Oh, Philo, Come on before we go.

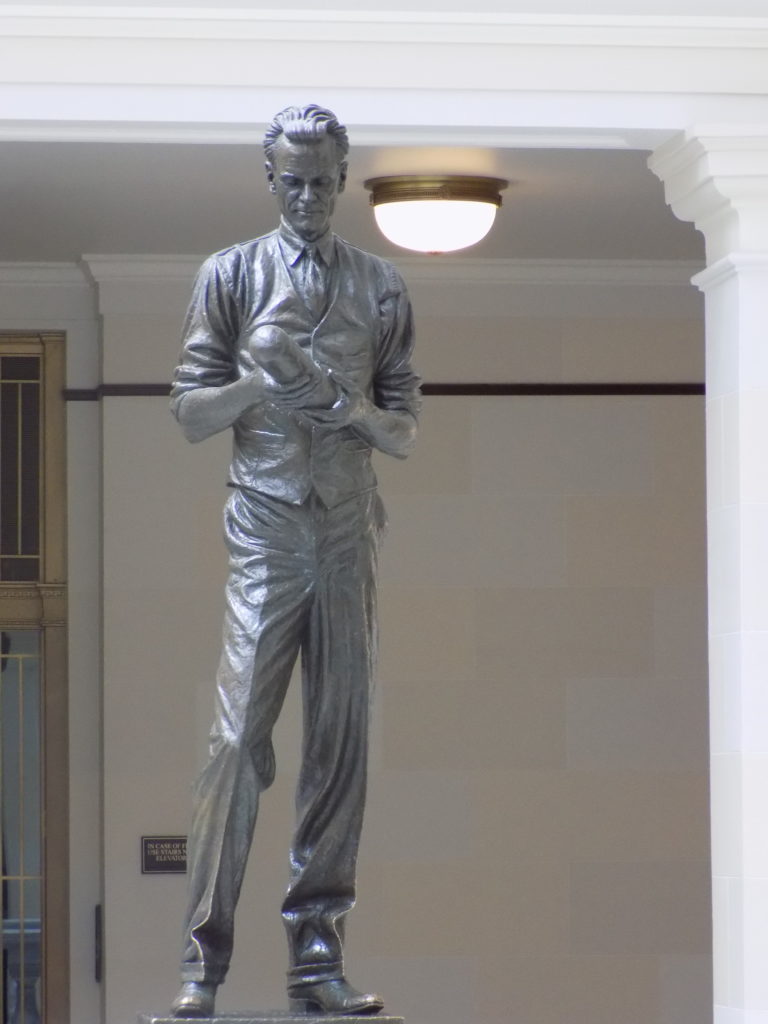

Hey, I’m in Utah. Don’t begrudge me another Footloose reference even if it’s a bit twisted. The reason I went to the Capitol building was to take a picture of this statue:

Why this statue? I’ll answer a question with a question. Do you now or have you ever watched television? If you answered yes, then you can thank (or curse) Philo T Farnsworth, the inventor of all-electronic television and the man depicted by this statue. (Some electro-mechanical systems existed before Farnsworth’s all-electronic version.) Yes, the inventor of television is a son of Utah.

Farnsworth was born in 1906 in a log cabin (really!) built by his grandfather near Beaver, Utah. He was a precocious and prodigious inventor who, as a teenager, converted his family’s home appliances to electric power, won a national contest with his original invention of a tamper-proof lock and, at age 14, sketched out an idea for a vacuum tube that would eventually lead him to the invention of television. It’s that very tube, called the “image dissector” that he’s holding in the statue.

On 7 September 1927, in a laboratory in San Francisco, that image dissector tube transmitted its first image – a straight line – to a receiver in another room. In 1929, Farnsworth transmitted the first live human images from his system including one of his wife, Pem.

Farnsworth didn’t live an untroubled life, though. And those troubles began in 1931 when he refused to sell his patents to David Sarnoff at RCA. This began more than a decade of lawsuits based in part on those pre-existing electromechanical systems and on some drawings made by Vladimir Zworykin (who had filed for patents as early as 1923 but who had never developed a working system from his design). The deeper pockets and influence of RCA won many of those court battles one of which overturned a 1934 U S Patent Office decision that had forced Sarnoff to pay royalties to Farnsworth.

But Farnsworth applied his inventiveness to more than simply television. Over his lifetime, he held more than 300 patents that contributed to the development of radar, infra-red night vision devices, the electron microscope, the baby incubator, the gastroscope, and helped develop cold cathode ray tubes (CRT) that became widespread in televisions and computer monitors.

In 1957, Farnsworth made a fascinating appearance on the television show “I’ve Got a Secret.”

It’s fascinating not so much for stumping the panel (or for seeing a cigarette brand sponsoring the show) but for the conversation he has with Garry Moore after the game. In this segment he talks about cold fusion (and one of his inventions, the “fusor” is still used in explorations of developing cold fusion as a power source) and notions of HDTV!

(On 2 July 1864, Congress enacted a law authorizing the President

“to invite each and all the States to provide and furnish statues, in marble or bronze, not exceeding two in number for each State, of deceased persons who have been citizens thereof, and illustrious for their historic renown or for distinguished civic or military services…”

in the U S Capitol.

At first, all the statues were placed in Statuary Hall as the statute required. Over time, the hall became too crowded and in 1933 Congress amended the law to allow their placement throughout the Capitol. As late as 1985, Utah had only one statue in the Capitol. A group of students and teachers from Ridgemont Elementary School in Salt Lake City lobbied the state legislature to honor Farnsworth by having his statue join Brigham Young to fulfill Utah’s quota. Now you don’t need to go to Utah to see the statue above. You can also see it in the U U S Capitol Visitor’s Center.)

Though he did much of his work away from his home state, Farnsworth returned to Utah in 1967 and died four years later of complications from pneumonia. In 1999, Farnsworth was one of the 20 Scientists and Thinkers included on Time Magazine’s 100 Persons of the Century list.

O Pioneers!

The only way to make sense of the header for this section is if you know that I’m about to visit the Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum (formally the Pioneer Memorial Museum), that this blog may sometimes seem as long as a Willa Cather novel, or as a sly reference to my time in Croatia.

The concept of the pioneer is important in the Mormon world view. Without question, the LDS Church was a persecuted minority in the United States. I touched on the Mormon experience in their settlement at Nauvoo in a previously linked entry. Beginning in 1846, under great pressure, most Mormons were forced to leave Nauvoo and begin what’s called in LDS history, the Trek West.

After spending the winter in Iowa (with a few advance teams having gone ahead to Nebraska), the first company left with Brigham Young as their leader in the spring of 1847. That first group arrived in Salt Lake Valley on 24 July 1847 – nearly 1,300 miles from Nauvoo. Between 1847 and 1869, more than 70,000 people traveling by wagon, horse, and even pushing handcarts crossed the plains and mountains to get to Utah.

In leading the LDS believers to a place where they could be free from religious suspicion and persecution, the vision and determination of Brigham Young likely played a major role in the success of this migration. Consider that at this time, these travelers typically covered just 15 to 20 miles per day.

Young organized the people into companies of hundreds, fifties, and tens, each with a captain. Individuals traveling alone, especially women without husbands and children without fathers were adopted into other families for the journey. One pioneer wrote, “Everyone had an assignment, everyone felt personally essential to the company’s higher purpose. Taking everything into account, the Pioneer Company was probably the best-supplied, best-armed, and most trail-experienced group to go west up till then. Even so, being led by a determined man armed with a dream probably made all the difference.” The success of their trek is self-evident.

In 1901, a woman named Annie Taylor Hyde gathered a meeting of 46 women, all descended from pioneers and laid the foundation for an organization that became the International Society Daughters Utah Pioneers (ISDUP) whose goal was

to perpetuate the names and achievements of the men, women and children who were the pioneers in founding this commonwealth by preserving old landmarks, marking historical places, collecting artifacts and histories, establishing a library of historical matter and securing manuscripts, photographs, maps, and all such data as shall aid in perfecting a record of the Utah pioneers.

(From ISDUP).

It is to their museum that you are now accompanying me. But first, a step back. On my way to the Capitol, at the intersection of State and South Temple Streets, I drove under this structure

that I later learned is called the Eagle Gate. At one time, a gate at or near this spot marked the entrance to Brigham Young’s estate at the mouth of City Creek Canyon and near where the pioneers homesteaded that first summer in 1847. A different gate that served as the entrance to a toll road was installed at some later date. Today, a bronze plaque nearby says Eagle Gate has come to represent both Brigham Young and the pioneer spirit. I was surprised, then, when one of the first things I saw in the DUP Museum was this:

It’s the original eagle from the Eagle Gate.

This museum’s website claims that it is

“noted as the world’s largest collection of artifacts on one particular subject, and features displays and collections of memorabilia from the time the earliest settlers entered the Valley of the Great Salt Lake until the joining of the railroads at a location known as Promontory Point, Utah, on May 10, 1869.”

I can’t speak to the claims about the size of the collection but it is exceptionally eclectic. The first floor focuses primarily on Brigham Young and his first counselor, Heber C Kimball. Elsewhere the collection includes handwork fashions, chinaware, and medicine (including a jar of extracted teeth) to go along with a display of rattles from rattlesnakes. And of course, no visit to the museum would be complete without stopping to see

the delightful two-headed lamb.

the delightful two-headed lamb.

An adjoining building displays an original pioneer wagon, surreys, sleighs, handcarts, bicycles, a blacksmith shop, and a mule drawn street car but it was the basement with its railroad display and a small case of items that belonged to Jim Bridger that drew most of my attention. I’ll take an extended look at it in the next, newly shortened post.