Morning has broken

Viennese Overture.

How delightful it was to slip on my Crocs, walk down one floor to the breakfast room and discover a large tray of lox beside the usual breakfast fare. Technically, it was simply smoked salmon but that was close enough for me to be in breakfast heaven for the next few days. While I was gobbling down my breakfast a woman came over to my table and asked if I was Todd from the Earthbound Expeditions group. I told her I was, indeed. She introduced herself as Betty and said she and her husband Bob had recognized me from our pre-trip Zoom meetings.

We chatted a bit about our respective plans for the day – mine was to start by visiting two cemeteries – Saint Marx and Zentralfriedhof with no plans beyond that. I told them I’d look forward to seeing them again at dinner and we went our separate ways. (Confession: Since remembering names isn’t one of my strengths, I was a bit relieved that I’d have an easy mnemonic to remember the names of at least two of the 10 people who’d be joining the group. I’d just gotten out of bed and was eating breakfast so the memory tie was Bed & Breakfast = B&B = Betty and Bob.)

GPS – Confounding Conundrum.

My first objective this Saturday morning was to visit Friedhof Wien Saint Marx (Saint Mark’s Cemetery) and, while it turned out to be unexpectedly beautiful and interesting, in this instance my purpose was to visit a specific grave – that of W A Mozart. But first, I have a bit of a GPS rant.

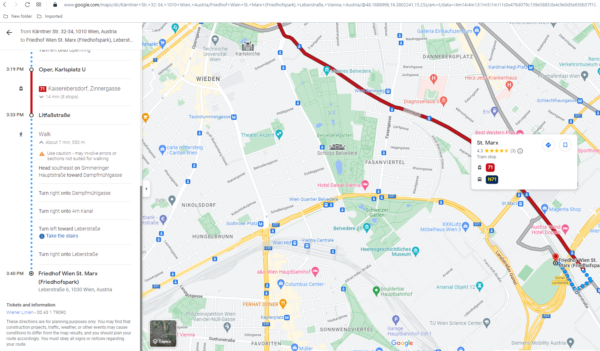

Long before reaching Vienna I’d looked at the distance from my hotel to Saint Marx and at nearly four kilometers judged it farther than I wanted to walk. However, I saw that I could take a tram that left a much shorter walk. Here’s what the GPS wanted me to do starting with taking the #71 tram to Litfaßstraße then circling back to walk to Saint Marx. As you can see, there’s actually a stop on the tram line called Saint Marx and, when I saw that, I wondered if it wouldn’t be easier to use that stop. It was. I don’t recall how I managed to trick the GPS into depositing me at the Saint Marx stop but not only did I need to make merely one right and one left turn but there were signs pointing to the cemetery. I think the Litfaßstraße stop was some 75 meters closer to the cemetery. But, the option I chose required two turns rather than four or five proposed by the GPS. To me, when it comes to directions, always choose simplicity.

Mozart myth busting (1) – not a pauper’s grave.

I’ll start with this: It’s true that no one knows Mozart’s actual burial spot. It’s known that he was buried in Saint Marx but the actual spot isn’t known for several reasons. However, one of them is not that he was buried in a mass pauper’s grave although certainly when he died he had amassed a significant amount of debt.

Substantial mystery and misreporting surrounds Mozart’s death and burial and it’s certainly not my intent to provide a definitive portrayal of those events. However, I hope to dispel some of the myths starting with the notion that Mozart was buried in a mass grave. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians reports, “Mozart was buried in a common grave, in accordance with contemporary Viennese custom, at the Saint Marx Cemetery outside the city on 7 December.”

The term common grave distinguishes the site from an aristocratic grave nothing more.

While it’s possible that the composer’s original burial site was dug adjacent to two or three others buried at the same time, it’s much more likely that it was an individual burial. The principal differences between the two grave types are that aristocrats were more likely to have permanent markers while common graves were marked with a simple wooden cross – if they were marked at all. Of greater importance is that graves of aristocrats were permanently sited while the city of Vienna had the right to relocate the graves of commoners after 10 years thereby allowing them to reuse the original site. This is almost certainly what happened with Mozart. As Robert Wilde wrote on thoughtco,

Grave space was at a premium, a problem local councils still have to worry about, and people were given one grave for a few years, then moved to an all-purpose smaller area. This was not done because anyone in the graves was poor.

Mozart myth busting (2) – a dark and stormy night.

Mozart died shortly after midnight on 5 December 1791. One of the first accounts of Mozart’s death appeared in the Bayreuther Zeitung on the 17th of that month:

Vienna, 6 December.

Music has suffered an irreplaceable loss: Herr Mozart, the artist and darling of our age, surrendered up this past night his beautiful, harmonious spirit, and now mixes his heavenly tones with the choir of the immortals. He died too soon for his family and for art, to which he would have offered many more monuments of his abilities.

Note that the dateline is 6 December. It appears that this report was taken from the Wiener Zeitung published the day after the composer died. More than half a century later on 28 January 1856, Joseph Deiner wrote in the Vienna Morgen-Post:.

The night of Mozart’s death was dark and stormy; at the funeral, too, it began to rage and storm. Rain and snow fell at the same time, as if Nature wanted to shew [sic] her anger with the great composer’s contemporaries, who had turned out extremely sparsely for his burial. Only a few friends and three women accompanied the corpse. Mozart’s wife was not present. These few people with their umbrellas stood round the bier, which was then taken via the Grosse Schullerstrasse to the Saint Marx Cemetery. As the storm grew ever more violent, even these few friends determined to turn back at the Stuben Gate…

The accuracy of his description is undermined by the weather records of the Vienna Observatory for 6 December 1791 – the day between Mozart’s death and funeral as Wikipedia reports, “The Vienna Observatory kept weather records and recorded for 6 December a temperature ranging from 37.9 to 38.8 degrees Fahrenheit (2.8 °C – 3.8 °C), with “a weak east wind at all … times of the day.” The likelihood of a calm day bookended by two unreported stormy days seems implausible.

Seeing his “few friends turn back at the Stuben Gate” (Stubentor) is possible but geographically unlikely. There was a funeral mass held at Saint Stephen’s Church with the arrangements likely made by Mozart’s friend and supporter Baron Gottfried Van Swieten and possibly his student Franz Sussmayer. Passing through Stubentor is a possible route but not necessarily the most direct one and is less than a fifth of the way. For the weather to turn them back so quickly would indicate an extremely severe and unreported storm.

One possible source for all this melodrama was Mozart’s widow, Constanze. Trying to raise the seven year old Karl Thomas and the seven month old Franz Xaver, the shrewd Constanze had to manage her way out of the debt that Wolfgang had left behind – something she did quite successfully.

Marking a spot.

In the mid nineteenth century the Viennese made an effort to identify the most likely site for Mozart’s burial in Saint Marx and in 1859 erected a memorial stone designed by Hanns Gasser. This was later moved to the Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery) which would be my next stop. A stone slab was placed in SaintMarx to identify the grave’s location and the stone angel and column seen in the photo

were added later. (In fact, this, too is not original. It was damaged during World War II and had restorations performed in 1950 and 2016.)

A final gesture.

Before leaving Saint Marx to continue my journey to Zentralfriedhof, I placed two items on the memorial – a stone and a pine cone. Since antiquity, the pine cone has symbolized human enlightenment, eternal life, and regeneration and seemed a fitting tribute to make to Mozart.

As for the stone, it remains part of my Jewish cultural identity. One explanation behind the reason Jews leave stones is the close relationship between the Hebrew words for pebble and bind. The memorial prayer called El Maleh Rachamim contains the phrase btz’ror Ha-chayim meaning to be bound in the bond of life. Leaving a stone shows that the individual’s memory continues to live on both in and through us. That, for me, is certainly true of Mozart.

Next stop, the not at all central, Central Cemetery.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026