It seems almost impossible that the current world champion could have arrived in Lillehammer virtually unnoticed by the press covering the Olympic women’s figure skating competition but such was the case for Oksana Baiul the 16 year old wonderchild from Ukraine who had burst onto the scene a year earlier when she finished second at the European Championship and then, despite a fall in training that left her with herniated disks in her back and neck, followed that performance by winning the gold medal at the World Championship in Prague barely two months later.

The little girl from Dnipropetrovsk.

Oksana Baiul was born in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine on 16 November 1977. When she was two years old, her parents divorced and, excepting one brief encounter, she wouldn’t see her father again until she was 25. Raised in a small apartment by her mother and grandparents her mother wanted her to study ballet. However, Oksana was

a bit of a chubby child so her grandfather purchased her a pair of used ice skates hoping the the exercise would help her fitness. For Baiul, who once said, “I think I could skate before I could walk,” it was love at first ice.

Baiul not only loved the ice but almost immediately displayed preternatural ability. By age five she had begun serious training to be a competitive figure skater studying with Stanislav Koritek, a prominent Ukrainian coach. She won her first competition at age seven.

At this young age, Baiul’s entire support system centered on her mother, grandparents, and coach. When she was 10, that support began to unravel. It began with her grandmother’s death followed a year later by her grandfather’s. Soon thereafter, her mother Marina was diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

Perhaps sensing her impending death, Marina began pushing her daughter to train even harder telling her that she had to be able to take care of herself. By age 13, Oksana was an orphan. Although her father came to the funeral, the two apparently didn’t speak.

Seeing the struggles of the now orphaned girl, Koritek took her under his wing and Baiul lived with him in Dnipro for a time. Then, in 1991, Koritek left Ukraine for what he’d told everyone was a vacation. In fact, the real purpose of his trip to Canada was to secure a new job and better opportunity. Barely 13 years old, Baiul now had no one.

Trying to help the young skating prodigy, skating officials in Dnipro reached out to two well known Ukrainian coaches Galina Zmievskaya and Valentyn Nikolaev. Zmievskaya was a prominent coach who had trained Viktor Petrenko who’d won the Olympic gold medal in 1992. Recognizing Baiul’s talent and perhaps moved by the orphan’s story, Zmievskaya agreed to coach her without getting paid. Baiul, with no other choice, left the only home she had known and moved nearly 500 kilometers to Odessa where she lived in an athletic dormitory, went to school, and began rigorous training under Nikolaev and Zmievskaya.

But even then the situation wasn’t easy. Although she now had some support from her coaches and from Petrenko who was still working with Zmievskaya, the former Soviet Union had broken apart and Ukraine was now an impoverished independent state. In fact, the facilities available to Baiul and her fellow skaters were so underfunded that the skaters themselves had to maintain the ice which was often rutted and bumpy.

The world should have been paying attention.

On the second week of January 1993, figure skaters from all over Europe descended on the Helsinki Ice Hall in the capital of Finland for five days of competition that would determine the European Champions. Among the women was a hitherto unknown 15 year old from Ukraine, Oksana Baiul. In third place after the short program, Baiul’s elegant and daring long program lifted her past Germany’s Marina Kielmann into the silver medal spot behind Frenchwoman and two-time defending champion Surya Bonaly.

Baiul then returned to Ukraine to begin training for the World Championships in Prague two months later. During this time she suffered an unreported back and neck injury. Although somewhat better known after her finish in Helsinki, the favorites entering that competition were Bonaly and the reigning American queen of the ice, Nancy Kerrigan.

Baiul was in second place after the short program though this time she trailed Kerrigan who would falter in the free skate and finish fifth. Once again the dynamic, powerful, and graceful 15 year old who Brian Boitano at the time described as “the most talented skater ever,” dazzled in her long program and became the youngest world champion since Norwegian Sonia Henie won her first title at age 14 in 1927.

But then 6 January happened.

Let me clear up immediately that in this instance I’m talking about 6 January 1994. It just so happens that 6 January was the date that Shane Stant assaulted Nancy Kerrigan in Detroit. In addition to the expected coverage by sports oriented publications, a slew of media from outlets like People magazine and The National Enquirer descended on Lillehammer with all their attention focused on the drama between Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding even though the part Harding had played in the assault remained unclear at the time.

With so many eyes turned elsewhere, Baiul was able to go about her business – training in an under the radar sort of way. Then came the night of the short program. As had been the case at the World Championship the previous year, Kerrigan led with Baiul second. Harding had essentially skated herself out of any medal contention by finishing the short program in tenth place.

Zmievskaya urged Baiul not to practice on the day off between the short program and the free skate, but the headstrong teen who felt insecure everywhere but on the ice decided to practice against her coach’s wishes. The result was nearly disastrous. Baiul collided with another skater and gashed her leg to the point of needing stitches and aggravated the spinal injury she’d suffered the previous year while training for Prague.

(Before I wrap up the story, any young readers need to know that in 1994 most of America was connected to television mostly through the over the air networks of ABC, CBS, and NBC. ESPN and CNN were barely 15 years old and FOX TV was a mere eight. It was, literally the first year of the internet. I tell you this because you should be impressed when I tell you that the 1994 Olympic Women’s Figure Skating competition drew what was then the largest rating for any sporting event in American history. In fact, it was the fourth highest rated broadcast of any sort behind only the final episode of “M*A*S*H”, the last episode of “Roots”, and the “Who Shot J R” episode of “Dallas”.)

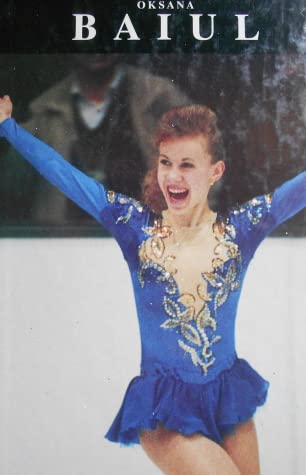

It seemed like the drama had drawn the attention of the entire world and unlike her disappointing performance at the World Championship the previous year, Kerrigan’s free skate in Lillehammer was nearly perfect. It looked as though she had the gold in hand. Then Baiul did this:.

Sportswriter Christine Brennan said, “She gave the performance of her life. I don’t think anyone who was there will ever forget it.”

The unchoreographed triple jump near the end of her program likely secured her the title. In the closest finish in any Olympic women’s figure skating competition to that point in time, the Ukrainian orphan overcame her injury and her personal demons and won gold by one tenth of a point on a single judge’s card. And with that, sixteen year old Oksana Baiul became the first gold medalist from the newly sovereign nation of Ukraine.