Some technical specifications.

There was not great uniformity in the Inkan road system. For example, not all of the roads were paved with stone but those of importance such as at the main gate of Machu Picchu almost always were. As they did with much of their other construction, the Inkas often shaped the road to the contours of the local geography. To date, the widest road – about 15 meters – has been found at Huánaco Pampa which is an Inkan archaeological site some 350 kilometers northeast of Lima. Others, such as those following mountain ledges might be as narrow as a meter though they were typically between one and four meters wide. You can see this along this stretch of the trail to Machu Picchu.

[Inka road from Wikimedia Commons by Martin St. Amant.]

Looking at that photo you can also see that geography didn’t daunt the Inkan engineers. They built their roads to hug the sides of mountains or cross ravines, rivers, deserts, and 5,000-meter-high mountain passes with equal aplomb. Examine the picture above closely and you’ll notice that these roads included bridges and stairways as the terrain demanded. Since these routes were intended only to accommodate travelers on foot who might have sometimes been accompanied by nimble climbing llamas, the Inkas could build their roads to follow the most direct paths between destinations. This might not have been possible had they relied on the wheel or massive beasts of burden.

If the directness of the road above isn’t evidence enough, look at the road called Carreterra Hiram Bingham that our bus followed from Aguas Calientes up the mountain and compare it with the dotted lines marked Camino Inca on this satellite image from Google Maps. For the Inka, no serpentine ascent was necessary.

Think of the map of the Inkan road system I included in this post after we’d crossed from Bolivia into Perú and had passed the literal acme of the journey and you might recall two main north-south highways. The coastal route started in Tumbes close to Perú’s current border with Ecuador. It mainly followed the coast until it turned east toward Arequipa before ending in present day Santiago. The mountain route began a bit northeast of Quito and followed a path through the mountains to Cusco, around Lake Titikaka, through western Bolivia and Argentina before ending near Mendoza. A network of secondary highways connected the two.

I’ve also written elsewhere about the clear delineation between the rainy and dry seasons (at least before the impact of global climate change). The Inkas were certainly aware of this weather pattern and had to find ways to meet the challenge of maintaining their roads in the face of flooding that frequently occurred in valleys of the Andes during the wet season.

One solution avoided the issue altogether by building roads so high up on the mountain sides they’d be unaffected. This wasn’t always possible or practical so another approach used small stone walls and a sophisticated system with frequent drains and culverts to channel rainwater along or under the road. Roads that crossed wetlands were usually buttressed or even built on causeways.

Perhaps equally impressive are the Inkan bridges. Built using stone, reeds, or ropes woven from native grasses, the bridges were important enough for the Sapa Inka to appoint a Chaka Suyuyuq or Governor of the Bridges who inspected them annually.

You can watch a group of local people maintain the bridge building tradition with the bridge at Q’eswachaka in the video below. (Note that it’s a suspension bridge – a bridge built without towers or piers – and is supported solely by anchors at each end. Although common today, this type of bridge was unknown in Europe at the time of the Inkas.)

The Chaski Express – not quite Western Union or UPS but still fast.

The use of the road system is believed to have been generally limited to the elite or those on official administrative or judicial business. However, because some roads were constructed outside their territory, there’s some indication that the road system might also have served as a trade route or possibly had a military purpose. The roads were also the routes for the chaski.

Chaski were runners who carried messages between population centers. Sometimes they toted perishable goods such as fresh fish for the table of the Sapa Inka and others in the nobility. It’s said that collectively the runners could cover as much as 250 kilometers per day. (This seems remarkable particularly when framed against the famed Pony Express. That service, that launched in 1860 with its horses, special mailbags, and riders limited to weighing no more than 125 pounds or 57 kilos covered an average of only 320 kilometers per day.)

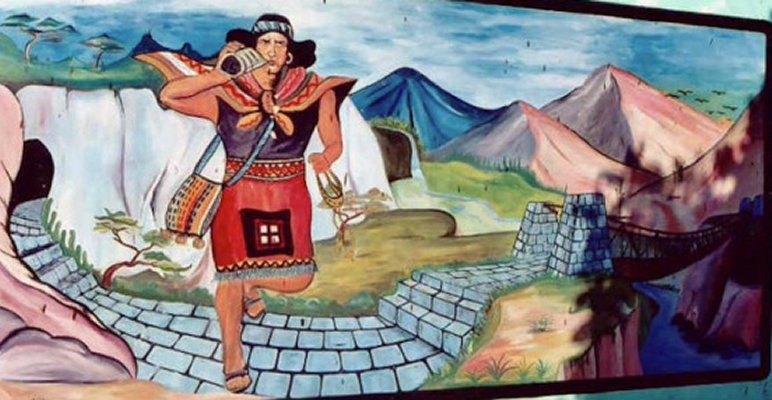

The basic Inkan unit of measurement for their road system was the topo which was a distance equivalent to about seven kilometers. In what was effectively an extended relay race, each chaski would run approximately one topo (though some sources say they ran less than half that distance). As he approached a chaski wasi (or messenger’s house) he would presage his arrival by blowing into a conch shell. He would then quickly transmit his message or hand his parcel to the next runner who would repeat the process until reaching the final destination. (Noble travelers along the Inka roads might find more comfortable accommodations called tambos spread every three to five topos.)

Chaksi always ran alone not only because of the speed required but also because the importance of their role afforded them special protection guaranteed by the Sapa Inka.

[Illustration of a Chaski – Source: Ancientpages.]

Their safety was so secure that they neither had guards nor carried weapons, either of which would have likely slowed their progress. But this also came with a price. It was critical to the runners that they transmit their messages accurately – particularly those going to the Sapa Inka. If the Sapa Inka learned that a message was inaccurate, it meant a severe punishment at best and execution at worst.

So how, you might wonder, did the runners assure the accuracy of their messages? For the answer to this we must look to the mysterious khipu. But that discussion is for the next post.