Intermezzo II – Conquistador! The man who would be king

Afonso O Conquistador.

By now, when I write the name Afonso Henriques you should recognize him as Portugal’s first king and because of him Portugal can assert a legitimate claim as the oldest sovereign nation in Europe. For this little diversion, I’ll take you through a slightly more detailed look at the basis for these statements.

In 1109 when Afonso was born – most likely in the city of Guimarães – his father, Henry of Burgundy, and his mother Teresa of León (who was the illegitimate daughter of Alfonso VI of León) were the count and countess of the County of Portugal. Henry had received the territory in 1096 after his promise to recognize his cousin Raymond as king of León, Galicia, and Castile on the death of Alfonso VI. However, Raymond died in 1107 and his widow, Urraca (the only legitimate surviving heir to Alfonso VI), became Queen of Castille when Alfonso VI died in 1109.

Raymond’s death ignited some of Henry’s ambitions and he and Teresa were at odds with Urraca until Henry’s death in 1112. Since Afonso Henriques was only three when his father died, Teresa governed the county. With the County of Portugal as the prize,

[Map from Wikimedia Commons By-Basilio-Own-work-CC-BY-SA-3.0.]

Teresa found herself under pressure to remarry from both the local Portuguese infanções (nobility) and the Galician nobility. It’s unclear whether she secretly married the Galician Fernando Peres de Trava with whom she had an affair but it is clear that her relationship with him prompted most of the Portuguese noble families – who had no allegiance to Galicia – to withdraw from her court.

Afonso, who had been raised by a Portuguese noble family in the northwestern town of Riba de Ave, was more sympathetic to their more Portuguese centric claims than to those of his mother and the Galician. This matter was further complicated by a power struggle between two Catholic archbishops – one in Braga supported by Afonso and one in Santiago de Compastela supported by Teresa.

At the age of 16, Afonso made himself a knight in the Cathedral of Zamora and at age 19, he led a victorious army against his mother with the decisive battle taking place at São Mamede outside Guimarães. He exiled her to a monastery in León where she died two years later.

While he clearly had some ambitions, Afonso was content at this point to have secured the interests of the Portuguese nobility. After Teresa’s death, when his cousin Alfonso VII who had recently quashed a rebellion in Castille, demanded vassalage from the man who would be king, he declared himself Infante dos Portugueses (Prince of the Portuguese) initially settling his court in Guimarães.

[Image of Afonso I -from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

With an eye toward driving the Almoravid Moors from Portugal, Afonso moved his court south to Coimbra where he began to engage them in a series of battles. Although the mists of history have fogged the details, one rather questionable document points to his great victory coming at the Battle of Ourique on 25 July 1139 where he triumphed over Muhammad Az-Zubayr Ibn Umar the Almoravid governor of Córdoba. According to some other questionable historical documents, Afonso then convened at Lamego the first Cortes Gerais (Assembly of the Estates-General) of Portugal where he was given the crown by the Archbishop of Braga, thereby declaring him king and confirming Portuguese independence from the Kingdom of León.

You can make yourself a knight but can you make yourself a king?

Afonso knew that it wasn’t enough to simply have his troops or even the archbishop of Braga (if such was the case) declare him a king to have it come to pass. His nascent kingdom needed both diplomatic and papal recognition. Further, he would need to come to some sort of agreement with his cousin Alfonso VII of León that would avoid persistent combat.

His first step was to find an ally through marriage so he married Mafalda of Savoy the daughter of Count Amadeus III.

[Image of Mafalda of Savoy from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

With an eye toward courting Rome, he built castles, monasteries, and convents as he pushed the Moors into ever shrinking territory simultaneously engaging his armies in skirmishes with those of Alfonso VII who regarded him as a rebel. Through Mafalda he sent emissaries to Rome to negotiate with the Pope and he had them report that he would renounce the suzerainty of León and pledge to become a suzerain of the Pope. Afonso also promised to continue prosecuting his war against the Almoravids until they were driven from the country.

On 5 October 1143 in the Cathedral at Zamora, Alfonso VII of León recognized the Kingdom of Portugal in the presence of the new king and Cardinal Guido de Vico – the papal representative. Afonso Henriques, now Afonso the First, also witnessed the treaty’s signing. He had his kingdom at last.

But he had promises to keep.

As noted above, Afonso had promised the pope that he would continue the Reconquista until he had driven the Moors from Portugal but he didn’t win every battle. In 1142 he had attempted to capture Lisbon and had convinced a group of Anglo-Norman Crusaders to assist him in a siege of the city. But Afonso wasn’t as well prepared as those within the city and his forces eventually retreated while the frustrated and disgruntled Crusaders continued their journey to what they called the Holy Land.

Then, in the spring of 1147, Pope Eugene III authorized a crusade in the Iberian Peninsula, where “the war against the Moors had been going on for hundreds of years.” For Afonso the timing was propitious.

On 15 March 1147, he led 250 of his best knights in an attack on the Moorish city of Santarém. Control of the city accomplished two strategic goals. It ended Moorish attacks on Leiria and it positioned him for a second attack on Lisbon.

On 19 May of that year a large contingent of relatively leaderless “Frankish” Crusaders set sail from Dartmouth, England arriving in Porto on 16 June where the bishop convinced them to meet with Afonso. Having learned from his previous failure, and perhaps finding the papal decree useful, Afonso convinced them to join him in the siege of Lisbon promising them pillage of the city’s goods and the ransom money for expected prisoners. And so it began.

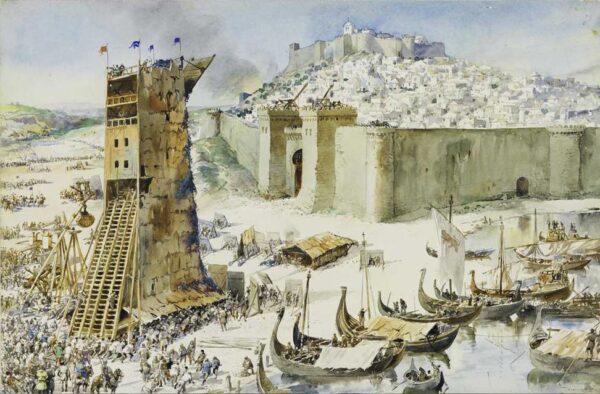

[Siege of Lisbon by Roque Gameiro from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

The siege began on 1 July and lasted nearly four months before ending with the Moorish surrender on 21 October – romantically portrayed in this 1840 painting by Joaquim Rodrigues Braga.

[Moorish Surrender from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Needless to say, the Crusaders engaged in significant plundering.

Although he lived until his mid seventies, reconquered more Muslim territory than any of the other Christian kings on the Iberian Peninsula, and achieved full and final recognition on 23 May 1179 when Pope Alexander III issued the papal bull Manifestis Probatum recognizing Afonso as a vassal to the pope and a king, Afonso died in 1185 and didn’t live to see the Moors completely driven from Portugal. That deed was left to his great-grandson Afonso III who completed the reconquest in 1249 and became the first to declare himself King of Portugal and the Algarve.

So, you see, Portugal became a nation in 1143 and although the Alentejo and Algarve were under Moorish rule as this map depicting the various 1210 kingdoms shows,

they were never a part of any of the many kingdoms that came to comprise the country of Spain. A mere 48 years after Afonso III had retaken the Algarve, King Denis of Portugal met King Ferdinand IV of Castille and León in the small town of Alcañices where, on 12 September 1297 they signed a treaty that established the formal border between the two kingdoms and that border has remained little changed for more than seven centuries.

In the next post, we’ll explore another of Lisbon’s charming neighborhoods, Chiado.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026