It had been a fun day thus far but these morning activities were merely the preliminaries. After lunch we’d drive 20 minutes south and come to the site of the main event – the Pinnacles Desert in Nambung National Park. As nearly as I can tell, the Juat People applied the term Nambung, meaning crooked or winding, to the seasonal river flowing through the national park and to the broader area that includes the Pinnacles Desert. (Of course, I’d happily accept any corrections or additional information as long as it has evidentiary support.)

What the geologists say about the Pinnacles

Anyone who has seen the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon or the striking landforms in Monument Valley might be a bit underwhelmed by the formations in the Pinnacles. While the tallest of these formations is said to reach about five meters, they are generally small.

What becomes impressive as you walk through them is their varied shapes and their sheer numbers. This section of Nambung Park covers about 190 hectares and while there are gaps between the clusters, it’s hard to understand how widely spread they are until you’re there.

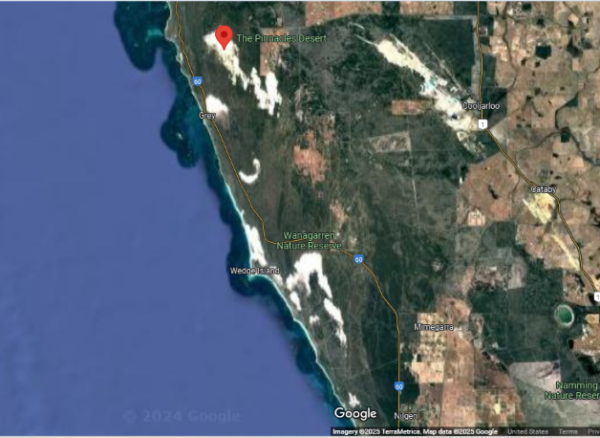

Geologically speaking, the Pinnacles aren’t just infants, they’re neonates with current estimates of their age spanning from 80,000 to 25,000 years BP. There’s general agreement that the limestone that provides the raw material for the pinnacles came from sea shells. Although it’s a desert, it’s quite close to the ocean as you can see from this photograph.

And, of course, with the changing sea level as glaciers formed and retreated, there’s a possibility that the desert was once even closer to the shore. The shells were broken down through weathering and erosion and then blown inland forming high mobile dunes. (The dunes we used for sandboarding are less than 80 kilometers away.) What happened next is a matter of debate.

One hypothesis says they are dissolved remnants of the Tamala Limestone. This means they would have undergone a period of extensive solutional weathering or karstification. (Solutional weathering is a process in which minerals such as calcite in limestone are dissolved by carbonic acid.) Initially forming small solutional depressions, mainly solution pipes, their progressive enlargement over time created the pinnacle topography. (Solution pipes are small vertical pipes that form in porous carbonate rocks.) Under this hypothesis, some of the pinnacles are also cemented void infills (or re-deposited sand). While these are more resistant to erosion, dissolution still would have played the final role in pinnacle development.

A second theory states that they were formed through the preservation of tree casts buried in coastal rocks formed by the lithification of wind deposited sediment called aeolianites. In this scenario, the tree roots became groundwater conduits, resulting in the precipitation and accretion of hardened calcrete. Subsequent wind erosion of the aeolianite would then expose the pillars.

There’s at least a third hypothesis but it’s rather complex and considered to be unlikely so I won’t discuss it.

What I will discuss is the curiosity that, as this aerial view from Google Maps shows,

there are a number of desert like areas in the vicinity but none of the others have these pinnacles. I’m sure that the geologists have posited at least one reasonable explanation but, with a few caveats, I’m going to turn to the explanations of the local people who have been the custodians of this land for tens of thousands of years.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

(Mystic voices conjure up our dreams.)

First, the Pinnacles are constantly changing. Over time, windblown sands may have completely buried them for long periods. Even today, it’s possible that some of the smaller formations such as those seen here,

could be buried by blowing sand only to reappear days later when the wind changes direction. Yes, the Pinnacles you see could be different from the ones I saw. They might have looked quite different merely a few centuries ago. The earliest written mention of the Pinnacles can be found in Dutch documents from the 1650s. They thought the formations were the remnants of a lost city.

With regard to the stories told by the Juat People or other local clans if, in fact, the formations have been periodically covered completely, it would limit the ability of people to develop a consistent narrative about them in much the same way this variability likely contributes to the geological uncertainty regarding their age and formation. Their impermanence or even their recency underlie the lack of consistent stories or Dreaming about the Pinnacles.

One commonality between the tales is that the larger area, if not the Pinnacles themselves was important for Indigenous women, who used it for camping, childbirth, foraging, and Ceremony. The latter, in particular would have pegged it as off-limits to men.

The Punishment – Weapons

In one legend, a group of young men disobeyed tribal laws by walking along a desert path to a sacred place reserved for women. Disobeying tribal laws always resulted in some form of punishment and in this instance, punishment was meted out by the spirits who buried them alive in the sand. As death approached, the young men asked for forgiveness and thrust their weapons through the sand and when we see formations such as these

we are looking at those weapons.

Sunken fingers

A similar tale tells of young men who entered the forbidden women’s area. However, rather than receiving punishment from the gods, they simply sank into the sand. What we see are their fingers breaking through the sand as they struggled to survive.

A final tale simply relates the notion that the stones are ghosts – making the area one to be avoided. I could well imagine this when I saw this formation

that these two figures were engaged in conversation.

Sometimes places surprise you. In visiting the Pinnacles, I both knew and didn’t know what to expect. I found the situation akin to visiting Crater Lake in Oregon many years ago and before there was an internet on which I could blog. I was driving south from Seattle on my way to San Francisco and I thought Crater Lake would be a pleasant diversion of two to three hours – meaning an hour to reach the Park, half an hour to an hour driving the rim, and an hour back to I-5. I knew I’d see a lake in a volcanic caldera but when I reached it on that clear summer day, I became infatuated with the color of the water and its variability as it changed with every viewpoint. I spent far longer than the time I’d allotted to drive around it.

Similarly, I’d seen pictures of the Pinnacles and I expected they’d be interesting but knew they wouldn’t be as imposing as the formations in a place like Bryce or Monument Valley. When the bus dropped us off at the Visitor’s Center and I walked up the road, I found myself enchanted by formation after formation and, seeing more in the distance, a little sad knowing that I wouldn’t have time to walk to see them. I took more pictures than I anticipated I would.

Maybe it’s good you didn’t walk among the Pinnacles or you could have faced some sort of punishment or even disappeared!! That wouldn’t be good…

Really. I’d have probably been one of those small ones that gets buried periodically!