Les Nymphéas (Water Lilies).

I promised a closer look at the eight paintings in the Water Lilies series in L’Orangerie so here it is for those among you who are interested. Let’s begin with their display.

Each room has four panels with each panel being two meters high and a bit more than 11 meters long. Monet once said the paintings were meant to create, “the refuge of a peaceful meditation in the center of a flowering aquarium.”

(It blew my mind when I saw I’d gotten this picture with no one in it!)

Given the general reverence with which the paintings are viewed today, it might surprise you to learn that this wasn’t always true. By the time Monet was working on the Water Lilies series in the 1910’s and 1920’s, the impressionist movement that he had seeded in the 1860’s had long since cross-pollinated with new ideas germinating new blooms of artistic efflorescence. The Symbolism of Gaugin, the Neo-Impressionism of painters like Seurat, the Expressionism of Munch and Kandinsky, and the early 20th-century Cubism of Picasso and Braque could all trace their roots to Impression, soleil levant.

Monet began developing cataracts in 1911 and the condition became severe enough that he underwent surgery to remove them in 1923. Critics looked at much of the work he produced after 1910 and simply called the paintings messy. Some art writers rather brashly suggested they were more about blurred vision than creative vision.

They pointed to his color palette and the general reddish tone of his pre-surgery paintings, dismissing his argument that his depiction of flora, water, and light was an artistic choice. (In fact, after his surgery, which broadened his visible spectrum, Monet repainted some of the Water Lilies series with more blue than they originally had.) Still, perhaps seen as something of a relic, the now venerated series was initially met with critical disdain.

Although the Orangerie had the eight paintings on display from its opening in 1927, the Water Lilies series was, for the most part, ignored for at least the first 20 years after the painter’s death. Many of the 250 surviving paintings (Monet reportedly destroyed at least 15 in the series in 1908 just before they were scheduled to be exhibited.) sat in storage in his Giverny studio. Then, the rise of abstract expressionism in the 1940’s prompted some curators to look at Monet’s work with fresh eyes.

Over time, the Water Lilies series became increasingly focused on the surface of the water leading the artist to paint what he called “aquatic landscapes.” As the series progresses, the edges of his pond move ever closer to the edges of the frame eventually moving beyond those edges until he had cut out the horizon altogether. From that point, the works became a study of water and the way it reflects light and the world above it.

This renewed look at his work led curators, critics, and art historians to credit him with having fertilized yet another burst of creativity in his contemporaries and inspiring yet another hybrid movement. By 1955, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York had purchased their first painting from the Water Lilies series and it wasn’t long before it was one of the museum’s most popular paintings.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that those mid-20th century curators were right in taking a fresh look at the artistry behind the paintings. Les Nymphéas had indeed shattered Impressionism’s standard view. And this includes works that are less monumental than those on view in the Orangerie. Ann Temkin, a curator at MoMA wrote,

In early Impressionism you had these views of nature where you were out looking at a seaside or out looking at a field and there were markers of location that you could understand, ‘Here I am as a person. Here’s the view that the painter is portraying for me.’ With the Water Lily panels, he’s changed it completely so that rather than you being larger than the view that you’re looking at on an easel-sized canvas, somehow you have become immersed in the scene of this water lily pond. All the normal markers, like the edge of the water or the sky or the distant trees, have disappeared, and you’re just right in the face of those water lilies and the surface of the water with the clouds reflected from above you become lost in this expanse of water and of light.

One last concert.

It had been a long day with lots of walking and while the day hadn’t been particularly hot, we both required a breather when we returned to our flat for a cool drink, a splash of water on our faces, and, perhaps, a wee snooze. Feeling refreshed, we set out for our dinner and concert.

As we’d walked about the neighborhood Thursday afternoon, we’d noticed a poster board outside Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis church promoting a concert featuring Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Pachelbel’s Canon, and sacred songs. We were able to buy tickets at the door for the 20:30 show and then had to find a place to have supper.

It’s at this point where two critical aspects of the restaurant we chose – Café La Favorite – came in to play. First, it offers “service continu” or continuous service. (Remember that we had to wait when we arrived for dinner at Le Temps des Cerises because many – if not most – French kitchens don’t open for dinner until 20:00 and with a 20:30 concert looming, this wasn’t going to work for us.) Service continu means that if the restaurant is open, the kitchen is open.

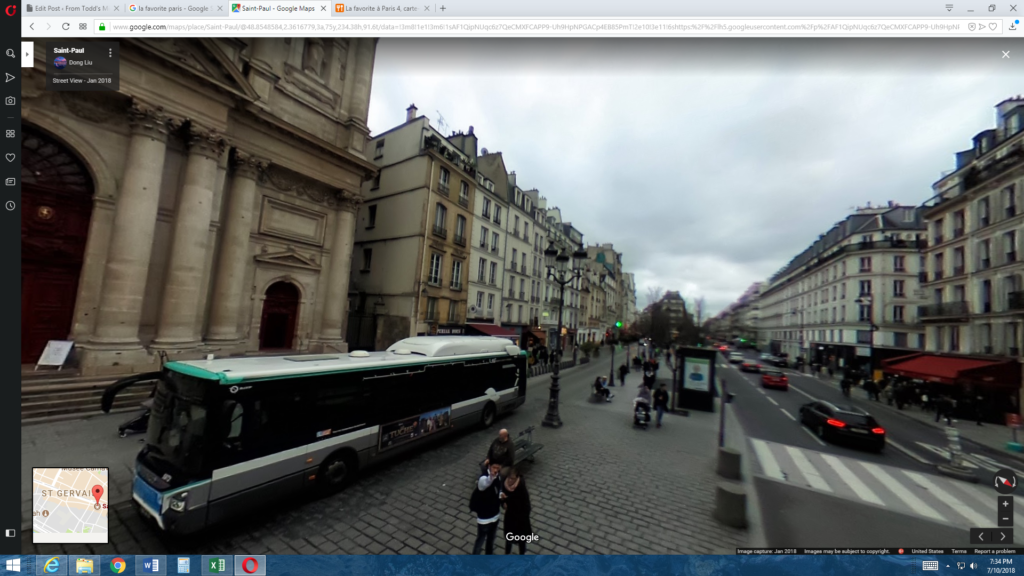

La Favorite also had the advantage of proximity. In this street view photo from Google maps,

the church is on the left behind the bus and the red awning on the right is the Café La Favorite meaning we were literally steps away from the concert venue. As for the meal, I’d describe it as acceptable though so underwhelmingly ordinary that, even looking at a photo of the menu I can’t recall what I ate. It’s possible I had a salad. It’s equally possible I had one of the reduced calorie dishes or I could have had pizza. I simply can’t remember.

We finished our meal early enough that we were near the head of the queue as people began lining up outside the church. Once the line had grown to 25 or 30 people, a number of heavily armed police officers took up positions in front of the church doors. I peered down the line and, seeing very few people who looked significantly younger than I and some who looked older, I commented that I couldn’t imagine what sort of security threat a group of sexa or septuagenarians waiting to attend a baroque chamber music concert could pose. Someone opined that the officers were there for our protection. My reaction was similar to seeing the soldiers on the streets of Rouen. It didn’t make me feel any better. Or safer for that matter.

The performers were the Alegria Orchestra with Jean-Philippe Kuzma directing and serving as lead and solo violin. The vocalist was Anara Khassenova. While the acoustics were better here than they had been at the American Church where we’d met Jie, the church is certainly no concert hall. Astonishingly, I was able to find a very short clip on You Tube of the Orchestra playing the Four Seasons at Saint-Paul.

Fortunately, we didn’t need perfect acoustics to enjoy the first rate performances and it was a lovely way to end a long day. When the concert ended, we made the short walk to return to the flat and, with that, I bid you good night.