As our flight takes us to Cairns, the last stop on the Great Australian Train Trek, I thought it might be interesting to look at how Uluru became Ayers Rock before having its traditional name returned – at least for the general public. (Enter Ayers Rock into Bing or Google Maps and it will change the search term to Uluru.)

We’ve seen that the first humans reached Australia at least 60,000 years ago and there’s strong evidence that the Anangu People became the traditional caretakers of the land at least 30,000 years ago and that they managed the land and environment largely undisturbed until the first Europeans arrived in the late nineteenth century. We also know the importance of both Uluru and Kata Tjuta in Anangu Tjukurpa so I won’t revisit those elements in this post. Instead, I’ll begin with

the first Europeans.

The earliest European expeditions to this part of South Australia were led by a pair of Williams – William Giles (better known as Ernest) and William Gosse. They were in the area at about the same time in 1873 and each played a role in applying European names to the three large rock formations. Gosse

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

replaced the names Artilla and Uluru with Mount Conner (after M. L. Conner, a South Australian politician who had financed his expedition) and Ayers Rock – honoring Sir Henry Ayers the eighth Premier of South Australia. (Recall that the state of South Australia encompassed the entire area from Adelaide to Darwin until the Northern Territory partially separated in 1907 before transferring its governance to the federal government in 1910.).

Giles

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

attached the name Mount Olga (for Queen Olga of Wurttemberg) to Kata Tjuta.

It would be another 20 years before the next major European exploration of Central Australia and this one came with the intent of analyzing the area’s prospects for farming, mining and tourism.

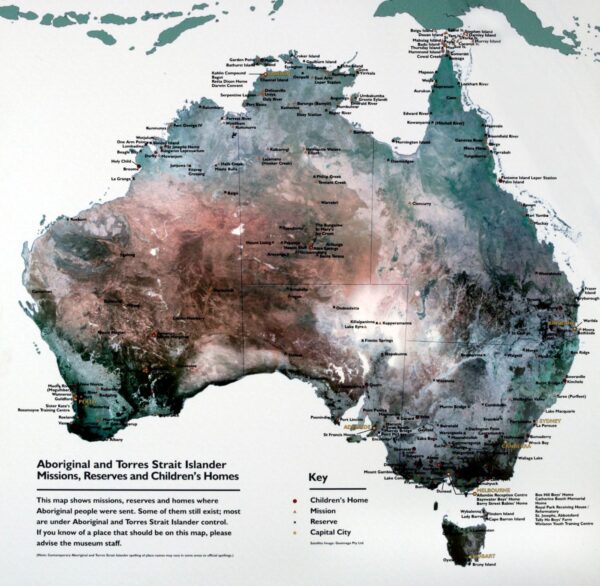

In the 19th century the Australian government began establishing “reserves” for the First Nations People. Although established and managed differently from the Reservations for Native Americans, they were like their U S counterparts in their intent to segreate their residents from white society, controlling their lives and movements, and suppressing their culture.

[Creator Dragi Markovic Copyright: National Museum of Australia]

In 1920, the land that included Uluru and Kata Tjuta was added to the South West Reserve.

Over the next few decades the government reduced the size of the reserves to open land for mining and tourism creating Ayers Rock National Park in 1950. Then in 1958, Kata Tjuta was excised from the reserve and made a part of Ayers Rock – Mount Olga National Park. This further limited Indigenous access though some Anangu continued to pass through their traditional lands to hunt, visit family, and participate in Ceremony. In its continuing effort to discourage Anangu from being in the area, it established a settlement at Kaltukatjara nearly 250km west of Uluru.

1966 – A turning point year

(From little things big things grow)

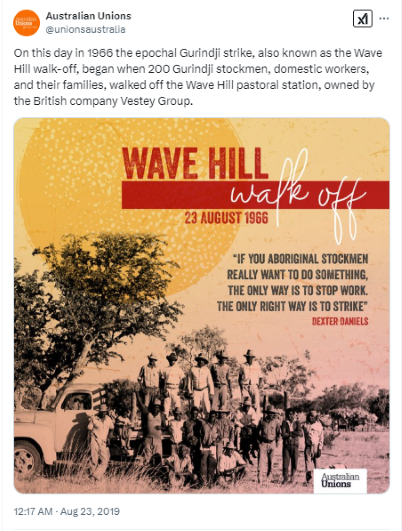

Led by Vincent Lingiari, about 200 Gurindji stockmen, domestic workers and their families began a strike at Wave Hill station in the Northern Territory on 23 August 1966. The dispute needed nine years to fully settle.

Like all of Australia’s First People the Gurindji had lived on their homelands for tens of thousands of years. In 1883 the colonial government granted almost 3,000km² of Gurindji Country to Nathaniel Buchanan. Within a decade, the herd was 23,000 strong straining both an unsuitable environment for cattle and the system of land management the Gurindji had developed over the millennia.

(This pattern was repeated across Australia as pastoralists took possession of First Nations lands and stocked them with cattle and sheep both of which are, invasive species.)

Having come to recognize that remaining in Country was an existential need for all First People, cattle and sheep station owners had a relatively compliant and easily exploitable labor force. So strong is the connection to Country for the Gurindji and all Aboriginal people that they were willing to withstand this exploitation for decades including at places like Wave Hill.

[From Australians Together]

Despite legislation requiring First Nations peoples in the Northern Territory to receive food, clothes, tea, and tobacco in exchange for their labor a 1946 report showed that First Nations children under 12 were working illegally, that accommodations and rations were inadequate, that there was sexual abuse of First Nations women, and prostitution for rations and clothing was taking place. No sanitation or rubbish removal facilities were provided and there was no safe drinking water.

In 1953 all First Nations peoples in the Northern Territory were made wards of the state and in 1959 the Wards Employment Regulations established a minimum scale of wages and rations and conditions applicable to wards of the state who were employed in various industries. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the minimum ward rates for Indigenous People were as much as 50 per cent lower than those for Europeans employed in similar occupations.

In 1965, the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights pressured the North Australian Workers Union (NAWU), to have the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission delete references in the Northern Territory’s pastoral award that discriminated against First Nations workers. However, the well-funded pastoralists, that included the international meat-packing company Vestey Brothers, prevailed upon the commission to defer implementation of the new rule by three years.

On 23 August 1966, Vincent Lingiari led the Wave Hill walk off.

Where the NAWU saw the strike as exclusively about wages and working conditions, for the Gurindji the focus was reclaiming their Country. They demonstrated this as negotiations were dragging on by moving their camp in April 1967 to Daguragu some 20 km closer to their sacred sites. They petitioned the Governor-General grant them a lease of 1300Km² to operate as a mining and cattle lease saying, among other things, We feel that morally the land is ours and should be returned to us. Not surprisingly, he denied their request.

No party remains in power in perpetuity

After losing a national election in 1949, it took 23 years for the Labor Party to return to power but in 1972, the newly elected Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam announced in his election policy speech that his government would ‘establish once and for all Aborigines’ rights to land’.

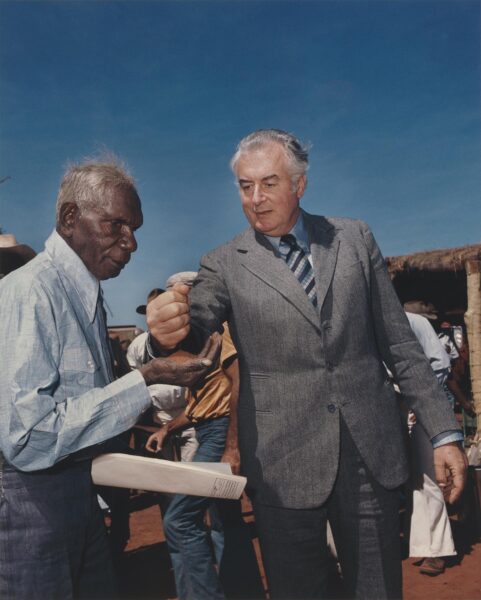

In August 1975 Prime Minister Whitlam came to Daguragu and ceremonially returned a small portion of Gurindji land to the traditional owners by pouring a handful of soil into Vincent Lingiari’s hand with the words, ‘Vincent Lingiari, I solemnly hand to you these deeds as proof, in Australian law, that these lands belong to the Gurindji people’.

[Museum of Australian Photography, City of Monash Collection MAPh 2003.12 courtesy the artist and Josef Lebovic Gallery Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, National Indigenous Australians Agency]

The Gurindji strike was instrumental in heightening the understanding of First Nations land ownership in Australia and was a catalyst for the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (ALRNT), the first legislation allowing for a claim of title if the First Nations claimants could provide evidence for their traditional relationship to the land. It established processes for Indigenous people to reclaim unused Crown land and manage resources.

Inspired by the actions of Vincent Lingiari and the strike at Wave Hill, Uluru’s Traditional Owners began lobbying the government for the right to their country. Their major concerns centered around mining, pastoralism, tourism, and the desecration of sacred sites.

The Central Land Council lodged a successful land rights claim on behalf of Traditional Owners in 1979, but the national park, because it was considered alienated Crown land, was omitted from the claim.

Eventually, the government amended the Land Rights Act to allow the inclusion of national parks in First Peoples land claims and the Anangu were able to reclaim ownership of the national park. On 26 October 1985, the Governor-General of Australia returned the title deeds to the park to Anangu in a handback ceremony on the oval in Mutitjulu community. It was celebrated 30 years later.

Of course there were strings attached. In return for regaining their traditional land, Anangu had to lease the land to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service (now Parks Australia) for 99 years. The board of management was set up in December 1985 with a majority of Anangu members, and the park continues to be jointly managed by Anangu and Parks Australia.

In 1993, the park was renamed and is now Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park. It would be another 26 years until 26 October 2019 before tourists were legally barred from climbing Uluru.