We set off early Thursday morning with a salute from the hotel alpaca and friend.

Although we only needed to walk a few hundred meters from the Tunupa Lodge to the train station, we needed to arrive well before our scheduled departure time of 08:30 to allow sufficient time for our documents to be inspected. The hour and a half ride largely follows the (at that time) roiling Wilqamayu (Urubamba) River

from Ollantaytambo to the town of Aguas Calientes which sits at the base of the citadel of Machu Picchu. We were on a bit of a tight schedule so Berner made it clear that, when we arrived in Aguas Calientes, if we thought we were walking through a market it was a hallucination. He told us that while Aguas Calientes does indeed have an open-air market, it only exists for people walking to the train station and not from it.

Our schedule allowed just enough time to walk to the hotel, check-in, leave our bags, and use the toilet. This last stop is crucial since the toilets at the site Hiram Bingham named Machu Picchu are just outside the entrance and once you enter you can’t leave to use them because the guards won’t let you re-enter. While Jan and Jill were making use of the hotel facilities, I made certain I was toting spare batteries for my camera. I was the last in our group to make the preparatory precautionary stop.

It is no surprise now.

We had a short walk along the Aguas Calientes River (a Wilqamayu tributary) to the bus that would take us up the mountain to what is, I suspect, the place that will be the highlight for most first-time visitors to Perú. It’s almost certainly the most highly anticipated.

The attentive among you will have noticed that I wrote above that Hiram Bingham named the place we are about to visit. You should certainly know by now that we don’t know the name the Inkas used for this place or even if they named it at all. Curiously, despite this plaque honoring him,

most historians now agree that Bingham was not the first western explorer to “discover” it. There is considerable controversy surrounding not only the discovery of Machu Picchu but also over who can legitimately claim ownership of not only the artifacts but the land itself. According to a 2009 article in Smithsonian Magazine,

“The presence of several German, British and American explorers is recognized, and that they had drawn up maps,” says Jorge Flores Ochoa, a Peruvian anthropologist. Bingham “had more academic knowledge…. But he was not describing a place that was unknown.”

and a 2008 story in the New York Times reported,

Soon after Mr. Bingham led his expeditions to Machu Picchu, claims surfaced that a British missionary, Thomas Payne, and a German engineer, J. M. von Hassel, had beaten him there. And maps found by historians show references to Machu Picchu as early as 1874.

and,

Records show that the German, Augusto R. Berns, purchased land in the 1860s opposite the Machu Picchu mountain, built a sawmill on his property and then tried to raise money from investors to plunder nearby Incan ruins, all with the blessing of Peru’s government.

Perhaps even more confounding, the Times article also has this claim,

“My great-grandfather, Mariano Ignacio Ferro, owned Machu Picchu when Hiram Bingham claimed to have discovered it, and even helped the American find his way there,” said Roxana Abrill Nuñez, a museum curator in Cusco who is waging a high-profile legal battle to be compensated for her family’s loss of Machu Picchu. She claims that the state expropriated the site from her family without payment.

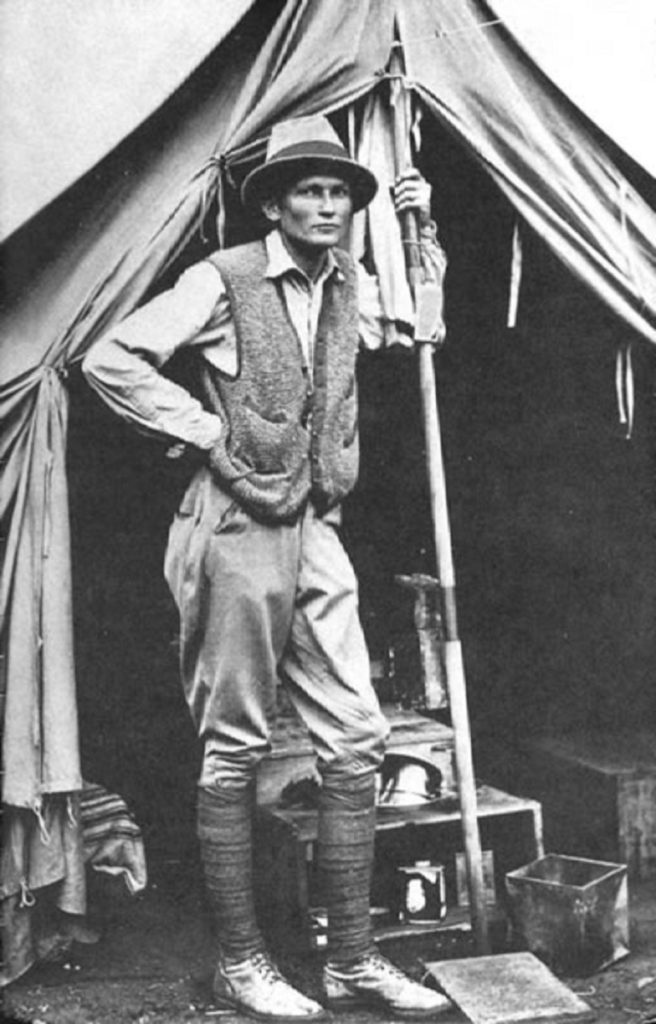

Still, it was Bingham, (seen here in this public domain photo from Wikipedia)

the Yale educated professor in South American history who recognized the historical and archaeological importance of the site even though it wasn’t the site he was seeking. Bingham’s purported goal was the city of Willkapampa (Vilkabamba) the last stronghold of the last Inka, Tupaq Amaru, who the Spanish executed in 1572 finally quashing the tattered remnants of the native empire that they had essentially defeated in 1532 when they executed Atahualpa. About 60 kilometers northwest of Machu Picchu, Willkapampa is considered by most to be the “Lost City of the Inkas.” Of this we can be certain, despite Bingham’s claims for nearly 50 years, Machu Picchu is not the “lost city.”

In something of an ironic twist, Bingham had actually uncovered ruins at Willkapampa on the same 1911 expedition that led him to Machu Picchu on 24 July. According to an article on National Geographic’s website, Bingham, “uncovered a few Inca-carved stone walls and bridges but dismissed the ruins and ultimately focused on Machu Picchu.”

[Photo of Bingham and guide from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

(Although it took until 1964, it fell to an adventurer named Gene Savoy to prove that a site that had been called Espiritu Pampa was, in fact, Willkapampa. Savoy would go on to uncover most of the known ruins.

Holding degrees in theology and divinity rather than history or archaeology, mainstream academics derided Savoy, his methods, and many of his out of left field assertions. For example, he claimed the Inkas and the great Mesoamerican civilizations communicated by sailing reed boats along the coast, that these ancient civilizations also sailed the open seas, that the jungle was at the heart of the ancient societies of South America, and that King Solomon acquired gold and precious stones from Perú.

Like Thor Heyerdahl, Savoy took matters into his own hands to confirm the possibility that these were seafaring civilizations. He built and sailed a totora reed boat he called Kuviqu – an acronym of Kukulkan, Viracocha, and Quetzalcoatl – more than 3,000 kilometers along the coasts of South and Central America. He also sailed a raft from Perù to Hawaii.

He had something of an obsession with a jungle culture of myth and legend called the Chachapoyas and later in life once said, “No sensible man goes down into the jungle unless he’s got something to follow. I see explorers as people with open minds who can scan many different sources for information, unconfined by an academic discipline, just like computers scan the internet. We’ve all learnt that the great thing is to follow the roads. Roads lead to ruins.”

In 1985 People Weekly described him as the real Indiana Jones.)

I’ll return to the story of Hiram Bingham and his “discovery” of Machu Picchu in the next post.