A plan of action.

Once he recovered, he adopted the stage name Robertson and returned to Paris where he would perform his first show on 23 January 1798. (Coincidentally, my father would be born on this day exactly 125 years later.) An innovative thinker, Robertson built on Kircher’s work and made technical improvements to his magic lantern that he eventually came to call a Fantoscope. He also developed an unmatched sense of theatricality.

His first, and for his purposes most important innovation, was to put his Fantoscope on wheels. This allowed him to create either a moving image or one that increased and decreased in size. He also added a diaphragm that allowed the user to regulate the amount of light passing through the device. Finally, he developed methods that allowed him to use multiple slides in a single projector.

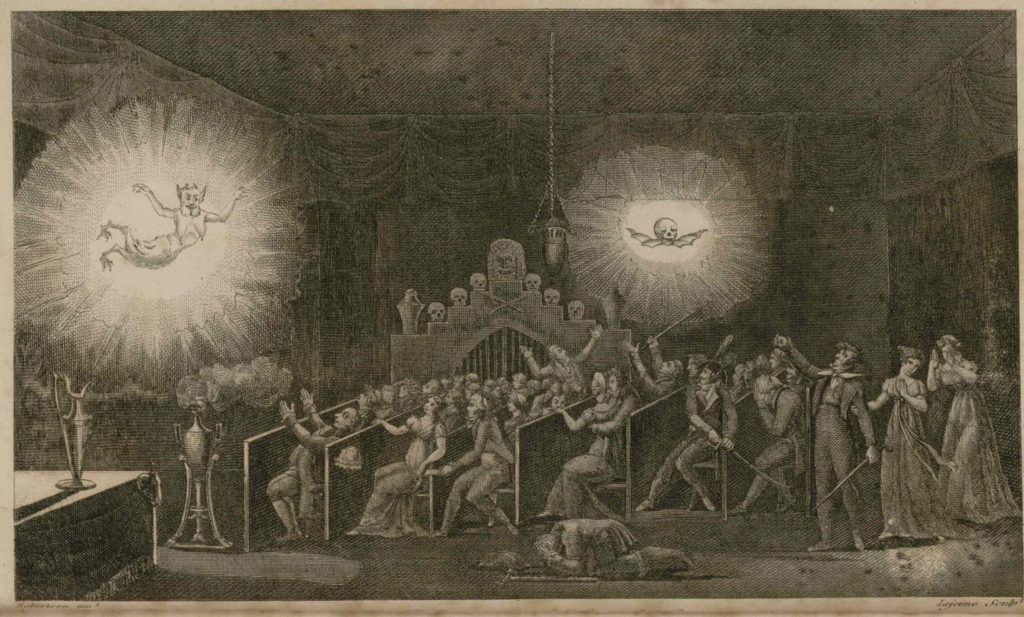

All of this intensified the experience of his audience. Robertson could begin with a slightly open diaphragm and the Fantoscope positioned close to the screen creating a small, faint image of a spirit seemingly a great distance away. Wheeling the Fantoscope away from the screen and opening the diaphragm made the spirit image rapidly larger and brighter thus terrifying the audience with its approach. By using multiple slides painted by his own artistic talent, he created an additional illusion that animated the spirit’s face.

But then Robertson added a layer of showmanship that generated another stratum of intensity. He usually eliminated all sources of light during his shows to place the audience in total darkness for several minutes at a time. He would also lock the theater doors so that no audience member could exit the show once it had started.

But he wasn’t done yet. He passed his glass slides through wisps of smoke thereby blurring the image and he added sound effects such as thunder clapping, bells ringing, and ghost calls. Robertson wrote, “I am only satisfied if my spectators, shivering and shuddering, raise their hands or cover their eyes out of fear of ghosts and devils dashing towards them.”

However, Robertson was also a scientist. Though he played his shows straight, like any good illusionist, he closely guarded the secrets of his phantasmagorie he made clear in his closing remarks that what the audience had seen was not sorcery but science. In his book The Wonders of Optics, Fulgence Marion wrote,

Robertson generally ended his entertainment with an address something like the following:

“We have now seen together the wonderful mysteries of the phantasmagoria. I have unveiled to you the secrets of the priests of Memphis. I have shown you every mystery of optical science; you have witnessed scenes that in the ages of credulity would have been considered supernatural. You have, perhaps, many of you, laughed at what I have shown you, and the gentler portion of my audience have possibly been terrified at many of my phantoms; but I can assure you, whoever you may be, powerful or weak, strong or feeble, believers or atheists, that there is but one truly terrible spectacle – the fate which is reserved for us all ;” and at that instant a grisly skeleton was seen standing in the middle of the hall.

[Text and image above are from skullsinthestars].

Robertson eventually had to reveal his methods when he filed a lawsuit against two of his assistants who had struck out on their own. This, of course, led to numerous imitators and the only element that kept Robertson a step ahead of his competitors was his use of a ventriloquist named Fitzjames who added a unique element to his shows.

Even one of my favorite writers, Charles Dickens, knew of Robertson’s reputation. As reported in the post about Robertson on skullsinthestars, Dickens wrote about Robertson in his weekly magazine Household Words and described him thusly:.

He was a charmer who charmed wisely, – who was a born conjurer, inasmuch as he was gifted with a predominant taste for experiments in natural science, – and he was useful man enough in an age of superstition to get up fashionable entertainments at which spectres were to appear and horrify the public, without trading on the public ignorance by any false pretence.

So, when you visit Père-Lachaise, reach Robertson’s tomb and see this,

it should now make sense. The reason for the image on the other side of his burial chamber

with the crowd staring at the rising balloon, however, might not be as clear.

To grasp the importance of this symbolism, you need to recall that on his first stay in Paris, Robert studied under Jacques Charles and that Charles launched the world’s first hydrogen balloon. Charles went on to become something of a mentor to Robert and Robert went on to become enamored of balloon flight.

Unlike his work with optics, the scientific work Robert performed in his balloon ascents was generally uncharacteristically sloppy and unoriginal – perhaps he was too captivated enjoying the freedom of flight to properly focus on his scientific work. What Robert did accomplish was setting an altitude record in a Montgolfière-style hot air balloon (or globe aérostatique) when he soared to 7,300 meters on 18 July 1803. (As a point of reference, this height would have left him some 1,500 meters shy of reaching the peak of Mount Everest but would have cleared Mount Blanc by 2,500 meters.)

(Invented by the brothers Joseph-Michel Montgolfier and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier the Montgolfière established the principles and methods by which hot air balloons still fly today. The brothers had their first recorded flight in Annonay, France on 4 June 1783 sending their balloon two kilometers distant and reaching an altitude above 1,600 meters in a flight that lasted 10 minutes. On 21 November of that year they launched the first free hot air balloon with human passengers. The flight lasted 25 minutes and is generally credited as the first untethered manned flight of any kind. Ten days later on 1 December, Jacques Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert {no relation to Robertson} piloted the first gas balloon and flew for more than two hours.)

In 1806, Robert returned to the sky when he piloted another hot air balloon nearly 30 kilometers from Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen to the town of Roskilde on the Danish island of Zealand. It was one of the longest flights of its time. And now the balloon and balloon watchers make sense, too.

Missing from the gravesite (at least as far as my casual observations took me) were references to his fascination with experiments in electricity. It was Robertson who introduced the work of Alessandro Volta (inventor of the battery) to French scientists of the time. Robertson was 74 years old when he died in Paris on 2 July 1837.

In the final two stories, we’ll meet a ghostly ghost writer and a man who has a well-rooted place in both French history and in Paris’ largest necropolis. So stay tuned.