HEADNOTE: All artworks in this post appear courtesy of Artlandish Aboriginal Art Gallery. Special thanks to Kristie Linklater for granting permission.

HEADNOTE 2: This overview is a superficial summary presented within the framework of my limited understanding.

Now that we’ve established that the first people reached Australia at least 60,000 years ago probably from Maritime Southeast Asia we can begin to look at the belief system that ties them to Country with greater intensity than any other culture I’ve encountered. I’ll do this mainly through the understanding I gained through my RS trip and subsequent research. First, I need to provide a definition of

Country.

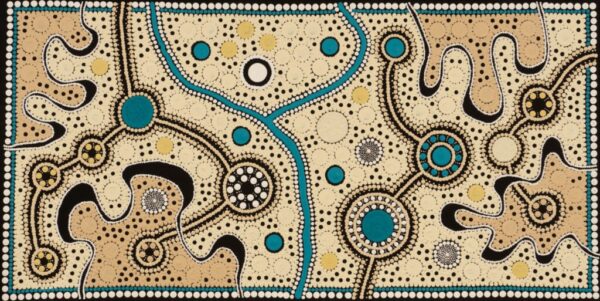

[Country by Delvine Petyarre]

Country is the term often used by Aboriginal peoples to describe the lands, waterways and seas to which they are connected. The term contains complex ideas about law, place, custom, language, spiritual belief, cultural practice, material sustenance, family and identity.

Critical to this connectivity is the notion of The Dreaming (sometimes called Dreamtime). When considering land in particular, Australian Aboriginal people generally view themselves as caretakers or custodians of their lands rather than owners in the western sense. This is because The Dreaming isn’t a single creation event (or even a series of creation events) but is rather an ongoing act of creation. While The Dreaming explains the origins of Country and the workings of nature and humanity, it also regulates the understanding of family life, relations between the sexes, and people’s obligations through law and culture. Ceremony passes Dreaming stories and their lessons across generations.

Aunty Munya, an Indigenous leader in the land rights movement, explains, “Rather than ‘owning’ the land, we believe that we belong to the land, in which there is no concept of individual ownership but rather one of joint belonging, collaboration and care of the land. My own personal view is that these are everyone’s Ancestors, not just of Aboriginal people. They are the ‘Ones Who Came Before Us’ and their spirits remain in the land, which is why Country is so sacred.”

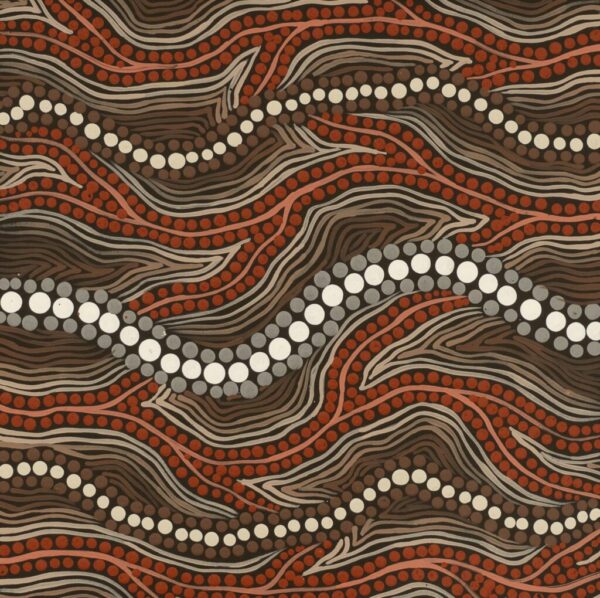

[Journey Tracks to Sacred Water Sites by Tony Sorby]

Processing Creation

Aunty Munya’s last statement expresses one of the critical differences between Australia’s First People and other cultures. The Abrahamic creation story is one of an all-powerful deity creating the world from nothing. Some Native American creation stories involve deities in the form of divine beings. Others involve animals. While the creation stories of Australia’s First People often involve supernatural beings, they also include ancestral spirits. Crucially, these ancestors “remain in the land.” Thus, when an Australian Aboriginal person is displaced from their native land, it’s not merely severing the connection with their living family (an act with its own complications), it’s also dissociating them from all of their ancestors and the ongoing process of creation.

This is another element of Australian Indigenous belief that differentiates it from others – at least others I’ve encountered. All Abrahamic creation events happened at an undefined moment in the past. Similarly, for Native Americans, creation is typically depicted as a completed past event. Not so for the First People of Australia. Their ancestors are still present. The Dreaming is a continuum of all time – past, present, and future. Creation is an ongoing process in which the actions of these ancestors are ever present always shaping and reshaping Country. For an Indigenous Australian, the notion of treating Country in any way other than as sacred is outside their comprehension.

(Because Australian Aboriginal People have a cyclical cosmology, destructive elements are present within their notion of ongoing creation. To me, their view seems qualitatively different from the endless cycle of universal formation, existence, destruction, and emptiness present in Buddhist cosmologies in part because they are active participants in shaping the process.)

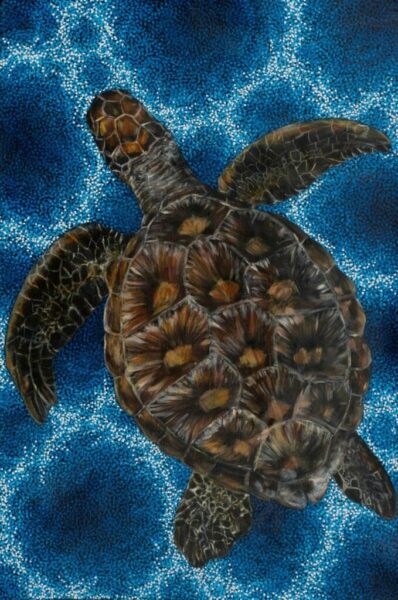

[Spirits in the Wind by Davinder Hart]

So what time is it?

By this point you should be unsurprised to learn that the concept of time, like their concept of Country, exists very differently in the culture of Australia’s First People from the way time is perceived in the west. I don’t mean to imply that all First People share identical temporal perceptions. However, their languages generally don’t have a single word that equates to time. Instead, they have rich and varied vocabularies describing temporal concepts correlating with natural cycles such as seasons or with specific events.

There were as many as 600 language groups in Australia prior to the arrival of Europeans so diversity in perceiving time is inescapable – as it would be with any subject. A language such as Jiwarli (spoken in the Pilbara region of Western Australia) uses verbal inflections to differentiate past, present, future. However, there are some other concepts with greater universality across the cultures of First People. As Dr Michael Donaldson wrote in his 1996 paper The End of Time? Aboriginal Temporality and the British Invasion of Australia,.

History, present and intimate, was not about events and persons strung like beads through time, but about the past containing the present, and the present representing the past in accordance with the Dreamtime law. Time was enveloping. Both cyclical and circular, it accorded with the need for seasonal movement, the aggregation and disaggregation of groups.

The People

were profoundly committed to ensuring that this annual cycle was accomplished properly and with appropriate ceremony. Being at the right time and in the right place was crucial, for if this did not happen, then they thought the earth would `harden’, and might not be as fruitful as it could be. Famine, deluge, drought, disease and scarcity were understood to occur because of the failure on the part of humans and the earth itself to honour their respective bonds with each other through the Dreaming, each requiring the active participation of the other.

And,

Daily time was marked by daybreak, sunrise, morning, midday, afternoon, late afternoon, sunset, evening and night. Time could be and was counted by sleeps, moons, phases of the moon and by seasons. Seasons were marked by religious ceremony, by temperature, winds and weather; by the appearance and disappearance of particular people and groups of people; the arrival of certain blossoms, plants, insects, birds, fish, animals, each according to their locality.

Still further,

The causal one-to-one relationship, the unidirectional linear causality basic to European thought since the classical Greeks, although not ignored, was not privileged. What was more important was that the natural cycles continued to be circular, one sign called forth by and calling forth the next, part of the movement from place to place, phase to phase, until the circle was completed and the same event occurred again in the place that contained it. All that happened was already present, with movement at the appropriate time, the calling out of the landscape, the naming of the names, confirming what simultaneously was, is, and would be. Life was lived, in Stanner’s memorable expression, in the ‘everywhen’.

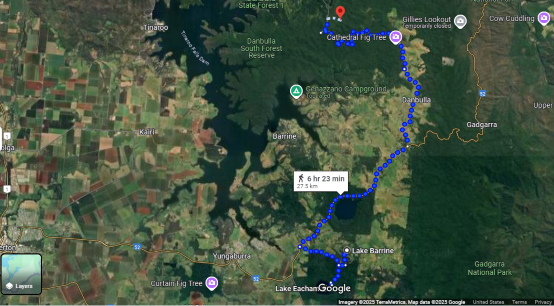

[Palaarn by Tarisse King & Tegan Hamilton]

The geological connection

Because Australia’s Indigenous People perceive creation as an ongoing process, The Dreaming, unlike fixed creation stories can incorporate actual events. As a result, Aboriginal People relate stories that geologists can confirm. Here are some examples:. The screen capture from Google Maps shows three crater lakes (Lakes Eacham, Barrine, Euramoo) on the Atherton Tableland in far northern Queensland.

Aboriginal Dreaming stories described the volcanic origin of the three lakes. Geologists have confirmed volcanic activity and date it to approximately 10,000 years ago. Similarly, the most recent volcanic eruption on the Australian mainland occurred in the Limestone Coast region of South Australia – specifically Mount Gambier and Mount Schank. Dreaming stories from the Bungandidj People relate and confirm these eruptions.

Both the Palawa and the Kurnai People have Dreamings about the formation of the Bass Strait that separates Mainland Australia and Tasmania.

The Kurnai Dreaming tells this tale (taken from Australian Geographic).

Long ago there was land to the south {of Gippsland} where there is now sea, and that at that time some children of the Kurnai, who inhabited the land, in playing about found a turndun [bull-roarer or musical instrument], which they took home to the camp and showed to the women [which was forbidden]. Immediately, it is said, the earth crumbled away, and it was all water, and the Kurnai were drowned.

In this story we can see how The Dreaming regulates people’s obligation through law and culture. Geologically, Tasmania and Australia separated about 12,000 years ago as sea levels rose due to glacial melting. Other Dreamings correlate similarly with other events.

While it can certainly be said that both American and Australian First People share a general belief in a spiritual connection between humans, animals, plants, and the land, the Native American tradition believes in the existence of spirits or supernatural entities that inhabit the natural world while the Indigenous Australian tradition emphasizes ancestral connection through the ongoing process of creation called The Dreaming.

As AIATSIS notes, the Aboriginal concept of Country “contains complex ideas about law, place, custom, language, spiritual belief, cultural practice, material sustenance, family and identity.” These are distinct, original, and complex concepts stemming from the world’s oldest culture.

A wonderfully thought out interesting piece Todd. My favourite part was your quote from Aunty Munya, “Rather than ‘owning’ the land, we believe that we belong to the land”. 🙂

Thanks, Kristie. Getting it right (or at least close to right) was important to me. I hope you found my use of your gallery’s art as appropriately additive in supplementing the narration.

Again, thoughtful and comprehensive. Some excellent research. Relating the Dreaming stories with natural events is a concept I have only touched on – you have given it more depth. Thanks Todd.

The artworks are special.

Testing a thoughtful comment.