Although much about the early life of Héloïse d’Argenteuil (her “surname” is from the convent of Sainte Marie in Argenteuil where she spent much of her childhood and to which she would later return) has been lost to time, the same cannot be said of her adolescence and adulthood. She was probably born sometime in the last two or three years of the eleventh century or the very beginning of the twelfth and the circumstances of her upbringing have led some scholars to believe that she was the daughter of a nun.

While it’s not likely that Héloïse was Abélard’s intellectual equal (few people were) there can be little doubt that she was a precociously intelligent girl and would become a woman of great intellect. During her early education at the convent of Sainte Marie, she became fluent not only in Latin – the language of religion and scholarship – but in Greek and Hebrew as well. There’s evidence that as a teen, she achieved some recognition for her writing in the fields of grammar and rhetoric, the two other branches of classical philosophy.

Sometime around 1115, Héloïse moved from the convent to Paris to live with her uncle, Fulbert, who was the canon of Notre Dame Cathedral and who hoped to further her intellectual achievements. As for Abélard, he was struck with something like love at first sight. According to his own recounting he immediately determined he would seduce her.

[Héloïse imagined in a 19th century engraving – Wikipedia – Public Domain]

He began by suggesting to Fulbert that if the canon allowed him to move into his house he would happily privately tutor Héloïse. Abélard wrote in a memoir that soon after Fulbert accepted this arrangement, “more words of love than of our reading passed between us, and more kissing than teaching,”

Even at this early stage of their relationship, the pair evidently exchanged passionate letters. Little of their writing from this period survives though some letters from Héloïse that do exist portray intense passion and a certain equality of temperament and intellect. It’s reported that Abélard wrote love poems to Héloïse that were discovered, copied, and passed among his students thereby generating whispers of a secret romance between the pair that soon reached Fulbert who then evicted Abélard.

There was a small problem, though. Héloïse was pregnant. When she informed Abélard, he arranged for her to leave Paris to stay at his brother’s home in Brittany. Héloïse gave birth to a boy whom the couple named Astrolabe (possibly Astralabe) after a prominent scientific instrument of the time and who would be raised in Brittany by Abélard’s family.

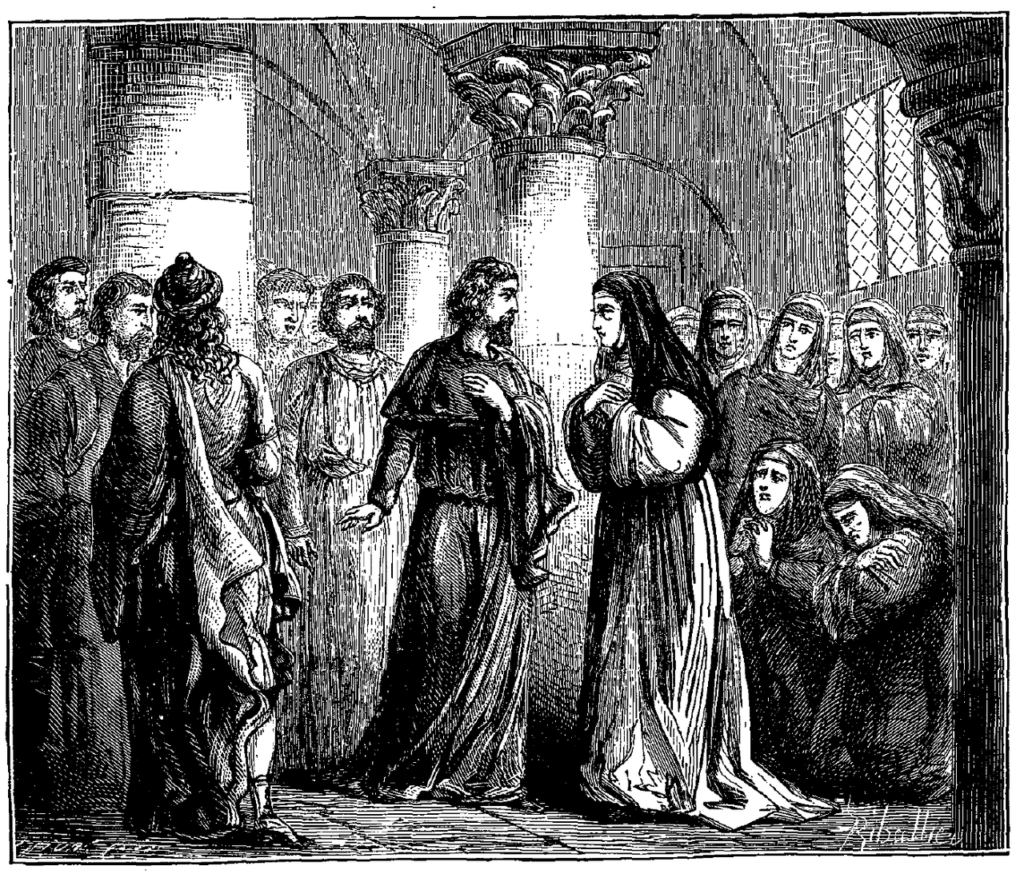

[Painting of “Abaelardus and Heloïse surprised by Master Fulbert”, by Jean Vignaud – 1819 – Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

Back in Paris, Abélard approached Fulbert and offered to marry Héloïse. Fulbert agreed but Héloïse demurred – though not because she thought it would harm Abélard’s career as master of the cathedral school or that family life was incompatible with the work of a philosopher – either of which might have been true. Héloïse had her own objections to marriage viewing it as a purely economic arrangement created to keep women subjugated. According to James Burge’s book Héloïse & Abélard: A New Biography, Héloïse wrote, “The name of wife may seem more sacred or more binding but sweeter for me will always be the word mistress, or, if you will permit me, that of concubine or whore.”

Ultimately, Abélard prevailed though Fulbert and Héloïse demanded the marriage be kept secret. Héloïse returned to live with her uncle and Abélard to his own lodgings. But rumors are hard to kill and after Héloïse denied the marriage, Abélard helped her leave Fulbert’s house and return to the convent at Argenteuil. Abélard paid dearly for this.

On the pretense that his family had been dishonored, Fulbert would exact a very specific revenge. Abélard wrote about the incident, “One night as I slept peacefully in an inner room in my lodgings, they bribed one of the servants to admit them and there took cruel vengeance on me of such an appalling barbarity as to shock the whole world.” He maintained that associates of Fulbert “cut off the parts of my body whereby I had committed the wrong of which they complained.”

After his recovery, Abélard entered the monastery at the Abbey of Saint Denis. It was there that he would write a treatise on the Holy Trinity titled the Theologia Summi Boni a rationalistic interpretation of Trinitarian Dogma that proved to be one more action that inflamed the passions of his enemies. Sometime during this period, Héloïse took her vows at Argenteuil.

Abélard left Saint Denis and settled in the area of Nogent-sur-Seine, in what is now the Aube district in northeast France. Eventually, he founded his own religious community, which he called the Oratory of the Paraclete which he left after a few years when he was elected abbot of Abbey of Saint Gildas in Brittany in 1125.

In Argenteuil, Héloïse had advanced to the position of prioress though there appears to have been a disagreement of some sort between her and the abbess. When a local bishop took possession of the Argenteuil property, Héloïse and the nuns loyal to her were evicted. Abélard then arranged for her to take over the Paraclete and some of the now homeless nuns followed her to Ferreux-Quincey where she established an order and became an abbess.

[1129 Etching “Abélard receives Héloïse at the monastery of Paraclete” – Wikimedia – Public Domain.]

The pair had barely communicated with one another for more than a decade until Abélard wrote his autobiographical Historia Calamitatum which he sent to Héloïse. She responded with a letter describing the events of their affair from her point of view and this set off a renewed correspondence between the one-time lovers. Those letters survived and not only added to their legendary affair but cemented it in the public’s imagination.

On 16 July 1141, at the instigation of Bernard of Clairvaux, Pope Innocent II excommunicated Abélard and his followers. Peter the Venerable, the abbot of Cluny where Abélard was then living intervened on his behalf and succeeded in having the sentence of excommunication lifted. Abélard died in April 1142 and was initially buried near the priory of Saint Marcel.

It’s said that Peter secretly exhumed Abélard from the grave at Saint Marcel, after which he personally brought his remains to the Paraclete and buried him under a table. It’s also said that on her death in 1164, Héloïse was buried beside him.

While Abélard is remembered for his philosophical writings and Héloïse earned a place in French literature both for her letters, which are considered foundational as a model for the classical epistolary style novel, and for her radical feminism, it is the pair’s love story that endures most tenaciously.

In Innocents Abroad, Mark Twain wrote,

But among the thousands and thousands of tombs in Père Lachaise, there is one that no man, no woman, no youth of either sex, ever passes by without stopping to examine. Every visitor has a sort of indistinct idea of the history of its dead and comprehends that homage is due there, but not one in twenty thousand clearly remembers the story of that tomb and its romantic occupants. This is the grave of Abelard and Heloise — a grave which has been more revered, more widely known, more written and sung about and wept over, for seven hundred years, than any other in Christendom save only that of the Saviour. All visitors linger pensively about it; all young people capture and carry away keepsakes and mementoes of it; all Parisian youths and maidens who are disappointed in love come there to bail out when they are full of tears; yea, many stricken lovers make pilgrimages to this shrine from distant provinces to weep and wail and “grit” their teeth over their heavy sorrows, and to purchase the sympathies of the chastened spirits of that tomb with offerings of immortelles and budding flowers. Go when you will, you find somebody snuffling over that tomb. Go when you will, you find it furnished with those bouquets and immortelles. Go when you will, you find a gravel-train from Marseilles arriving to supply the deficiencies caused by memento-cabbaging vandals whose affections have miscarried.