On the bus ride up rue de la Roquette David asked if we wanted to start at the top of the cemetery and walk down the hill or enter through the main gate and work our way up. We chose the former and entered by walking first east along Avenue Gambetta the south on rue de Rondeaux to the Gambetta Entrance.

(We rode on Bus # 69 which is possibly the best east-west sightseeing public bus ride in Paris. Its route begins on the Left Bank at Rapp-La Bourdonnais perhaps two blocks from the Eiffel Tower. It continues on la Rive Gauche past the Esplanade Invalides before crossing the Seine at Pont Royal where, if you’re so inclined, you can hop off into the Tuilleries Garden. If a visit to the Louvre is on your schedule, you can leave the bus at Quai François Mitterand or Pont-des-Arts . From the Birague stop it’s a very short walk to the Place des Vosges or you can continue east all the way up to Père-Lachaise.)

Of course, entering from the east would bring us into what I assumed was David’s least favorite area of the cemetery described in his book as “a deadening, dull grid.” On the other hand, we’d dispensed with the uphill part of the walk and would meet the older part of Père-Lachaise in a way that let us savor its spiritual closeness to pre-Haussman Paris by navigating the narrow pathways and roughly cobbled streets whose curves seemingly exist merely to delight in subverting symmetry.

It would be irresponsible of me not to note that entering through the Porte Gambetta is a choice I’d recommend only to those who have a guide like David Downie with them or who have come prepared with a map. (For me, even the maps that might or might not be available at the guard’s shack at the main entrance or one downloaded from the internet provide no guarantee that I’ll find any particular grave I’d like to see so I may have a particular bias on this point. Those of you who read my account of my adventure with Erin in Novodevichy Cemetery might recall that even with a map or guide, I have difficulty navigating cemeteries to find specific grave sites. I always enjoy my wanderings, nevertheless.)

David has lived in le Marais for more than three decades and, as I hope you gathered from my description of our morning walk, knows it intimately. He’s every bit as familiar with Père-Lachaise since, as he writes in Paris, Paris it, “happens to be about 150 yards as the raven flies from the office I rented for twenty years which is why I became a Père-Lachaise habitué.”

Entering from the east meant the first famous grave site we’d visit belonged to Oscar Wilde.

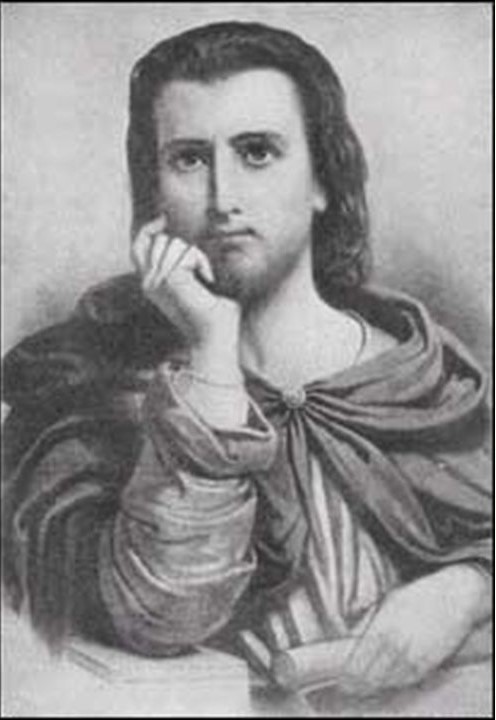

While the cemetery’s maintenance crew would likely have little objection to mementos or tributes left by visitors, at many grave sites in Père-Lachaise – particularly those belonging to people who have become in some way iconic – there has been a rather sad tendency to mar or deface their memorials or headstones. Wilde was one of those people and this is what the monument might have looked like without the plexiglass barricade.

(I failed to note the site I used to download this photo. Sorry.)

(Sometime during our walk, David provided another bit of sage advice when he urged us to visit Montmartre – which we’d planned for Saturday – as early as possible telling us that even at the beginning of May by 10:30 the crowds would feel stifling. Here I’ll also remind you that another of the joys – at least for me – of having a guide like David was spending a day with someone who relates to puns as adeptly and enthusiastically as I. Patricia and Alison, I think, found that aspect of our day far less enjoyable.)

I didn’t note the time of our arrival at Oscar Wilde’s tomb but I suspect it was sometime around 14:00. The cemetery closes at 18:00 and while four hours might seem like ample time to walk through a cemetery, keep in mind the 44-hectare size of this city of the dead and, among other attractions, the lengthy list of notables interred therein.

In fact, we’d been traversing Père-Lachaise bounding from grave to grave with David also directing our attention to some of his favorite art, (As is almost universally the case in such cemeteries, some of the tombs are, indeed, works of art.) We’d paid little regard to the time when the sound of bells permeated even the far-flung corners of the funerary grounds. In this cemetery, the guards use the bells to round up the visitors and usher them out and by the time the bells peal, four of the five entrances have been sealed and everyone is shuttled toward the Porte Principale or Main Gate. I note this because the method seemed more appropriate, more charming, and certainly more French than having someone blare an announcement over bullhorns or loudspeakers.

One of the other advantages of having a guide like David is the chance to see the tombs of some fascinating but perhaps lesser-known individuals. In the coming posts, I’m going to introduce you to six whose stories I think you’ll enjoy. Before I get to those, since I’m again breaking chronology, let me return to the story of Abélard and Héloïse.

An Innocent Abroad.

Although he’s never asked me when I’ve been a guest on his radio show, my buddy Bruce Posner likes asking people about the first concert they ever saw. For me, it was a fabulous show at the long defunct Painters Mill Music Fair outside my hometown of Baltimore when I saw the incomparable Ella Fitzgerald and Oscar Peterson on one thrilling night. I can’t tell you if Ella sang the Cole Porter standard Just One of Those Things that night but I can tell you that it was hearing her sing that tune (perhaps on a record or possibly during one of the other times I saw her live) that I first heard of Abélard and Héloïse.

When she sang the verse, I had some idea who Dorothy Parker was and I definitely knew Columbus and Isabelle, and Juliet and Romeo. But Abélard and Héloïse was a new pair of names to my adolescent ears. So, I learned something of their story. And what a story it was.

Even had he not had his famous and doomed affair with Héloïse d’Argenteuil, even if their remarkable letters had not survived, students of philosophy would certainly know the name of Pierre Abélard who is considered by many to be the preeminent philosopher of the 12th century and the father of nominalism.

Abélard was a child of minor nobility born in Le Pallet, France in 1079. His keen mind became apparent at a very early age and by the time he was 13 he had renounced his inheritance and began a nearly single-minded pursuit of philosophical and theological education.

He spent the following decade studying under two of the era’s most famous scholars Roscelin de Compiègne (better known by his Latinized name Rucelinus) and Guilliaume de Champeaux. However, his intellect and, more pointedly, his ego quickly outstripped those of his teachers and he established his first school at Melun in 1102 under the patronage of Étienne de Garlande.

When Guilliaume resigned his positions as archdeacon of Paris and master of Notre Dame, Abélard, after studying for several years with Anselm de Laon, returned to Paris where he assumed Guilliaume’s former position as Master of Notre Dame and Canon of Sens in 1113. Abélard again began teaching and he drew a number of students away from Anselm but in such a contentious way that the disputes would carry on for years and eventually result in Abélard’s excommunication.

In the next post you can read a brief biography of Héloïse d’Argenteuil and their tragic affair.