Eliel had a son.

Though he started by designing small things, Eliel’s son Eero, whose name alone should be very familiar to those of us who regularly complete (or attempt to complete) crossword puzzles, made even more iconic contributions to the American building scape than his father. Eero was born in Finland in 1910 and, although he came to the U S at age 13 with his family, he can still be legitimately claimed as a Finn.

Eero first worked with the famous furniture designer Charles Eames and the two won an award for their design of the “Tulip Chair.” Some of Eero’s subsequent furniture designs such as the Womb Chair can be seen at the Brooklyn Museum.

Among the better known major works the younger Saarinen also designed are the TWA flight center at JFK Airport in New York and the main terminal building at Dulles Airport – some 40 kilometers west of Washington, DC and my departure point for this trip. However, his most iconic structure, completed in 1965, has become emblematic of the city in which it was built. This structure rises 192 meters above the park known as the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in Saint Louis. We call it the Gateway Arch. So, even if you didn’t know his name, you probably know his work.

Adjacent to the train station is a large square limned by two buildings of note. I might have visited one of them had I believed I had sufficient time. The first is the Finnish National Theater which is the oldest Finnish speaking professional theater in the country – housing a troupe dating from 1872. This edifice, which became the Theater’s permanent home and was completed in 1902, is an example of the national romanticist design that Saarinen had originally planned for the railway station.

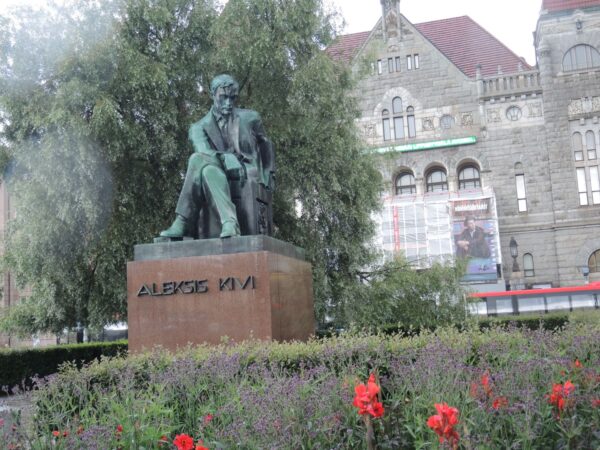

A statue of Alexis Kivi graces the front of the theater. Kivi (and yes, I had to research this) wrote 12 plays and a collection of poetry but his most famous work is said to be a novel called Seven Brothers. He died in 1872 at age 38 having lived during the period of Russian rule over Finland. He would have been about 11 years old when the Kalevala was published so he came of age when expressions of Finnish nationalism were cresting. As a participant in that tide, he’s celebrated for being among the first and greatest writers to write in Finnish rather than in Swedish, which was the preferred language for intellectual Finland at the time, or in Russian, which was, of course, the language of the ruling power.

Across the square, and covered in even more scaffolding than you see in front of the Theater, is one of the buildings of the Finnish National Gallery – the Ateneum. (Like all of the Nordic countries, Finland has a very short construction season so cranes and scaffolding are common July sights.) The bulk of the art displayed in the Ateneum is Finnish and spans styles and periods from 18th century rococo portraiture to some of the more experimental art movements of the 20th century. One interesting note is that in 1903 the museum acquired the painting Street in Auvers-sur-Oise by Vincent Van Gogh. Why interesting, you wonder? Interesting because, with this acquisition, it became the world’s first museum to own a Van Gogh painting.

Unfortunately, my time in Helsinki is, like my body as I age, growing shorter and I thought a visit to the Ateneum unwise. Instead, with the rain slowly becoming intermittent, I decided to simply wander about a bit and try to enjoy some of the varied architecture that characterizes this city while generally heading back toward the harbor. (Here again is a link to the photos from the afternoon.)

For better or worse, my walk wouldn’t include the area known as Merihaka because, although it doesn’t appear to be too far, if I’m reading the map correctly (and this is not always a certainty), it’s in the opposite direction of where I ultimately need to go. Merihaka, as I understood it from briefly reading about Helsinki, is an architecturally controversial neighborhood in the city because it typifies the concrete block functionality characteristic of the 1970s.

I returned to the Senate Square to shoot some additional photos but also made certain to take another walk along the Esplanadi to finish my photographic day (or so I thought) at another famous Helsinki landmark, the Havis Amanda Fountain. The story of Havis Amanda, like the Sibelius monument, exemplifies how people’s perception of art changes over time.

The statue was originally cast in 1906 by Ville Vallgren a Finn living in Paris. His model was a 19-year-old Parisienne. She was installed in her granite fountain in her present location in 1908. Vallgren intended the vision of the mermaid rising from the water to represent the birth of Helsinki. In the fountain, she’s surrounded by four seals as she stands on a bed of seaweed in a rather languorous pose intended to evoke a farewell to the water.

She was unveiled to some controversy. In 1906, Finland, with its own Diet, though not independent, had been the second country in the world to introduce universal suffrage (New Zealand was the first in 1893) and some thought the depiction of a nude woman (not to mention a nude French woman), on a pedestal in what some saw as a seductive pose was little more than a belittling sexual objectification of women. Over time, though, attitudes began to change (Surprise!) and the Finns came to tolerate her. Then they began to see her more along the lines of Vallgren’s intent as representative of the city’s spirit. Today, many consider her the most beautiful and important artwork in Helsinki.

She has also become the object of an important annual Helsinki ritual and tradition. The Finns celebrate the first of May as the beginning of spring. Every year, students from local high schools and universities perform an elaborate ceremony during which they put a graduation cap on the statue. Our guide told us that this is quite the spectacle.

The day was late and, though the weather was finally beginning to break, I felt I had time only to begin to trudge back to the ship thinking I would have liked at least another day in the Finnish capital. As I passed the Market Square, something caught my eye. I rushed over to confirm the reality of what I’d seen. An hour before my departure and 36 hours before I’d walk through the door of my home in Silver Spring, I’d spotted the lone element needed to provide a sense of completion to this trip. The one missing piece, turtles!

Back in Stockholm.

I have one final anecdote before wrapping up my account of this year’s journey and it happened Saturday morning on the ride from the ferry to the airport. Our travel company had arranged the transfer and our driver (I was riding to the airport with Jeff – one of the people in the group who’d been on the tour since Copenhagen.), it turned out, also worked part time as a guide. She asked us if she could answer any questions about Stockholm that may have held over from our first brief sojourn there.

I asked her about the cenotaph of Birger Jarl outside the city hall and mentioned my disappointment in having missed the opportunity to visit the cemetery at Solna. She told us Birger Jarl’s story and the tale of why his remains were never moved to Stockholm but she really took my breath away when she told me that not only was her mother buried in the cemetery at Solna but that her grave was just a few steps from Nobel’s gravesite and that it would be visible from the highway. She slowed a bit as we passed the spot and, with her direction, I was able to glimpse the small monument marking Nobel’s grave.

Although she shared many more interesting facts with us about Sweden, I listened politely and absorbed little of it as I tried to shift into the appropriate mindset to endure the upcoming stretch of 14 or 15 hours in airports, airplanes, and vans after spending the previous 16 hours or so on the ferry from Helsinki.

Those of you who have been with me since the beginning, have visited five countries, traveled for three weeks, endured my puns, and plowed through essays totaling more than 37,000 words. I hope you’ve enjoyed sharing the journey.

To Helsinki, thanks for the turtles and Go Terps!