A few words about Vienna’s public transportation system.

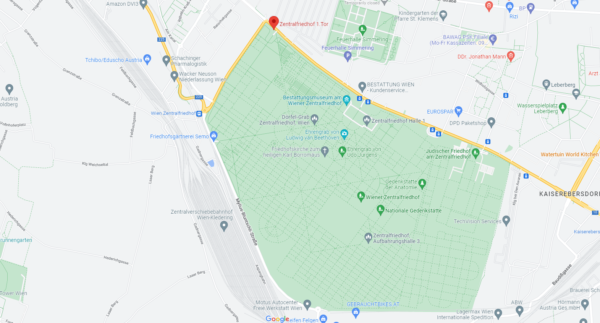

Although Saint Marx Cemetery is four kilometers from Saint Setphen’s Cathedral, it’s less than halfway to the somewhat ironically named Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery). Fortunately, it’s more or less a straight line between the two so I simply had to get back on the 71 tram into the 11th district called Simmering. The cemetery itself is so large the tram stops at its four gates. Wanting to have some time to walk through its outer reaches, I hopped off at Gate One (the pin at the top center of this look from Google Maps).

Public transportation in Vienna is entirely on the honor system. You never have to pay a euro if you dare. But, if you’re caught without a valid ticket by one of the plain clothes ticket inspectors, you’re immediately entitled to a free ride to the nearest police station where you’ll have to pay a 105 euro fine. It’s a big gamble since a 1 day pass costs a mere €5.80. I used the trams and Metro frequently during my stay and found it easy and convenient.

On to Zentralfriedhof.

When the cemetery opened on 1 November 1874, it wasn’t immediately well received. Many Catholics, in particular, had an issue with its interdenominational character. The location, more than nine kilometers from Saint Stephen’s Cathedral in the heart of Vienna generated more resistance to its usage than the city planners hoped.

Those of you who followed my trip to Paris might recall that when the Cemetery of the East opened in 1804, it faced similar problems and at the end of its first year held a mere 13 graves. The developers took several steps to make it more appealing. First, they gave it a new name – Père Lachaise. Then they began to relocate famous people – starting with Molière in 1804 and adding the ill-fated lovers Pierre Abélard and Héloïse d’Argenteuil in 1817.

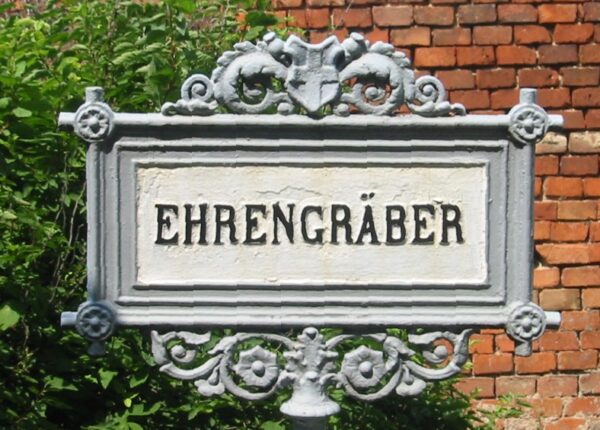

With 15 people buried there on its first day, Vienna’s Central Cemetery wasn’t quite as bare as Père Lachaise but it still struggled to attract sufficient people not only to meet the projected needs of a rapidly growing metropolis but to make it a viable proposition. Taking a similar approach to that used in Paris, they developed the

Ehrengräber or honor grave. The plan worked. Today, the cemetery has more than 330,000 burial sites and a “population” of more than 3,000,000. In 2019, Vienna’s living population was 1,900,000 – less than two-thirds that of the cemetery. Also, the Ehrengräber are a major reason that I and most people ride tram 71 to visit the Zentralfriedhof.

Hah! You’ve been caught.

If you’re thinking this admission undermines the reasons I gave regarding my fascination with cemeteries in the post about the Cimetério de Prazeres – where I talked about cemeteries as places to find art, history, cultural values and ethos, or simply having a spot for quiet contemplation and that since I just admitted going to Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof to see the Ehrengräber, I’ve somehow exposed the true reason, I’d suggest you reread that passage. I began by noting, “…you need to know that while I will often visit a cemetery to see the grave of someone I admire it’s not for this reason alone.” It’s an all of the above situation.

So it was, after a westward walk along the northern wall, that I set off to Group 32A – the musicians section of the Ehrengräber. Here, in close proximity you have

Beethoven on the left, the relocated monument to Mozart in the center, and the grave of Franz Schubert on the right. Just to Schubert’s right are Johann Strauss II and Johannes Brahms. But, of course, these aren’t the only famous musicians and composers in Group 32A let alone the entire cemetery.

Unlike Beethoven and Schubert, Brahms (1897) and Strauss (1899) were both initially interred not only in Zentralfriedhof but in Group 32A. Beethoven died on 26 March 1827 and within a few days was buried in Währinger Ortsfriedhof on the opposite side of central Vienna. His coffin was first exhumed in 1863 when authorities made repairs to the site. He was reburied in a metal coffin. That cemetery closed in 1873 eventually becoming a park. In 1888 authorities decided to move him to Group 32A.

Schubert’s body followed a similar path. Franz Schubert died on 19 November 1828 less than two years after Beethoven and a few months shy of his 32nd birth anniversary. His body was buried in Währinger Ortsfriedhof next to Beethoven. Two stories are told about how this came to be. One is that Schubert made a deathbed request to be interred by Beethoven. The other is that while attending Beethoven’s funeral service and even helping carry the coffin, he expressed a wish to his friends that he be remembered as fervently and that he be buried next to the great composer. Like Beethoven, Schubert was exhumed in 1863 and again in 1888 when he was reburied again in the plot adjacent to his great inspiration.

Peter’s Principle.

I think it’s been relatively well established that I’m not always shy about being intrusive, can be overly pedantic, and have something of a motor mouth so it should come as no surprise when I tell you that I saw a chap looking at the Mozart memorial and immediately had to disabuse him of the notion that this was Mozart’s grave.

Apparently, I wasn’t the only buttinsky in the cemetery that day as we were soon joined by a chap named Peter. Peter, I learned later, was born in Prague, moved to the U S as an adolescent, was now living again in Prague, and happened to be visiting Vienna. We began chatting as fellow music lovers and I showed him the list of graves I hoped to visit while in that particular cemetery. We bonded a bit further over our efforts to locate the graves of Christoph Willibald Gluck, whose reforms to opera composition undoubtedly influenced Mozart,

and Arnold Schönberg who developed the most influential dodecaphonic compositional method.

(Interestingly, Schönberg is buried in Group 32C not far from the other musicians but not quite with them, either. If you enlarge the map at the top of this post, you’ll see that there’s also a specific Judischer Friedhof or Jewish section. Schönberg found his place in neither.)

Peter guided me to Hedy Lamarr’s grave where the steel rods and balls form a pixelated portrait of the actress and inventor while also honoring the radio signaling invention she patented in 1941. The small marker noting her dates and places of birth and death also reads,

“Films have a certain place in a certain time period. Technology is forever.”

(Lamarr invented a technology called frequency hopping that allowed encryption for torpedo guidance systems during World War II. These techniques became the basis for modern wireless communications such as Bluetooth and Wi-Fi.)

Before Peter left to catch his transport back to Prague, he provided me his cell phone and encouraged me to call when I reached there. After he left, I wandered about the cemetery for some time longer and you can see the results here.

Before I left Zentralfriedhof, I had to find one last gravesite – that of Antonio Salieri – about whom I’ll have more to say in a later post. Somewhat sadly, while his body was moved to Zentralfriedhof from its original internment at Matzleinsdorfer Friedhof he’s not buried in Group 32A with the other musical giants or even in 32C with Schönberg. Salieri’s grave is past the Jewish section along the western wall beyond. You’ll find his modest grave between the painter Joseph Klieber and the physician Franz von Wirer.

Lunch. And more about Vienna’s public transportation system.

One of the bonuses of being able to purchase a day pass is that public transit becomes something like the hop-on hop-off tour buses. Thus, I had no reservations about hopping off the 71 tram on my way back to the city center to explore the Simmering neighborhood and to find a place to eat lunch.

As is often the case, one of the other features of visiting these large old urban cemeteries is that it takes you into and through parts of a city that you likely won’t experience otherwise. This was certainly the case with my visits to both Prazeres and Zentralfriedhof. If central Vienna is the heart of the city pulsing with theatre, music, museums, and the like then a place like Simmering feels like the city’s lungs. It’s where the people who animate the city, provide its toil, but can’t afford the high-end tourist shopping live and work.

True, I didn’t stray too far off Hauptstraße and had lunch at the Simmeringer Landbier where I had “Geröstete knödel mit Ei und grünem salat” – Roasted dumplings with a side salad with a .3 liter Pilsner Urquell (a Czech beer). After lunch I was able to comfortably hop back on the 71 at Braunhubergasse confident I’d seen a side of Vienna far different from the Schönbrun Palace. Others might not be so but I certainly was the happier for it.