Today is the penultimate installment of my Père-Lachaise Chronicle and will examine the life and contributions of Auguste Maquet. Once again, David led us to this gravesite.

Did Dumas do less?

The trial and triumph of Auguste Maquet.

Is Auguste Maquet the greatest French writer you’ve never heard of? This brief report won’t answer that question but it might provide some material to ponder.

Auguste Maquet was the eldest of eight children and was born in Paris on 13 September 1813. In my research I discovered that Patricia and I have a curious connection to him.

Maquet was another of the exceptionally smart people we’ve encountered in the tour of Père-Lachaise. In his case, he was bright enough to complete his studies in history at the Lycée Charlemagne and transition into a teaching position there (well, a substitute teaching position) at age eighteen. The poets Théophile Gautier and Gérard de Nerval attended the school at the same time and Maquet developed a friendship with the two older boys. (The former is buried in the cemetery at Montmartre. The latter in Père-Lachaise.)

So, how are Patricia and I connected to him? The hint is in the name of his school. Perhaps you remember this photo

from the post A real Downie day – the highlights edition about which I’d written,

We had a sense of the value David would add to our day within seconds of our introductions.

In front of us was a jagged stone wall that Pat and I had walked past without noticing on our way to dinner last night. It jutted onto the sidewalk like an inverted leg of a pair of tapered pants – wide at the bottom and narrow at the top – daring a student from one of the nearby schools to scale its lower section that was perhaps a bit more than two meters high and tag it with some graffiti.

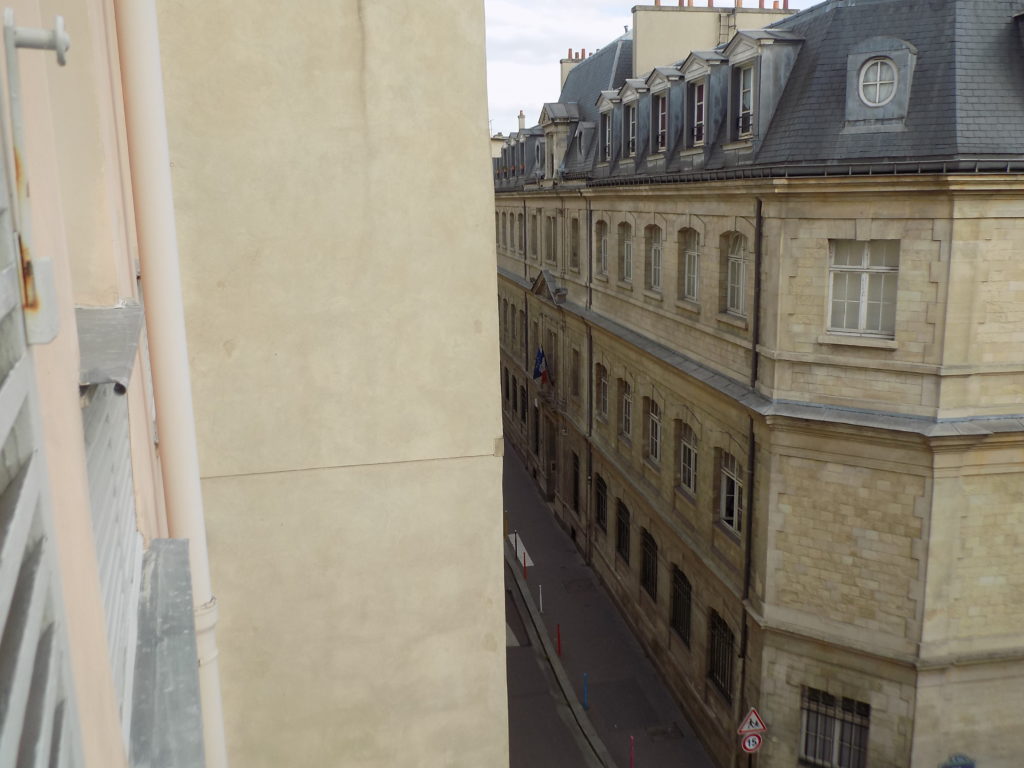

Or if you were curious enough to poke around the photos folder from the day of our return to Paris, you saw this view from our flat.

In both instances, the building on the right is the Lycée Charlemagne. Maquet, Pat, and I were neighbors across time.

When his teaching career stalled, Maquet decided to embark on a career as a writer. In 1835, at the ripe old age of 22, he announced, “I am going to ask from literature what the University refuses me: glory and profit.”

The declaration was probably not quite as brash and unfounded as it might superficially seem. Indications are that Maquet had an ongoing relationship with both Gautier and de Nerval and it wouldn’t strain credulity to infer that he was influenced and aided by his older friends.

Gautier and de Nerval were members of an avant-garde writer’s group called Les Bousingos who wrote in a style known as freneticism or frenzied romanticism. Freneticism expressed a desire to attain some absolute state while confronting the impossibility of achieving it. Some of Maquet’s poems and short stories were published under the pseudonym Agustus Mac-Keat and by 1836 he was on the staff of Paris’ daily newspaper Le Figaro. But the ambitious young man remained far from achieving “glory and profit.”

Much of what kept him from his goal resulted effectively from the catch-22 of the publishing industry and popular literature in the middle third of the 19th century. Whether one looks at England and Charles Dickens or at France and the writings of Alexandre Dumas, there can be little doubt that the serialized novel was, perhaps, the dominant literary form of the day. Publishers, however, were unwilling to take risks on unknown writers. So it should come as no surprise that when Maquet shown below [From Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

submitted his novel Le Bonhomme Buvat to La Presse (the first penny press newspaper in France), he received this response, “You are not a name, and we only want names.” (Fortunately, I can publish my own serial – well-written or not – without the intervention of a publisher. On the other hand, I’m seeking neither glory nor profit.)

Thus, when Maquet’s friend de Nerval introduced him to Alexandre Dumas it was likely as premeditated as it was spontaneous. Maquet reportedly gave a copy of his play Le Soir de Carnaval (which had also been rejected by publishers) to Dumas, who might or might not have rewritten parts of it. He certainly changed the title and the play was published under its new name Bathilde. Dumas credited Maquet as a co-author. While this marked the beginning of a long collaboration between the two it was not, as Rick said to Louie, “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Grateful for Dumas’ assistance, Maquet presented the great man with a copy of Le Bonhomme Buvat sometime around 1840. Dumas again provided a new title, Le Chevalier d’Harmental and submitted it for publication. Some accounts assert that Dumas submitted it with both names but the publisher removed Maquet’s. Others state that Dumas simply claimed the book as his own. Whichever was true, the book was published without Maquet’s name although he did receive the rather remarkable sum of 8,000 francs at the time of its publication. Profit, at least, was now within the younger writer’s grasp.

It was apparently an open secret that Dumas, who was known to be profligate in dispensing both his sexual favors (He allegedly had 40 mistresses in his lifetime and had by this point already fathered a son and a daughter. Dumas married Ida Ferrier in 1840 but she was not the mother of any of his four children.) and his money, used a workshop of writers who came to be called nègres (literally Negroes but also ‘ghost writers’) – a term popularized in a biographical pamphlet by Eugene de Mircourt. (Mircourt’s choice was probably imbued with a double meaning referring not only to the hidden nature of these unnamed assistants toiling in dark obscurity but also to Dumas’ lineage. His paternal grandfather was black.)

[Dumas in 1855 by Nadar – Google Art Project.]

Maquet was, without question, the most prominent of these nègres and over the decade of the 1840s the pair collaborated on many of Dumas’ most famous and greatest works including The Three Musketeers, The Man in the Iron Mask, and The Count of Monte-Cristo.

By the mid-1850s Maquet’s frustration with the lack of “glory and profit” he thought he deserved intensified. So, in 1858, he sued Dumas attempting to gain joint rights to their body of work. During the trial, Dumas admitted that Maquet had assisted him but unwaveringly insisted that the true creative spark was his. In the verdict, Maquet received a significant award of financial damages thus gaining the “profit” but he was denied the “glory” when Dumas retained sole ownership of their output.

How critical was Maquet’s role in the production of Dumas’ greatest works? To those loyal to Dumas and his memory such as Safy Nabou, who directed the 2010 film L’Autre Dumas, Maquet was little more than an assistant. In an interview he said, “Maquet did not have the genius of Dumas; he could spend hours and hours writing but it didn’t change anything. You can’t learn genius.” For Nabou, Maquet was a plow horse and nothing more.

Conversely, the novelist Bernard Fillaire wrote an essay supporting Maquet. “There is a tendency to dismiss him as a drudge and that’s just wrong. Of course he wasn’t a Balzac or a Dickens … but he definitely had talent.” For Fillaire, Maquet was more akin to the farmer sowing the seeds that stimulated Dumas’ creativity.

That Maquet had discipline where Dumas did not is not in question. That Maquet and Dumas collaborated is also a point of no dispute. The only question is the degree of creativity each provided. The likely truth is that the pair were more symbiotic than either would have admitted. After their very public and very bitter literary divorce, both men continued writing and the notoriety allowed Maquet to publish a series of moderately successful though mostly forgotten novels. Dumas also extended his oeuvre but never replicated the success he’d achieved while collaborating with Maquet.

Fillaire probably summed it up well when he wrote, “There was this extraordinary alchemy between them. They needed each other. When Maquet left Dumas, neither did anything else that was really excellent. Dumas did nothing more of any note. Maquet went on to write a lot.”

The nègre might have had his revenge at the end of their respective lives. Maquet outlived Dumas by 18 years and died a wealthy man while Dumas died in poverty. One literary legend has it that in the library of his château at Sainte-Mesme, Maquet had a copy of Les Trois Mousquetaires rebound and re-attributed: “par A Dumas et A Maquet.”

Dumas was originally buried in Villers-Cotterêts – the town of his birth – but his body was exhumed and now lies in the Panthéon in Paris. Maquet has his tomb in Père-Lachaise. And it’s here that he made his final claim for his authorship.

(It’s more easily seen by enlarging the picture.)