain of the West, particularly the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

In 1860, the railroad engineer Theodore Judah uncovered a path through the Sierras using the infamous Donner Pass. (For those interested, Michael Wallis’ book The Best Land Under Heaven provides a fascinating detailed account of the Donner Party and their descendants.) Soon thereafter, Judah formed the Central Pacific Railroad and went to the federal government seeking financing for a transcontinental link.

Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862 providing land and financing to the Central Pacific and a second company, the Union Pacific, to construct a Western line that would connect with the existing Eastern lines. Central Pacific began construction in Sacramento and moved east, while Union Pacific began in Council Bluffs, Iowa and moved west.

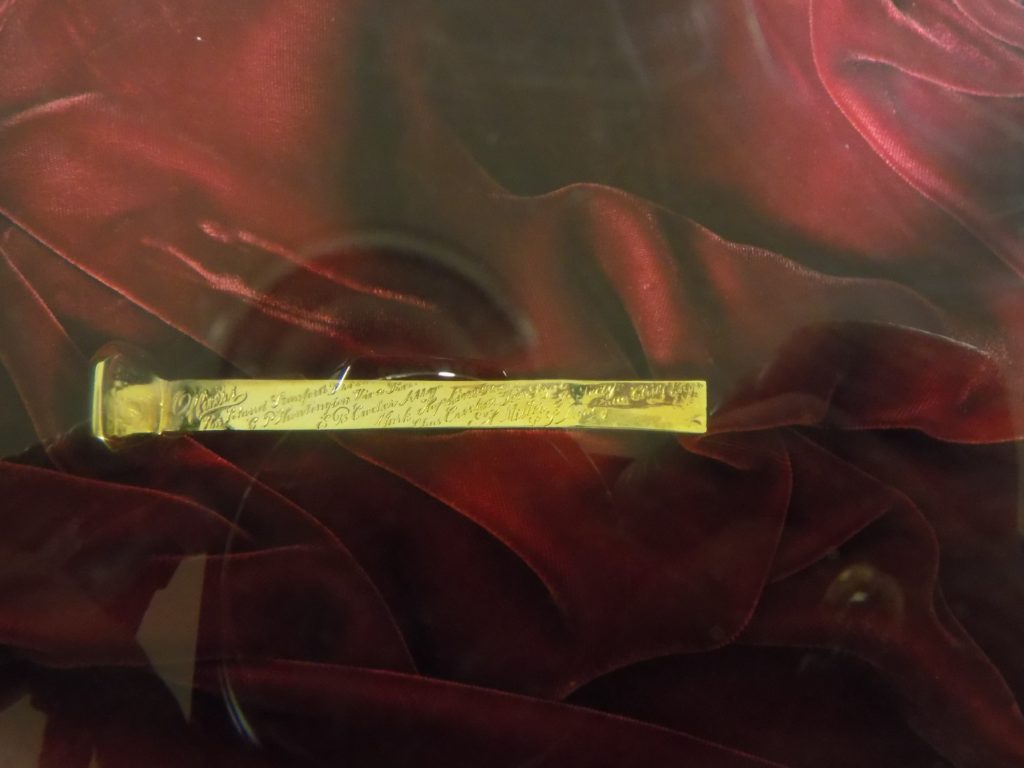

The lines met on 10 May 1869, with great ceremony at Promontory, Utah. California Governor Leland Stanford was appointed to drive the ceremonial golden spike. However, Stanford failed to hit the spike on his first attempt, apparently creating some hilarity among the railroad workers at the scene. According to some reports, the abundant and free flowing champagne intensified their mockery. Stanford found his target on the second try and for the first time in American history, railways linked together east and west.

The National Park Service maintains the Golden Spike National Historic Site at Promontory about 90 miles north and west of Salt Lake City. Before I entered the DUP Museum, a stop at Promontory remained on my day’s itinerary though by a rather tenuous thread. (Remember I’d heard some news Thursday night that had me considering changing my Friday plans.) In addition to the photos, paintings and narratives about the event, the museum also had this item (the actual golden spike) that unraveled that thread.

The Jim Bridger Story.

Another display on the museum’s ground floor was a small case of items belonging to Jim Bridger. I didn’t find the items themselves particularly interesting but his name was vaguely familiar and the display’s colorful description of Bridger provided in the case intrigued me. Of course, I looked him up. And, it turns out, he’s quite a fascinating character.

Apparently, Bridger was well known as a trapper, scout, and guide in the west through the middle third of the 19th century. Born in 1804 in Richmond, Virginia, he gained a measure of fame at a young age when, in 1824 or 1825, he became the first Euro-American to see the Great Salt Lake. It was so salty that he thought it was an arm of the Pacific Ocean.

The previous year, as part of General William Ashley’s Upper Missouri River Expedition, Bridger was one of the men involved in what became known as the Hugh Glass incident or ordeal. I won’t detail it but the event received a dramatic film treatment in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film The Revenant with Leonardo DiCaprio as Hugh Glass (with Oscars for both of them) and Will Poulter as Bridger.

However, Bridger had another skill that was unique among those generally rough men who served as scouts and guides in the west – He was a polyglot. Â Not only could he converse in French and Spanish, but he also learned several Native American languages.

The latter may have served him well when in 1835 he married a woman from the Flathead Indian tribe with whom he had three children. After her death in 1846, he married the daughter of a Shoshone chief, who died in childbirth three years later. In 1850 he married Shoshone Chief Washakie’s daughter, with whom he had two more children. He sent some of the children back east to be educated.

In 1850, while exploring for an alternative overland route to what was known as the South Pass, he found what would eventually be known as Bridger’s Pass, which shortened the Oregon Trail by 61 miles. Bridger’s Pass would eventually become the route used by Interstate 80 as it crosses southern Wyoming, Utah, and northern Nevada before turning south toward its terminus in San Francisco.

There’s more to come from my day in and around Salt Lake City so stay tuned. You can look at a few pictures while you’re waiting.