Before the Sparkles a little history.

When it was built to be the entrance for the 1889 World’s Fair intended to celebrate the centennial of the 1789 Revolution, the Tour Eiffel (Eiffel Tower) was not greeted as the iconic symbol of Paris that it has become. Today, few if any, structures in the world are more immediately recognizable and, I’d dare say fewer still more closely associated with their location.

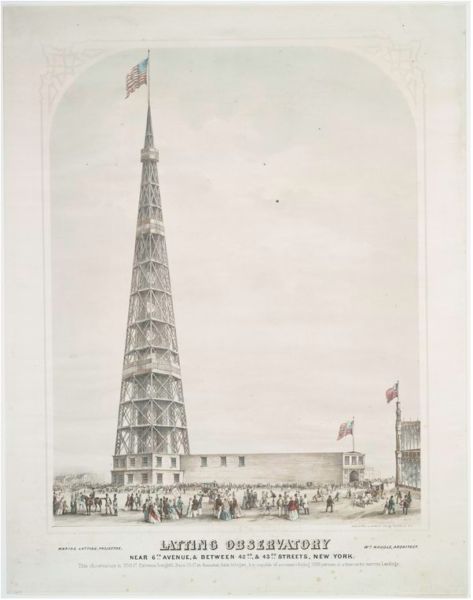

Rising 324 meters from a square base measuring 125 meters on each side, it remains, nearly 130 years after its construction, the tallest structure in Paris. It was, in fact, the tallest man-made structure in the world until the completion of the Chrysler building in New York City in 1930. Interestingly, Eiffel noted that a different NYC structure – the Latting Observatory a 96-meter-tall wooden tower built in New York for an 1853 exhibition – had inspired the design of his tower. (The Latting Observatory was destroyed an 1856 fire. It wasn’t rebuilt.)

[Image of Latting Observatory from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.

Two senior engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguie, who worked for his company -Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel – were the Tower’s principal designers. After receiving grudging approval from Eiffel for their design, the two engineers asked Stephen Sauvestre, the head of the company’s architectural department, to contribute to it. It was Sauvestre who added the distinctive arches at the tower’s base as well as a glass pavilion for the first level.

After winning a competition for his proposed tower to become the centerpiece of the exposition, Eiffel actually took substantial personal financial risk to move ahead with the project. Signing the contract as an individual rather than as a representative of his company, the French government awarded him 1,500,000 francs for its construction. The projected cost, however, was 6,500,000 francs.

In exchange for risking the remaining 5 million francs – about half of which was his own money – Eiffel received the rights to all the income the tower could generate both during the exposition and for the ensuing two decades. Ownership would then transfer to the city of Paris.

Work on the tower began on 28 January 1887. Even in its early design stages, it was somewhat controversial with its aesthetic adding fuel to a long-standing debate in France about the conflict between architecture and engineering. And it didn’t take long for some among the French elite to react.

Charles Garnier, a prominent architect of the time, formed and led the “Committee of Three Hundred” that included such other French eminences as Guy de Maupassant, Alexandre Dumas Fils, Charles Gounod, and Jules Massenet. They wrote a letter to the Commissioners for the exposition that was published in the Paris daily Le Temps. It read, in part,

We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection … of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower … To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years … we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.

But construction continued and by 20 March 1888 the first level was complete.

[Photo from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

A year later the main structural work was finished and on 31 March Eiffel led a delegation of the press and government officials to the top of the tower. Not all of them completed the ascent since the elevators weren’t yet operational. This was still the case when the public was granted access on 15 May 1889 some nine days after the exposition had opened.

Still, it was an immediate success. Even before the elevators were placed into service on 26 May, a reported 30,000 visitors paid 5 francs to climb the 1,710 steps to reach the top of the tower. Those choosing to stop at the first level paid only two francs and other visitors stopped at the second level for a three-franc admission. By the close of the expo on 31 October nearly 1,900,000 people had made the visit.

Many people expected the tower would be dismantled in 1909 when the ownership passed from Eiffel to the city of Paris as the original contract had stipulated. Obviously, that didn’t happen. In part this was due to the tower’s popularity with the general public and its usefulness in a number of scientific and commercial ventures.

In 1896, a fellow named Guglielmo Marconi patented a system of wireless telegraphy based on Hertzian waves. Today, we call that system radio. Thus, in the waning days of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, the Eiffel Tower gained some importance as a communication tool.

Within the next decade the tower had become so much the symbol of the city that the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who often wrote his poems as calligrams wrote this one in 1916 called

La Tour Eiffel that pokes less than gentle fun at the Germans.

The sparkles at last.

Here’s a myth some people might have about the Eiffel Tower: It’s so tall that it’s visible from anywhere in Paris. It isn’t. Now, here’s a not so well-kept secret about it: It’s illuminated every night. And here’s another: At the top of every hour the lights twinkle for five minutes.

Expecting that the set at Duc de Lombards would end around 21:00, Pat and I had talked about the best vantage point from which to see the show – perhaps a spot between the club in the first and our hotel in the 17th. Even in April, sunset in Paris is fairly late. (In fact, I snapped the photo of Duc de Lombards after the show.)

We’d ridden past the Arc de Triomphe (formally Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile) at least twice and I’d noticed people standing on its top so when we returned to our hotel from the concert at the American Church, I asked the concierge for the operating hours. He told us that it was open until 23:00 but that the last admission was at 22:00.

At the end of the set, we made our way downstairs, thank Fred and Jie for telling us about the show and were thanked in turn by Pete and Lynn Simpson – two fellow travelers whom I’d told about the show – then quickly hailed a cab to take us to the west end of the Champs-Élysées hoping to arrive in time to reach the top of the Arc.

Most people have to climb 284 stairs to ascend to the top of the Arc de Triomphe. There is an elevator (ascenseur) however, it’s available only by request and visitors must be accompanied by a guard to ride it. I don’t know if there are any rules but I assumed our grey haired pates might have been useful in gaining its use.

We made it with a few minutes to spare but as you will see from the photos, although it was about 21:45 when we arrived, it wasn’t quite fully dark – especially looking west.

By this time, though, the air temperature had dropped – I’d guess to about 10° – and the winds, which were much stronger at the top of the Arc than they were on the street, made it feel much colder. While Pat and I spent much of our time looking for a niche to provide a bit of shelter as we waited for the full show to begin, I did manage a picture or two looking south.

You’ll can visit my Google photo album to see more photos from the night and my windblown video of the full light show.

On our descent, we stopped to look at the eternal flame at the Tomb of the Unknowns at the base of the Arc. With the (moderately helpful) assistance of my phone’s navigation app, we walked back to the hotel in about 15 minutes bringing us to a chilly but delightful end to our first full day in France.

There will be more art and music tomorrow before we set sail toward Normandy but to learn about it, you’ll have to read the next post.