Mi Teleférico.

After our visit to the witches market, we spent much of the rest of the day soaring over La Paz and into and out of El Alto on the wings of the area’s mass transit system Mi Teleférico.

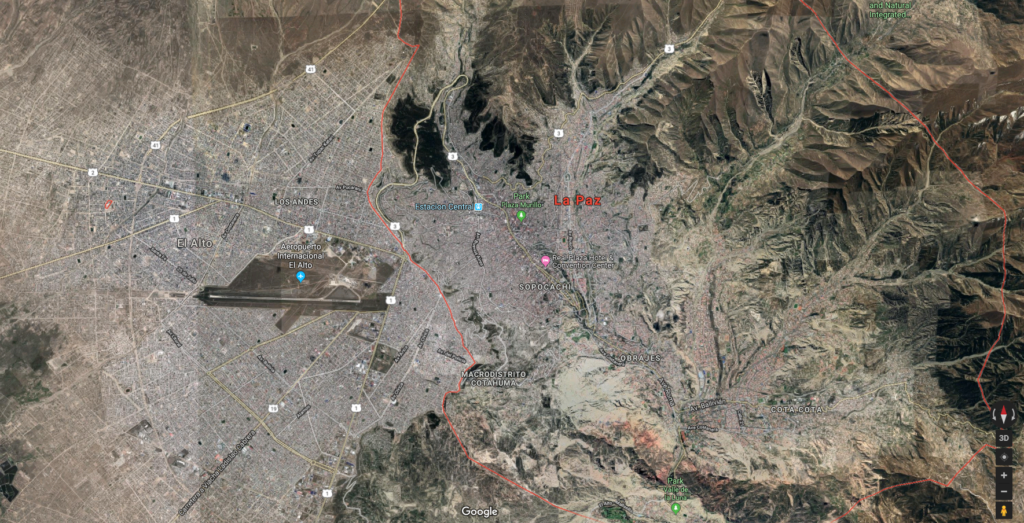

The system is primarily meant to connect the neighboring cities of La Paz and El Alto – the second and third largest cities in Bolivia – though looking at this satellite image, while you can easily spot the airport, you might be hard pressed to see where one city ends and the other begins.

[Satellite image of La Paz and El Alto from Google maps.]

However, as the photo above the layered map view shows (and as I mentioned on our arrival at the airport) there is a substantial difference in the elevation of the cities. Although the routes by car are so circuitous that they can be two to three times longer, if one was to walk from the airport to the hotel where our group stayed, it’s a mere four kilometers. The descent, though, is on the order of 500 meters.

Noting the difference between walking and driving demonstrates one of the challenges these conjoined cities face. El Alto has, perhaps, the fastest growing population of any of Bolivia’s cities and it serves as a residential landing spot for many people who work in La Paz. With population growth comes traffic growth and even in places with a well-established and well-designed infrastructure of roads and highways substantial traffic congestion becomes endemic.

To emphasize the point, I’ll return to one of my surreptitious pictures of a cholita. Rather than looking at her,

shift your focus to this relatively typical La Paz street. Narrow, and not designed to accommodate large volumes of traffic, though it might be long-established, it would require a stretch of imagination to call it well-designed. The steep change in elevation between the two cities compounds the problem because roads connecting the two must be more serpentine than direct.

More than a quarter million people commute between El Alto and La Paz every day. So how does one alleviate congestion? The geography that demands circuitous routes combined with the narrow streets of La Paz and the slow traffic can make trams and buses as nearly impractical as any other vehicle. Thus, the solution becomes Mi Teleférico.

Built by the Austrian Doppekmayr Garaventa Group, Mi Teleférico is probably the largest aerial cable car system in the world. Construction began on the system’s first three lines (Green, Red, and Yellow – not coincidentally the colors of Bolivia’s flag) in July 2012 and opened less than two years later in May 2014. The combined length of the three lines was 10 kilometers and each line could carry up to 3,000 people per hour in the eight person cabins.

Since that initial phase, the system has added six additional lines and nearly another 16 kilometers in length including the Silver Line which opened just days before our arrival. In keeping with the vision of Bolivia as a plurinational multilingual state, each station has both a Spanish and Aymara name.

For Bolivians riding the system to ease congestion and expedite the passage between the two cities the cost of three Bolivianos (about 40 cents) is relatively affordable and it reduces their commuting time by as much as 40 minutes. For tourists, it’s an inexpensive way to see some astonishing views of the two cities. It requires a bit more than two hours to complete a circuit of all nine lines and costs less than four dollars. And, if you have a guide with you to point out the sites and answer questions, you not only enhance the experience but can learn how to use the system to visit sites on your own.

While it may be somewhat less apparent at street level, La Paz, and El Alto for that matter, (and as I would find in most large cities on this trip)

look to be perpetually under a sort of informal construction. La Paz sits in a canyon created by the Choqueyapu River and is surrounded by mountains. Now filled, the almost bowl-shaped depression leaves La Paz with little place to build but up the sides of those mountains. Some of the houses look so precariously situated that, for me, it evoked images of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

Sadly, a week or so before I published this post, a landslide collapsed 17 homes in La Paz according to this BBC report.

As you will see when I look at another recent Bolivian phenomenon – the development of the architectural style known as cholets – one of the norms of traditional Andean culture is to build up. Though not necessarily the case in a cholet, children often share living quarters with their parents. The first generation purchases land and establishes a homestead. As their children mature, look to marry, and start families of their own, they simply add a new floor above the original residence to accommodate the new generation. It’s a continual and ongoing process.

Back on the ground.

After completing our rides on Mi Teleférico we descended to central La Paz for a necessarily slow walking tour. Our first stop was Plaza Murillo – the location of the Bolivian government administrative buildings – and the square that once barred the cholitas from even walking through it. The plaza honors Pedro Domingo Murillo who is considered both a hero and martyr in Bolivia’s fight for independence that began in 1809 and lasted until 1825.

(Much to your relief, I’m sure, I could discover only a little biographical information about him and little of that seemed relevant to this post.)

The five of us had a brief discussion of the rather jarringly inappropriate look of the new government buildings President Morales was adding to the La Paz skyline and watched the pigeons flock around the schoolgirls in the square. When we’d had our fill of that, we moved on to the Museum of Musical Instruments (no photos). This small and curiously interesting museum’s collection is filled with indigenous instruments. According to the website LaPaz Life,

The museum’s seven rooms feature over 2000 percussion, string and wind instruments used throughout the different regions of Bolivia as well as a comprehensive collection of charangos; an Andean guitar-like instrument. What makes these instruments so unique are the peculiar materials they are made from such as turtle shells, toucan beak, goat heels and mules’ teeth.

On our way back toward the Witches Market and the neighborhood of our hotel, we passed this floral display showing that La Paz views itself

(Marvelous La Paz) much like Rio de Janeiro thinks of itself.

We still had most of the afternoon free. Jan and Jill wanted to do a little shopping so I decided I would set out on my own to visit an unusual museum I’d read about in preparation for visiting La Paz. In its own way it represents another reclamation project – one that’s still in progress and that has a long way to go. Still, it turned out to be quite the educational experience. More about that in the next few posts.