House and (a more traditional) Garden II.

As I noted previously, the earliest flower that sprung from Monet’s passion for gardening came when he created the Clos Normand – a space Monet referred to as his life’s greatest work. In designing this garden, he transferred the knowledge of color, light, and perspective he’d developed from his paintings to it. Monet was so passionate about gardening and horticulture – about which he was exceptionally well read – that he continued supervising the care of the Clos Normand even after he had hired seven gardeners to tend it.

The garden is so deceptively linear and orderly that the straight paths are apparent even on the satellite photo. Although it wasnвҖҷt in full profusion during our visit, this picture from Wikimedia shows how order and disorder meet along the garden’s central path.

These pebble-lined paths are quite easy to follow but, if you begin to look closely you see that all is not as orderly as they might lead you to think. Roses, peonies, azaleas, day lilies, and many other flowers spring up in confused profusion from any angle and sight line you choose. The colors, varying shades of red and yellow, orange and purple, or white and pink collide in a simultaneously harmonic and dissonant fanfare of attention seeking vibrancy.

As his fame grew, artists began congregating in Giverny. Drawn not only by Monet but the landscapes – both natural and those Monet had created – and the congenial atmosphere, many American Impressionists began visiting Giverny in the summers. By 1887, painters such as Willard Metcalf, Louis Ritman, Theodore Wendel, and John Leslie Breck were not merely taking extended summer vacations but had settled in the town. Another American painter, Theodore Earl Butler developed an even closer relationship with the master when he married Monet’s stepdaughter Suzanne HoschedГ© in 1892.

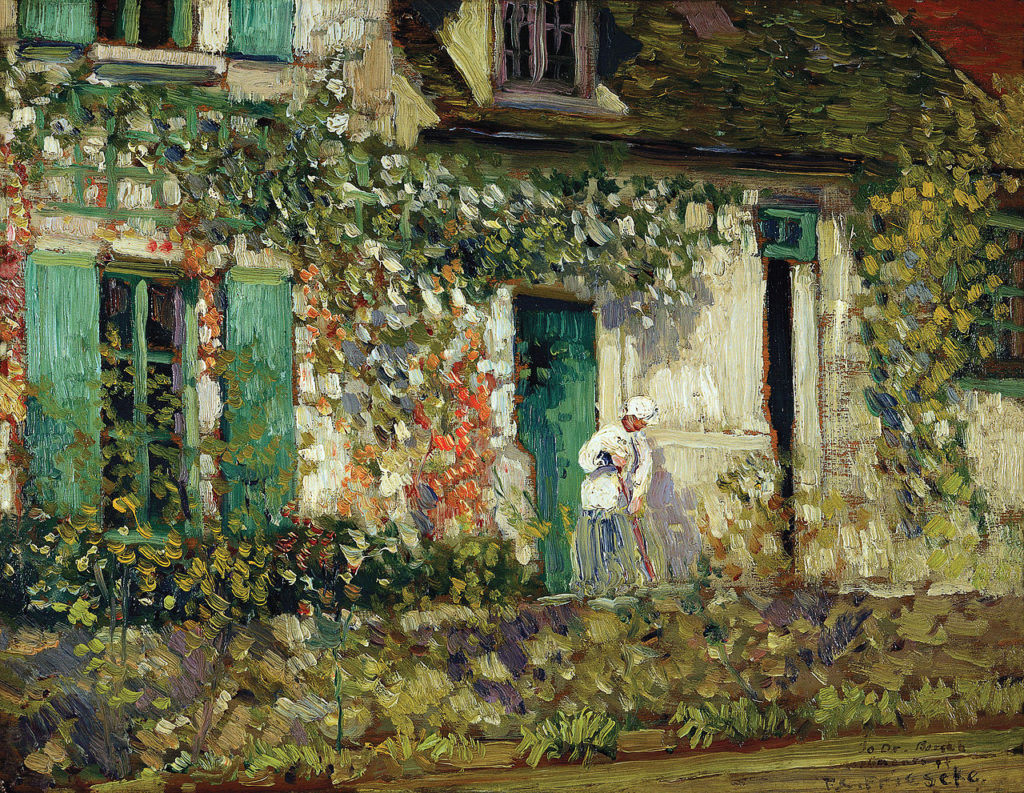

In 1906, yet another American, Frederick Frieseke moved into the house adjacent to Monet’s. Frieseke became well known for painting women in outdoor settings. Characterized by a pastel palette, his carefully constructed paintings typically juxtaposed offsetting patterns. Here is Frieseke’s painting of his house in Giverny

(from Wikimedia.)

and this is Monet’s house in 2018.

Frieseke was soon joined by other Americans looking to incorporate elements of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism into their own more or less cohesive vision. These included Richard Edward Miller, Guy Rose, Lawton Parker, Edmund Greacen, and Karl Anderson. In December 1910, these six shared a show at the Madison Gallery in New York where they were dubbed “The Giverny Group.” Shortly thereafter, the art writer Christian Brinton coined the term Decorative Impressionism to describe the group’s style.

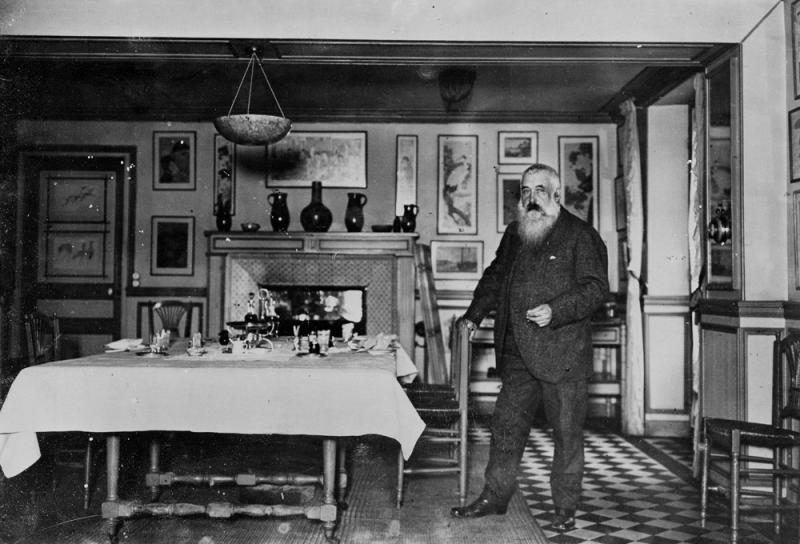

Stepping inside, we find a house that has been preserved and restored to look much as it did when Monet lived there. From the artist’s studio filled with reproductions,

to the blue kitchen,

to the yellow dining room,

it’s all there as it was. And if you need proof of its authenticity, compare the picture above to this one that I happened upon on the Positive Eating Positive Living blog.

When we were done walking about the estate – including stopping in the gift shop which was originally the large studio Monet had constructed specifically to paint the large works we’ll see when we return to Paris, Patricia and I walked along the Rue Claude Monet to the church and graveyard where the Monet family is buried. You can see photos from that walk and our time in Vernon and in the gardens here.

A world premier at the Impressionism Museum in Giverny.

If you took a few minutes to look at the photo album I linked above, you saw a small selection of photos of some of the paintings in Giverny’s museum that I was able to take in the short time before we convened as a group in the lower level auditorium to hear the first – or as it turned out – the first two performances – of Wang Jie’s composition constructed around the musical lots she drew at the American Church in Paris a week ago nearly to the hour.

On the night of our magnificent cheese sampling four nights earlier, Jie had given us a glimpse of the piece and a peek into her creative process.В At that time, she made it clear to Fred that she wanted no suggestions about the direction of the composition or even its title. By the next morning, I, of course, had convinced myself that I should step over that boundary and suggest a title – both cheeky and tongue in cheeky. Since we first heard parts of Jie’s work after our cheese tasting event, I suggested the title AprГ©s le Fromage. Wisely, she ignored me.

When we first boarded the Amadeus Diamond in Paris, the ship was docked near the Mirabeau Bridge or in French, Le Pont Mirabeau. We sailed beneath it both on our departure and would do so on our return. As it happens, Guillaume Apollinaire titled one of his poems Le Pont Mirabeau. (I hope you recall that it was Apollinaire who wrote the calligram in the shape of the Eiffel tower.)

Written in 1912 just six years before his death at the age of 38, many believe the inspiration was the end of his relationship with the female painter Marie Laurencin. Considered ultra-modern in form, he constructed the poem with short verses, a refrain that repeats throughout the poem like a song, and without punctuation. The melancholy poem uses the image of the bridge spanning the flowing Seine to explore love and the passage of time.

Fred’s recital of the poem is difficult to hear on this video of the performance so I’ve reproduced the poem in both the original French and an English translation (though not likely the translation Fred read).

Le Pont MirabeauВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The Mirabeau Bridge

Sous le pont Mirabeau coule la SeineВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Under the Mirabeau bridge flows the

В В Seine

Et nos amoursВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В And our loves

Faut-il quвҖҷil mвҖҷen souvienneВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Must I remember them

La joie venait toujours aprГЁs la peineВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Joy always followed pain

Vienne la nuit sonne lвҖҷheureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The night falls and the hours ring

Les jours sвҖҷen vont je demeureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The days go away I remain

Les mains dans les mains restons face Г faceВ В В В В В В В Hand in hand let us stay face to face

Tandis que sousВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В While underneath the bridge

Le pont de nos bras passeВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Of our arms passes

Des Г©ternels regards lвҖҷonde si lasseВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The water tired of the eternal looks

Vienne la nuit sonne lвҖҷheureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The night falls and the hours ring

Les jours sвҖҷen vont je demeureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The days go away I remain

LвҖҷamour sвҖҷen va comme cette eau couranteВ В В В В В В В В Love goes away like this flowing water

LвҖҷamour sвҖҷen vaВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Love goes away

Comme la vie est lenteВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Life is so slow

Et comme lвҖҷEspГ©rance est violenteВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В And hope is so violent

Vienne la nuit sonne lвҖҷheureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The night falls and the hours ring

Les jours sвҖҷen vont je demeureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The days go away I remain

Passent les jours et passent les semainesВ В В В В В В В В В В Days pass by and weeks pass by

Ni temps passé                                    Neither past time

Ni les amours reviennentВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Nor past loves will return

Sous le pont Mirabeau coule la SeineВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Under the Mirabeau bridge flows the Seine

Vienne la nuit sonne lвҖҷheureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The night falls and the hours ring

Les jours sвҖҷen vont je demeureВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В The days go away I remain

The days may be going away but Patricia and I will remain in Paris for five days after our ship docks there tomorrow morning.