The first promise.

I promised I’d circle back to the importance of the Spanish name for the Tower and now it’s time for me to do just that. It’s also the section where I’ll return, as I promised in this post, to a connection to rue Saint-Jacques.

The opening sentence of the Wikipedia entry on its Christian pilgrimage page reads, “Christianity has a strong tradition of pilgrimages, both to sites relevant to the New Testament narrative (especially in the Holy Land) and to sites associated with later saints or miracles.” I’ve read that while the fundamental teachings of Christianity point to no one place as being holier than any other, the tradition of the pilgrimage to sites closely associated with the life of Jesus dates back to the earliest days of the religion.

Over time, this rather egalitarian view of geography, buttressed by the increased difficulty faced in reaching Jerusalem and its environs, made pilgrimages to other sites – those associated with saints and miracles – a more practical religious journey and, by the Middle-Ages, these shorter treks were far more common than pilgrimages to the perceived Holy Land. One of those shrines is the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela a town in Galicia in northeastern Spain. To reach the cathedral, pilgrims follow El Camino de Santiago de Compostela or The Way of Saint James. (In French this would be le Chemin de Saint Jacques de Compostelle.)

According to one legend, after Jesus’ death, Saint James the Greater traveled to Iberia to spread the gospel but, after spending some indeterminate number of years there and meeting with only limited success, he returned to Jerusalem where Herod had him beheaded. Two of his followers placed him in a boat that was “guided by angels back to Iberia” where it washed ashore near Fisterra in northern Spain. Local villagers are said to have buried his body in a “nearby forest.” Apparently, they carried the remains some 80 kilometers inland – or if they buried it in a nearby forest the remains somehow moved that far inland on their own – because 800 years later a body was discovered by a hermit and declared by the Bishop of Iberia to be the remains of Saint James. A small church was erected to mark the spot that became Santiago de Compostela and soon thereafter the pilgrimages began.

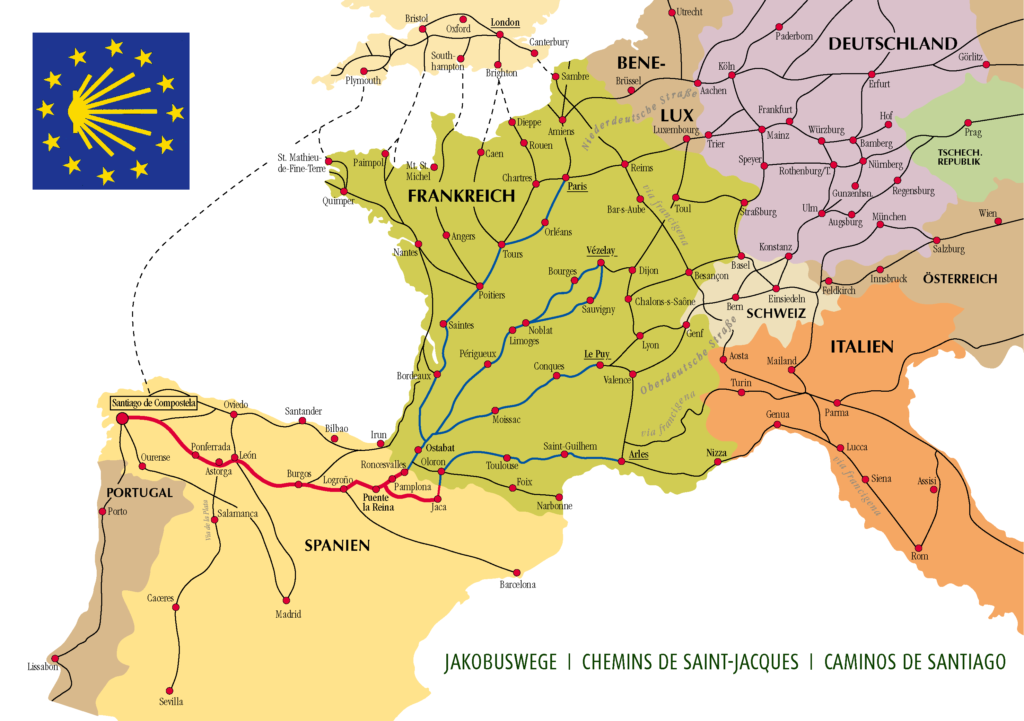

The traditional route of the Camino crosses northern Spain

[Map by Manfred Zentgraf, Volkach, Germany from Wikipedia Commons.]

and the most common starting point for pilgrims wanting to walk the entire length of the Camino is Roncesvalles in Spain. In France, pilgrims generally consider the starting point to be Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. It’s about 25 kilometers from there through the Pyrenees to Roncesvalles and another 800 kilometers to Santiago. (Those who wish to take the most traditional route will either turn north from Roncesvalles or start closer to the coast along the Bay of Biscay in Irun or Bilbao to find the Camino Primitivo {Original Way} which starts in Oviedo.)

As you can see from the map, the journey can begin nearly anywhere in Europe and all (save the boat from Plymouth) pass through France. The four French routes appear in blue on the map. They are, from south to north:

- The via Tolosana or Chemin d’Arles (the Latin Tolosana is because it passes through Toulouse). This is the only French route that doesn’t join the Camino Frances at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

- The via Podiensis or Route du Puy starting in Le Puy.

- The via Lemovicensis, or Route Vézelay leaving from Vézelay (the Latin refers to passing through Limoges).

- The via Turonensis, leaving from Paris, passing through Tours.

The French routes have all been modified because modern roadways have blocked or paved over many of the traditional historic paths. However, in France there are the dual systems of Grandes Randonnées (Great Hikes) and Grandes Randonnées du Pays (Great Country Hikes) using waymarked often small farm roads to keep pilgrims safe. (Those associated with The Way of Saint James are marked with GR65.) Of course, the route that concerns us at the moment is the one passing through Paris – the via Turonensis.

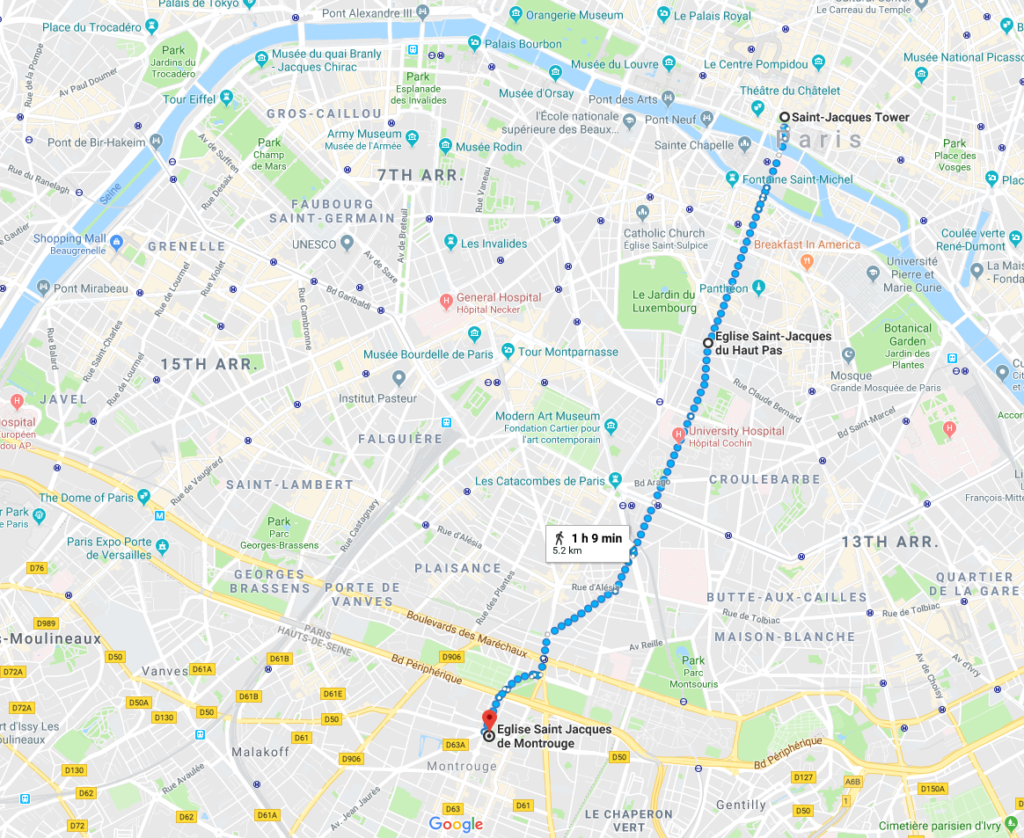

Beginning in the 16th century, when pilgrims met in Paris to begin their walk along the via Turonensis, the traditional meeting point was none other than the Tour Saint-Jacques where Patricia and I walked after breakfast. From there, they would begin the journey south and east along the oldest street in Paris – rue Saint-Jacques (which Pat and I happened upon on our first post cruise walk). Today, if you are so inclined,

you can walk the first five kilometers of The Way beginning at the Tower, crossing the Seine on the Pont Notre-Dame, across the Île-de-la-Cité onto the Rive Gauche, and continuing along rue Saint-Jacques. To keep you on the path, you follow not the Yellow Brick Road but the scallop shell.

(The first association of scallop shell symbolism with the apostle James the Greater is based on his lineage as the son of Zebedee a Galilean fisherman. When he appears in art, he typically wears a pilgrim’s broad-brimmed hat and has a wallet or water-gourd hanging from his staff or his shoulder. The scallop shell appears on his hat, his cloak or on the wallet.)

Whether in France or in Spain, whether cement or ceramic, brass or glass, painted on traffic signs, or embedded into roads or buildings, whether realistic or abstract, simple or complex design, scallop shell markers along the Camino reassure participants that they have not taken a wrong turn.

In my post describing the day of our return to Paris I noted that we didn’t see the oldest tree in the city which stands in a park beside the Église Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre (Church of Saint Julian the Poor). However, you Pilgrim, will find your first scallop at the holy water font just inside the doors of that church. Continue along rue Saint-Jacques and soon after you see the dome of the Pantheon to your left, you observe a sign noting that you are passing through the Porte Saint Jacques one of the southern gates in Philippe-Auguste’s wall. You’ll see another scallop ahead of you at the Église Saint-Jacques du Haut Pas (Saint James of the High Pass {I think}).

Look closely at the church wall and you’ll spot the shell you seek. Or stop in the church for a drink where you’ll find another scallop shell holy water font. Continue far enough along the path (now called rue Faubourg Saint-Jacques) and in the 21st-century you’ll reach the Boulevard Périphérique a limited access high speed ring road that girds Paris at its city limits. With some imagination one can view the Périph – as the Parisians call it – as a modern analogue to the wall built by Philippe-Auguste.

Find your way across the highway and look for the Église Saint-Jacques le Majeur (Church of Saint James the Greater) in Montrouge. The earliest record of a church in this location dates to the 13th century but the current structure was built in the 1930’s. In its stained glass windows you will spot your scallop shells.

[Photo from ECMH.fr].

Patricia and I did not make this walk and all of the descriptions above are based on my research on le Chemin in Paris. One other fact I learned in that research is that in 1885, the bishop of Paris declared that the church at this location was one of three in the Paris region to which people could make a pilgrimage if they were not capable of walking all the way to Santiago de Compostela. If you are capable and you’d like to complete the walk from here, your journey has a mere 2,000 kilometers remaining.

The second promise.

Before I return to what remains of Pat’s and my last day in Paris, I also promised you another connection to rue saint-Jacques. This is that connection.

The gentleman in this photo is Juan Carlos. I met him when I spent a week in Spain in October 2017 volunteering for Vaughan Town. The picture was taken in April 2018 as he was making his pilgrimage along the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. (In yet another thin connective thread, Jane, one of the Anglos from that week, also walked a stretch of the Camino in late July or August this year but I don’t have a photo of her doing so.)

Coming up, a few more encounters of a repetitious kind.