Among the first things I learned after boarding the van taking our small group on a tour of Bruny Island was that the state of Tasmania isn’t simply the main island. Lutruwita is but the largest of more than 300 islands in the archipelago that comprises the Tasmanian state. Today, I’d be crossing to one of those smaller islands. It was called Lunawanna (or Lunawuni) by the Nuenonne People and is identified as Bruny Island on most maps.

Initially, the European name for the island was spelled Bruni drawing its name from the French Explorer Bruni D’Entrecasteaux who explored the area in 1792. The Island Council adopted the present spelling in 1918.

I acknowledge that I am on the land of the Nuenonne People. I acknowledge their custodianship. The Dreaming is still living. From the past, in the present, into the future. Forever. I would also like to pay respect to the Elders past, present, and emerging and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present.

Not your traditional morning tea

We boarded the ferry at Kettering and crossed the D’Entrecasteaux Channel to Roberts Point. Although we had some lovely views on this cloudy morning crossing – including looking back a Kettering

we didn’t see any of the Australian Fur Seals or Little Blue Penguins that are said to populate the channel. I think we needed about an hour and a half from Hobart’s CBD to our first Bruny Island stop to pick up the Bruny Island Oysters that would be part of our “morning tea.” I, of course, loved the name of the vendor.

As you can see from the photo below, the day was beginning to clear but was still a little chilly as we sampled the oysters, a pair of local cheeses, and had hot beverages to drink.

We’d left Hobart at about 07:40 and needed about two hours to reach this little picnic spot across the isthmus that joins the northern and southern sections of the island and which, given the time of year, had me singing, “I’ll be home for isthmus” if quietly and to myself. And, if you’re wondering, no, ten in the morning isn’t to early to eat cheese, bread, and fresh raw oysters.

There’s a light

We made a stop or two on the way to the next highlight moment of the day – a tour of the Cape Bruny Lighthouse. While GPS technology has generally replaced lighthouses in the 21st century, their importance through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries can’t be understated.

Likely prompted by the wreck of the convict transport ship George III in which 134 people died, Governor George Arthur commissioned the construction of the lighthouse in 1835. (More than 400 shipwrecks had been reported in and around the rough and dangerous waters encircling Tasmania.) It was built by convicts using locally quarried dolerite and first lit in March 1838 becoming Australia’s third or fourth operating lighthouse.

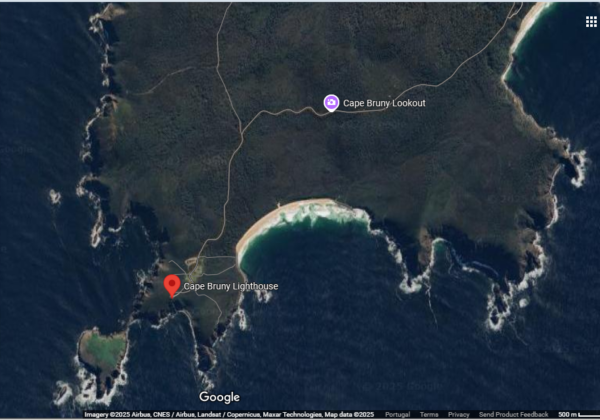

As you can see from this satellite view from Google maps, the lighthouse is quite isolated

and the task of keeping it functioning – as it was with any lighthouse – was particularly demanding. Seventy-four and a half hectares surrounding the lighthouse were set aside as a reserve to provide the first superintendent, William Baudinet, and his three convict assistants with essential timber, vegetable gardens, and grazing land. In the early days of its operation, communication with Hobart came either by sea or by a long rough track to North Bruny Island while supplies were delivered to a jetty 5km away at Great Taylors Bay.

Supplies were critical because not only must a lighthouse be kept lit but its light must be visible far enough out to see to be identified meaning the glass must be kept clean and clear. The website Cape Bruny Lighthouse notes,

Each lighthouse had a unique light characteristic which was ensured by a clockwork planetary table requiring rewinding every eight hours but rewound about every hour routinely to help the keepers stay awake. The fifteen lamps of the original 1838 Wilkins lantern each burned 600mls of expensive sperm whale oil per hour and needed frequent refilling. The lamps were extremely fragile, being replaced every three nights in 1839.

Because Craig Parsey is the managing director of both the lighthouse and the tour company that operated this excursion, we were treated to a personal tour of the facility that’s currently Australia’s second oldest, southernmost, and longest continually staffed extant lighthouse.

Everyone on the tour climbed the spiral staircase

and stepped outside for some terrific views. I was particularly fascinated by the dolerite.

Connections

We humans tend to be creatures of habit. Even in a small van with 10 or so passengers, once we’ve settled on our chosen seat, that’s where we tend to stay. Thus it was that each time we left the bus, we generally returned to the same seat when we reboarded. Our next stop was at the Hotel Bruny for lunch where I had Pepper Calamari and a locally brewed Cherry-Apple cider. By the time we’d finished lunch and were a bit more than halfway through our day long tour, I’d had the pleasure of sitting next to L for several hours and would continue to do so for the duration.

I’m not particularly adept at this but I’d place her as being in her late twenties or early thirties. The child of Vietnamese refugees, she was born in Germany and currently living and working as an accountant in Sydney. Chatting with her certainly made the time on the bus pass more pleasantly and quickly.

We had several more tasting stops including at Bruny Island Chocolate (one of many chocolate “factories” on this small island) and at Bruny Island Honey for a honey tasting. Since we would both be spending a few more days in Hobart, by days end we’d connected through WhatsApp. (For those old enough to remember, that’s WhatsApp, not.)

Truganini

(But I know there is no other way)

Our last stop for the day was along the isthmus locally called The Neck that separated Adventure Bay on the east from the sheltered Isthmus Bay on its west side. It’s also home to the Truganini Lookout and Rookery.

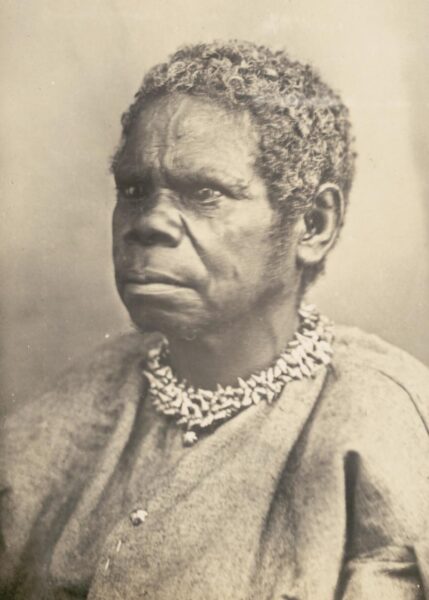

The British arrived in Tasmania in 1803 and Truganini, the daughter of Manganerer an elder of the Nuenonne people was born on Lunawanna about a decade later. Before she turned 15, she’d witnessed the murders of her mother, uncle, and betrothed as well as the abduction of her two sisters. At about this time, she met George Augustus Robinson who was trying to implement his “Friendly Mission.”

Seeing her people killed and dying from diseases for which they had no resistance or treatment, she agreed to help Robinson based on his promises that if they relocated to Flinders Island, they would be safe from violence and away from disease. He also at least hinted that the Palawa would eventually be able to return to their Country. She traveled with Robinson for six years helping him to convince the Palawa that this plan would be their salvation. As we learned, Robinson’s promises were empty words. The Palawa continued dying on Flinders Island and when the last of them were removed to Oyster cove, Truganini was among them.

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

She was also among the last four survivors and, in 1874, moved to Hobart where she died two years later. She is sometimes cited as the last pure blood Tasmanian Aboriginal. (This isn’t the case. Some of the Palawa had retreated into the bush and remained free on the main island.)

What transpired after her death is yet another indication of the maltreatment of Australia’s Indigenous People. She had asked to be cremated with her ashes spread across D’Entrecasteaux Channel. Instead, she was buried at the Female Factory in South Hobart but after only two years her body was exhumed by the Royal Society of Tasmania and displayed in the Tasmanian Museum until 1951. It was only then, some 75 years after her death (a longer time than she lived) that her remains finally received her desired cremation.

A few words about supper

My choice for supper was an odd one. I ate at The Ball & Chain Restaurant on Salamanca Place. Why an odd choice you ask? The answer is that it’s primarily a steak house and I don’t eat beef (or any mammals as a rule). However, I wanted to experience the building which was originally called Haig’s Store. Constructed by convicts over a period of 18 months beginning in 1830 it was among Governor Arthur’s major reclamation projects. I had a ceviche which was only salmon with capers and whatever side vegetable dish was available that night with a Cascade Lager.

By the time I walked back to my hotel at 20:30 or so, it seemed the entire town of Hobart had retired before I would. It seemed odd for a Friday night.

The next post has a surprise in store for you and me but for now, you’ll have to be satisfied with today’s photos.