Bairro Alto and Chiado are such close neighbors that I had no notion of when Ana and I crossed out of one and into the other. As I learned when I returned to the U S, they are so close that many guides couple the two – although the Metro joins Chiado with Baixa. In some ways, it might be fair to call Chiado simultaneously the oldest but also among the newest of Lisbon’s neighborhoods.

The Romans.

In a previous post I noted that Neolithic people had settled on the west coast of Portugal some 10,000 years BP. It’s possible they established small communities in the area of Lisbon but no evidence has yet been uncovered. Similarly, while little evidence remains today and the hill hadn’t yet received its toponym, Romans were among the earliest residents of Chiado – land they would have chosen because it was agriculturally fertile. In fact, the area was mainly agricultural through the middle ages including the time of the ouster of the Moorish Muslims from the west coast of Portugal (AKA the Reconquista) by Afonso Henriques who, as you now know, became Portugal’s first king in the twelfth century.

Over the next two centuries, several convents were established in Chiado – the first being the Saint Francis Convent in 1217. However, time took its toll and only the Convento do Carmo (which Ana and I would pass later in our walk) remains. And, because of the 1755 earthquake,

it’s a mere shell of its former self.

In keeping with my express desire to avoid an ABC (Another Bloody Church/Another Bloody Castle) tour of Lisbon, Ana also merely pointed out the Igreja de São Roque as we walked passed it leaving the viewpoint at Alcantâra. It’s importance lies in being the first Jesuit Church in Portugal and in the attached Chapel of Saint John the Baptist that was commissioned in 1740 by King João V said to be the most expensive chapel in Europe.

We also walked by the Casa do Ferreira das Tabuletas a spectacular 1863 building covered in tiles that represent Earth, Water, Science, Agriculture, Commerce, and Industry with the Eye of god at the top.

The neighborhood has a deep historical connection with Portuguese literature. In fact, one source of the hill’s toponym is said to have originated with the street poet António Ribeiro who, because of his wheezing and squeaky voice was known as Chiado. Ribeiro was a satirical poet who lived in the 16th century and was a contemporary of Luis de Camões considered by some to be Portugal’s greatest writer. Both writers are honored with statues. Camões has a square of his own while Ribeiro has his statue on the Largo do Chiado

near another important Chiado landmark – A Brasileira.

However, there’s another explanation for the name that I think is at least equally likely. Competing claims to the throne between the two sons of King João VI – the absolutist Miguel and the liberal constitutionalist Pedro who was also the emperor of Brazil – culminated in Dom Pedro’s victory after a six year civil war that began in 1828 and ended with the Battle of Asseiceira on 16 May 1834. Within weeks, one of Pedro’s top ministers, Joaquim António de Aguiar, issued a decree that terminated the state sanction of masculine religious orders thereby nationalizing the lands and possessions of over 500 monasteries.

Although few farmers could afford to purchase the land, as had been the hope and intent of the government, the monasteries had to become self-sufficient and began growing crops to bring to market. It’s said that the wheezing horses and squeaking wheels of their wagons alerted neighborhood grocers to their approach thus providing the name Chiado.

And then there was the earthquake.

Earthquakes occasionally impact the Portuguese mainland with the most recent major temblor being a 7.8 magnitude quake centered in the Gulf of Cadiz on 28 February 1969. The Wikipedia page reports that, “The resulting damage killed thirteen people (11 in Morocco and 2 in Portugal). Damage to local buildings was “moderate”, according to the United States Geological Survey. Overall, structures were prepared for the earthquake and responded well, sustaining slight, if any, damage.” (Emphasis mine.)

In a way, not only Lisbon but all of Portugal had been preparing for a major earthquake for more than two centuries in part because of the aftermath of the quake – with an estimated magnitude between 7.7 and 9.0 – and tsunami that struck on 1 November 1755 devastating much of the country, destroying 85 percent of Lisbon’s buildings, and killing between 12,000 and 50,000 of the city’s 200,000 inhabitants.

[Image from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

It’s arguable that no single natural disaster has had a greater impact on a society than the 1755 earthquake had on the Portuguese. It’s echoes reverberate still today not merely in the preservation of the Convento do Carmo that serves as a physical reminder of the destruction but also philosophically, economically, and politically.

Philosophically: Because it happened on All Saints Day, the disaster engendered debates about divine judgment and rippled through European Age of Enlightenment intelligentsia.

Economically: A 2009 study estimated that the disaster cost Portugal between 32 and 48 percent of its GDP but also allowed for a partial decoupling of its interdependence with Great Britain.

Politically: It saw the consolidation of power held by Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal. (If you recall the neighborhood map from the previous post, you might remember an area called Avenida – Marquês de Pombal and while I’ve mentioned his name before, it’s time to learn more about him.)

Pombal, the son of a country squire who had secretly married a nobleman’s niece, was already serving as prime minister to King José the First when the earthquake struck. He emerged as the main figure in the country’s rebuilding efforts. Prior to becoming PM, he’d served as ambassador to Great Britain and Austria under King João V and received his appointment as prime minister when José succeeded his father in 1750. By bringing Enlightenment ideas including economic and political reform from other parts of Europe, Pombal was viewed as an estrangeirado by the entrenched nobility.

[Marquis de Pombal from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Fortunately for Portugal, Pombal proved to be practical, brilliant, and perspicaciously inquisitive. Asked what to do in the quake’s immediate aftermath, his first response was reportedly, “bury the dead and heal the living.” (Unfortunately for many, he was also ruthless in persecuting his enemies or critics.) You can read a bit about him here.

His plans to heal the living turned out to be remarkable. He convinced the king to accept the most costly alternative proposed by the kingdom’s chief engineer – one that included totally razing the Baixa quarter. Pombal oversaw the rebuilding plans drawn up by the chief engineer Manuel da Maia and military engineers Eugénio dos Santos and Elias Sebastian Pope.

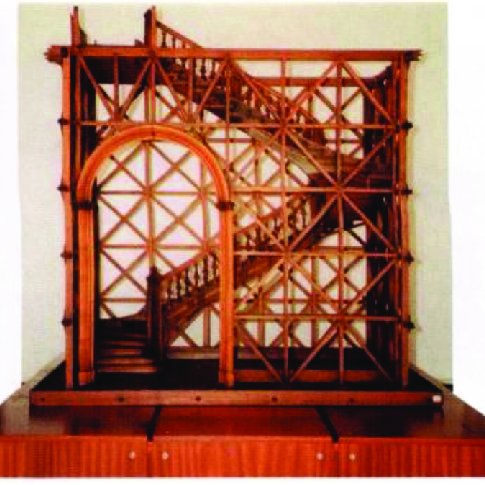

The four men introduced a style of building known as Pombaline. In addition to very specific features for the facades, it more importantly introduced an early anti-seismic design feature that used a flexible wooden structure known as the Pombaline cage implanted within the walls, floors, and roofs so buildings would shake but not fall.

[Image from Researchgate.]

These were then covered using pre-manufactured building materials in an early example of applying prefabricated building methods.

But Pombal wasn’t done yet. He ordered a questionnaire sent to all parishes of the country regarding the earthquake and its effects. The responses, which remain in Portugal’s national archive, not only allowed modern scientists to reconstruct the events, but earned Pombal a place as the forefather of modern seismology.

Then, on 25 August 1988.

For the ensuing two centuries, newspapers flourished and, thanks to cafés such as A Brasileira, Chiado became home to some of Portugal’s most famous writers and artists. One might meet historian and novelist Alexandre Herculano, Eça de Queirós, or Fernando Pessoa – who is honored with a statue outside the café. The café

opened a 1925 exhibition of eleven canvases of young Portuguese artists could thus also be called Lisbon’s first museum of modern art.

Then, came the night of 25 August 1988. The opening paragraph of the Washington Post story read, “Flames swept through Lisbon’s historic Chiado district today, devastating much of the 10-block commercial and literary heart of the capital. One person was killed and 43 were injured, officials said.”

The scene looked like this (from researchgate).

For many, the Chiado fire is considered the worst disaster to strike the city since the 1755 earthquake. Some buildings from the 18th century survived and a few others were renovated by the Portuguese architect Siza Vieira. But much of Chiado had to rebuild again. In the process it became for some a sophisticated district of theaters and bookshops, of art nouveau jewelry shops, and international luxury retailers. For others, Chiado is simply a place you go to sip coffee at a café before a night of partying in Bairro Alto.

Now you know a little of the oldest and newest of Lisbon’s neighborhoods but there’s one more important date we need to discuss before we go down the hill to Baixa and Ana takes her leave.