And now we return to our regularly scheduled programming.

Although he had won the competition, da Silva Costa’s original idea of Christ holding a cross in his right hand and the world in his left was sometimes ridiculed. People called it “Christ with a ball” and, as a result, the project became more collaborative. With da Silva Costa’s blessing, Brazilian artist Carlos Oswald modified the design to show the standing figure with outstretched arms – making Christ himself the cross – that we see today.

In da Silva Costa’s vision and religious fervor, the statue would face east. He wrote,

The statue of the divine savior shall be the first image to emerge from the obscurity in which the earth is plunged and to receive the salute of the star of the day which, after surrounding it with its radiant luminosity, shall build at sunset around its head a halo fit for the Man-God.

Meanwhile, he surveyed the city from a number of vantage points looking up at Corcovado and the radio tower that occupied the crest and realized that, for the statue to be visible from the city center, which was four kilometers away it would need to be enormous. In addition, if the new design held, to retain proportionality, it would need to be immensely strong or it wouldn’t support the massive extended arms.

With fund-raising still in process and some doubt regarding his own expertise in realizing his vision and Oswald’s design, da Costa Silva traveled to France in 1924 where he sought assistance from perhaps the leading engineer in this field, Albert Caquot. Caquot supported da Silva Costa’s notion that the only appropriate material for the statue would be reinforced concrete.

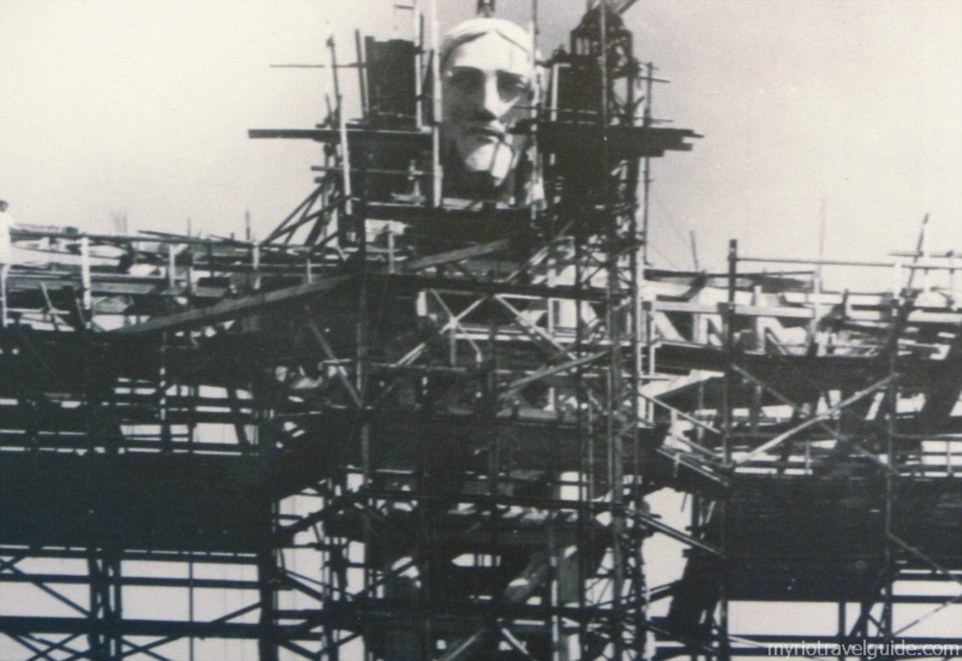

While in France, he took Oswald’s drawings to several sculptors proposing they render a four-meter-high scale model. The commission ultimately went to Paul Landowski who took Oswald’s fashionable art deco design and further stylized it with special attention to the figure’s head and hands. A Romanian sculptor, Gheorge Leonida, worked with Landowski on the look of the statue’s face. Here is Landowski working on the creation:.

Christ the Redeemer project- Christ-the-Redeemer-under-construction.jpg (Daily Mail Online).

Landowski produced these full-sized pieces of the head and hands in clay then shipped them to Brazil to be reproduced in concrete.

Much of the reported cost of $250,000 (or approximately $3,500,000 in today’s dollars) had been raised and with the sections transported by rail up the mountain, the statue was beginning to rise amidst the scaffolding. Still, da Costa Silva had one last challenge to overcome. He thought that concrete was too rough and crude to provide the statue’s finish. He later wrote, “We were marching towards the inevitable artistic failure, without being able to go back.”

One evening inspiration struck when da Silva Costa was walking by an arcade on the Champs-Élysées. There he saw a fountain covered in a silver mosaic. Of this he wrote,

By seeing how the small tiles covered all the curved profiles of the fountain, I was soon taken by the idea of using them on the image which I always had in my thoughts. Moving from the concept to the making of it took less than 24 hours. The next morning I went to a ceramic studio where I made the first samples.

[Photo of Christ the Redeemer under construction from Daily Mail Online.]

Ultimately, believing in the durability of the material, he selected a pale colored soapstone from quarries near Ouro Preto in the state of Minas Gerais some 400 kilometers north of Rio de Janeiro (and home to the gold and diamond discovery that drew early fortune hunters from much farther south). The stone was cut into small isosceles triangles, sown onto linen squares by volunteers, and attached to the sculpture. Although it could be little more than an urban legend, it’s been said that the volunteers – all of whom were women from parishes near Corcovado – wrote secret wishes and messages on the backs of the tiles.

The completed statue reaches a height of 38 meters. The statue itself is 30-meters-tall and the pedestal on which it stands adds another eight. Its open arms span 28 meters. On the day of its inauguration on 12 October 1931, Rio looked like this:

[Aerial photo of Rio in 1931 from Daily Mail Online.]

Today, in a similar view, Rio looks like this:

For more photos and a video click here.

Although the concept of the statue was seen by some as a way of reclaiming the city of Rio for Christianity, the Cariocas have never entirely shared da Costa Silva’s vision and viewed it in an exclusively religious light. Even one of the instigators of the project in the 1920s, described the completed work as “a monument to science, art and religion.” Today it’s seen as a symbol of Brazil as much as it is considered a religious and cultural symbol.

Carnaval in Rio, as Jill can attest, is filled with street parties an one of the most famous of these celebrations takes place in the neighborhood beneath Corcovado. The party is called Suvaco do Cristo or, in English, Christ’s Armpit. It’s almost expected that the dancers and drummers who weave their samba magic through the streets will be clad in something that bears the image of the statue standing above them.

Marcio Roiter, president of Brazil’s Art Deco Institute, sees Cristo Redentor as “somebody giving you a hug – welcoming you.”

Gilberto Gil seems to have shared that sentiment in his song Aquele Abraço.