The Other End of the Telescope

In the course of this series I’ve written about many Olympic champions – Birgit Fischer being the most recent. Some might consider it a stretch to deem Eric Moussambani Malonga (sometimes called Eric the Eel)

[Photo from Swimming World.]

a champion since, as a swimmer from Equatorial Guinea, he finished with the slowest time in Olympic history in his event. He needed 1:52.72 seconds to finish the 100 meters freestyle. The gold medal winning time that year by Pieter van den Hoogenband from the Netherlands was 48.30 seconds. So how, you might wonder did Eric the Eel even make it into the Olympic pool? Here’s the answer:

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has a wildcard system they call “universality rules” that admit athletes from developing countries who haven’t met the qualifying standard but are intended, as one Daily Show correspondent once described them, “to encourage participation in White people sports.”

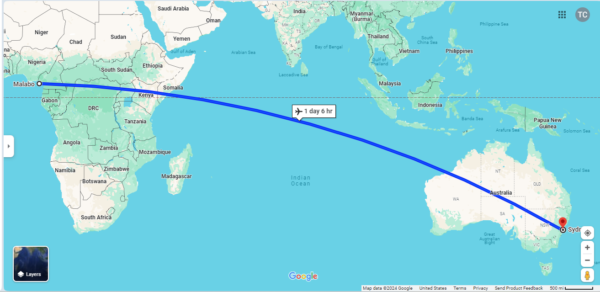

One day, Moussambani, who had played basketball and soccer heard a radio announcement that his country’s Olympic Committee was seeking swimmers to participate in the Sydney Olympics. When no other athletes appeared at the hotel in Malabo, the capital of Equatorial Guinea, Moussambani proved that he could swim by covering the length of the hotel’s 12-meter pool and was rewarded with eight months to train himself in a country with no Olympic-size pools and then a ticket to Sydney some 15,ooo kilometers away.

[From Google maps.]

Moussambani described his experience to CNN,

When I arrived I just went to the swimming pool to see how it is. I was very surprised, I did not imagine that it would be so big.

My training schedule there was with the American swimmers. I was going to the pool and watching them, how they trained and how they dived because I didn’t have any idea. I copied them. I had to know how to dive, how to move my legs, how to move my hands.

I learned everything in Sydney. I didn’t know how to dive, anything. While they were training I was watching them. I was alone. I didn’t have a coach.

As Moussambani took his position on the block for his heat, only two competitors stood beside him . Both were disqualified for two false starts and Moussambani faced the pool alone. Perhaps riding a wave of adrenaline, Moussambani described his race as swimming against the pool and in the same CNN story said,

The first 50 meters I did very well. I did it with a lot of energy. When I was coming back to complete the 100 meters I was exhausted. If you watch the video, I couldn’t feel my legs. I was feeling like I wasn’t going to go any further. I was moving in just one place.

The crowd was singing, ‘Go go go go!’ So I did my best to complete it. But once I completed it I was exhausted. I thought, ‘Phew, my god!’ All my muscles were tired. So when I went in to the changing room I just collapsed on the floor and lay there. I couldn’t even breathe.

He later told the Sydney Morning Herald,

I went back to my apartment in the Olympic village and I slept from 11am to 4pm. When I woke up, on the television I could see my pictures. I thought I did something wrong.

“When I went to the Olympic restaurant where the athletes eat, that’s when people started asking me for autographs and pictures. That’s when I realised I became very famous.

That was a big experience for me because I used to be a very shy guy. People started to look for me in the village.

Subsequent to those Olympic Games, his goggles sold in a charity auction for 4,638 Australian dollars and his swim trunks are on display in the NSW Hall of Champions according to one news report. Eric the Eel not only continued to swim, he lowered his personal best time by more than a minute and became Equatorial Guinea’s national swimming coach. He dreams that one day a swimmer from his country will win an Olympic medal although he concedes that it’s unlikely to happen.

What is likely is that more people remember Eric the Eel Moussambani’s 100 meter swim than those who recall that of Pieter van den Hoogenband.

A hometown heroine of sorts

It would be a sin of omission to write about the 2000 Olympics and not include some discussion of Cathy Freeman. Cathy Freeman was born in Slade Point, Macay, Queensland in 1973 and she would become the first aboriginal Australian to win an Olympic medal – silver in 1996. Her father Norman was a full-blooded member of the Birri Gubba People. Her mother, as she would learn in 2008, had a blended heritage of Australian Aboriginal, Chinese, and English.

Although she spent her earliest life in public housing, she had a somewhat nomadic youth due in part to the itinerant nature of her stepfather’s work.

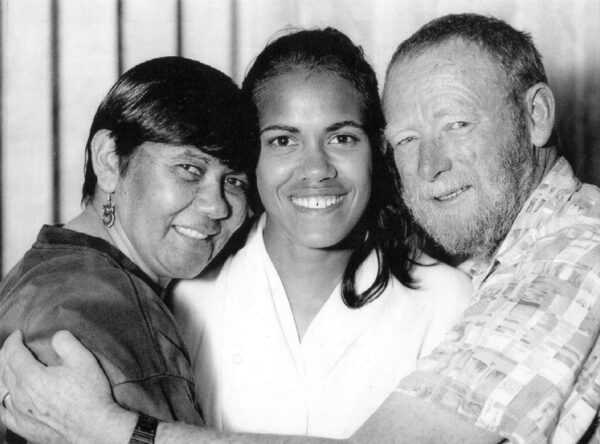

[Image of Freeman with her mother and stepfather from National Museum of Australia by Anthony Weate Copyright News Ltd.]

She wrote in her autobiography Born to Run that she was hooked on running from her first race at age eight and she had considerable early success. With her stepfather Bruce Barber serving as her first coach, by age 14, she held national titles in high jump, as well as the 100, 200, and 400 meter sprints. It was then that she told her high school counselor that her only ambition was to be an Olympic athlete.

At age 16, she was part of Australia’s gold medal winning 4×100 meter relay team at the 1990 Commonwealth Games making her the first Aboriginal person to win a gold medal in that competition. She made her first Olympic Games appearance in Barcelona in 1992 but failed to reach the final in the 400 meters – the race that had become her specialty.

She returned to the Olympics in Atlanta in 1996 where she finished second to France’s Marie-José Pérec. She captured gold at the world championships in 1997 and 1999. And, in 2000, the Olympics were coming to Sydney.

While she chafed at being considered a role model, Freeman had grown more outspoken about the challenges of Australia’s Aboriginal People. After her gold medal victories in the 1994 Commonwealth Games, she carried an Aboriginal flag as part of her victory lap.

She was quite outspoken about Prime Minister John Howard’s refusal to offer a formal apology to members of the ‘Stolen Generations’. (This term describes the thousands of children who were forcibly removed by governments, churches and welfare bodies to be raised in institutions, fostered out or adopted by non-Indigenous families, nationally and internationally. Visit the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Islander Studies for more information about the Lost Generations.)

When the Sydney Organizing Committee chose her to light the Olympic flame at the Opening Ceremony, because Australian Olympic Committee President John Coates believed that having an Aboriginal athlete light the flame would send a powerful message to the world about reconciliation and Indigenous representation she became a target of resentment from both sides. There were those who supported the Howard government’s positions regarding Aboriginal People and thought she was undeserving of the honor while, on the other side, there were Aboriginal People who had urged Freeman to boycott the Games.

Freeman not only lit the flame,

[Image from 9News Australia.]

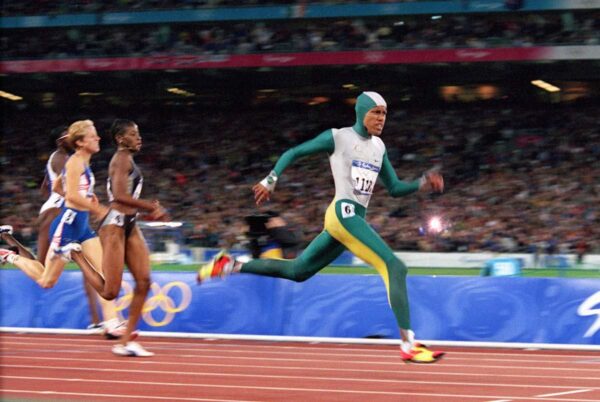

she won the gold medal,

[Image from Australia Digital Classroom.]

and she once again carried both an aboriginal and Australian flag in her victory lap.

[Image from The Guardian.]