After we’d finished picturing Wolfgang, Constanze, and young Karl Thomas spending their days and nights in the flat at Domgasse 5, our guide Martha took us to a few other points of interest in Vienna’s first district. First we passed the Gothic and Romanesque Saint Stephen’s Cathedral that is certainly among Vienna’s most important churches and one of its most iconic landmarks. Given that it was a short walk from the hotel along Kärtnerstrasse to Stephansplatz, I had seen the church Saturday but hadn’t walked behind it and seen the unfinished portion.

From there it was a short few hundred meters to the pedestrian street called Graben to see its memorable centerpiece the Wiener Pestsäule or Vienna Plague column. My friends at Atlas Obscura describe it thus: “…the huge gilded, baroque confection of a sculpture at its center is in fact a memorial to the worst plague in Viennese history.” To me, calling it a “confection of a sculpture” is overly kind.

Like the Marriage Fountain at Hoher Markt, the original Pestsäule began life as a wooden monument built in 1679 to ward off the plague that was ravaging Vienna. Just before departing for Prague, the then Emperor Leopold the First committed himself to erecting a more permanent marker once the epidemic ended. (Leaving town didn’t help as the plague followed him to Prague landing there in 1681.) When the column’s first designer, Matthias Rauchmiller died in 1686 before much progress was made, several people became involved with the design and I think it shows.

For me, it roused memories of the monument to Peter the Great in the Moscva River near the Krymskiy Bridge that I called in my post about that day, “certainly the ugliest statue in Moscow and perhaps in all of Russia.”

From there we walked past the much more visually appealing Hofburg Palace on our way to Schreyvogelgasse 16 – the Beethoven Pasqualatihaus – one of the Vienna residences of Ludwig von Beethoven.

The peripatetic rock star.

I’ll admit that calling Beethoven a rock star might be a bit overly modern but there can be no doubt that he was as famous and adored as any resident of early 19th century Vienna. Hoping to study with Mozart, Beethoven, who had himself been considered a child prodigy, first came to Vienna in 1787 when he was 16 or 17. His hopes were dashed when within weeks he received word of his mother’s grave illness and returned to Bonn. (Reports vary as to whether these two giants of musical composition ever met.)

He didn’t return to Vienna until 1792 several months after Mozart had died. However, once there, he lived in the area for the ensuing 35 years until his death in 1827. His funeral service was held at the Church of the Holy Trinity more commonly called Alserkirche (referred to in the citation below as Minorite).

[Minorite Church from Wikimedia Commons by User Funke BY CC-SA 4.0].

The website Visiting Vienna provides this contemporary description:.

A report in the April 12th, 1827 edition of the Wiener Theater-Zeitung noted (my amateur translation and interpretation of the annoyingly-hard-to-read font):

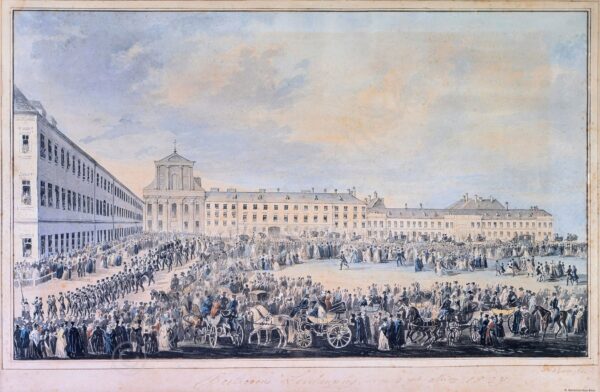

The funeral of one of the most extraordinary men of our times took place on Thursday, March 29th. It was the famous composer, Ludwig van Beethoven, a true Alcides of music, whose earthly remains were to be taken to their final resting place, and the lively participation of learned individuals from all parts of society held the promise of a large crowd to witness the journey. At 3pm, the funeral cortege collected both in and outside the apartment of the deceased in the Schwarzspanierhaus in the Alservorstadt, and the procession left at 3.15pm.

The artistic elite of the imperial city carried and surrounded the coffin…some 15,000 people from all parts of society accompanied the remains of this genius of a composer on his last journey…the crowd was such that the trip from the apartment to the Minorite church (a distance of just a couple of hundred steps) took an entire hour.

[Beethoven’s Funeral by Franz Xavier Stöber from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

You might recall the previous post mentioning that Mozart had at least a dozen different residences in and around Vienna. Beethoven also had frequent address changes and the Beethoven Pasqualatihaus we were about to visit was one of at least six different homes he had in and around Vienna. His apartment was on the fourth floor of this building

and he had two long periods of occupancy first from 1804 to 1808 and again from 1810-1814. There’s some question regarding whether Beethoven actually occupied the rooms that are open to the public. When this building became part of the Vienna Museum, the consensus was that Beethoven occupied rooms on the opposite side of the floor and that the current museum is more a reproduction and memorial. However, some recent research has indicated that the entire fourth floor was a single apartment and thus, we might have actually walked in Beethoven’s footsteps.

Beethoven resided in a number of other places that I was unable to see or visit and one that I was. I didn’t see his apartment at the then newly constructed Theater an de Wien where Emmanuel Schikaneder hired him as the director of music and resident composer, the house at Grinzingerstrasse 64 where he lived in 1808 with 18 year old Franz Grillparzer (who went on to become one of Austria’s best known poets and writers and who wrote a eulogy for Beethoven’s funeral), the house at the winery Mayer on Pfarrplatz where he lived briefly in 1817, the building at Laimgrubengasse 22 where he lived in an apartment that faced the courtyard from October 1822 to March 1823, nor the house in a small apartment with a courtyard at Probusgasse 6 in Heiligenstadt (then a suburb) where he first went in 1802 hoping to slow his increasing hearing loss. This building is now a part of the Beethoven Museum and is where he wrote the famed Heiligenstadt Testament – a letter to his brothers that he never sent and that was discovered after his death in 1827.

The letter from the then 32 year old Beethoven begins,

O ye men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the cause of my seeming so. From childhood my heart and mind was disposed to the gentle feeling of good will. I was ever eager to accomplish great deeds, but reflect now that for six years I have been in a hopeless case, made worse by ignorant doctors, yearly betrayed in the hope of getting better, finally forced to face the prospect of a permanent malady whose cure will take years or even prove impossible.

I did, on the day following this tour, walk past the building at Schwarzspanierstraße 15 where I took this photo

marking the place of Beethoven’s death.

As it is with Mozart, Beethoven’s cause of death is a matter of frequent debate with no fewer than six possible causes – alcoholic cirrhosis, syphilis, infectious hepatitis, lead poisoning, sarcoidosis, and Whipple’s disease – have all been suggested. It seems that three people were present when he died – his brother Johann’s wife, his secretary Karl Holz, and his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner who provided the only contemporary written report. There’s no real mystery about the last documented words he spoke. When told that his publisher had sent him 12 bottles of wine, Beethoven said, “Pity, pity. Too late!”

In addition to the cause of death, the other great mystery arising from that time centers on a passionate love letter addressed to his “Immortal Beloved.” It began, “My angel, my everything, my very self…” The movie of the same title speculates that his object of desire was his sister-in-law Johanna and that his nephew Karl was actually his son. There’s no evidence to support this claim and to date, the identity of Beethoven’s Immortal Beloved remains a mystery.

One door, two movies.

Just before taking us to a group lunch, our guide Martha pointed to a door in a building close to the Beethoven Pasqualatihaus and noted that the doorway marks the first appearance of Orson Wells in the movie The Third Man. (You can see the screen capture in the photo album I linked in yesterday’s post.) The sharp-eyed will also spot the doorway in the now classic romance Before Sunrise. Of course, I could likely point to a long list of the spots that Céline (Julie Delpy) and Jesse (Ethan Hawke) pass on their day and night in Vienna on 16 June 1994 but since the site Visiting Vienna does such a thorough job, I needn’t duplicate their efforts.

The next post will take you to a pair of utterly unique spots in the Austrian capital.

“alcoholic cirrhosis, syphilis, infectious hepatitis, lead poisoning, sarcoidosis, and Whipple’s disease”

After looking up the last two, the last three seem to be a bit far fetched. I know paint had lead in it back then but still wouldn’t put money on it…and I would rule out syphilis because it usually causes dementia at the end and by your description of his last words, he had his faculties…

Cirrhosis or hepatitis are the most plausible in my opinion.

As I was writing this, it almost seemed like it would be easier to make a list of what it wasn’t. ??