7 June.

I’ll start today with a bit of recognition for the hotel. After my rant yesterday – most of which still holds true – I will acknowledge that the free breakfast, while not sumptuous, is a nice amenity. The breakfast is served in the Michele’s small coffee shop accessible from the lobby. Interestingly, the choices included fare that seemed designed to cater to westerners and Koreans. The folding table “spread” included kimchi and some sort of salty soup as well as more traditional western fare of eggs, cereal, toast, and the like. We’d been told that breakfast would be available from 07:00 – 09:00 and that the guided tour scheduled for the morning would depart a bit after nine. In the first example of the stochastically resonant temporal rhythm that manifested itself during the trip, everyone drifted in between 07:00 and 07:30.

The tour was scheduled for a half day and our guide Odka, who’d been on the ride from the train station, met us promptly at 09:00. Before boarding the bus, Odka warned us to beware of pickpockets. G had issued a similar warning yesterday and we would hear that alert repeated so often during our stay in UB that one might think the problem was endemic. (By the way, according to Odka, even Mongolians frequently use UB in talking about their capital city so there’s nothing untoward about my use of it.) Our first stop would be the Gandan Monastery

which is one of the few left standing from the purges initiated by Choibalsan (whom you should remember from yesterday’s entry) that destroyed most of the monasteries and killed over 15,000 lamas.

Odka told us that pigeons are considered sacred by Buddhists thus we should be prepared for flocks of “friendly” pigeons in the monastery. They may be sacred but these pigeons have nothing on their relatives who congregate in Trafalgar Square and who are more numerous and more assertive. Construction of the monastery began in the first third of the nineteenth century and was ordered by the fifth Jebtsundamba who is the spiritual head of the Gelug or Yellow Hat lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia. This individual is the highest-ranking lama in Mongolian Buddhism.

Odka failed to explain the difference between Yellow Hat lineage and Red Hat lineage so I will. It deals mostly with the manner in which Buddhist traditions are interpreted and studied. According to the website Himalayan Art Resources:.

Red Hat & Yellow Hat is a late classification that is most commonly used in Mongolia and China and rarely in Tibet or the Tibetan cultural regions of the Himalayas. Yellow Hat refers specifically to the Gelug School dominant in the two areas of Mongolia and China after the 17th century. Red Hat refers collectively to all of the Buddhist Schools that are not Gelug, such as Nyingma, Sakya and Kagyu, etc. Tibetan followers of the Gelug Tradition referred to themselves as the Yellow Hat Tradition, this is found in Tibetan Gelug writings and liturgical verses, but it is unclear when this classification began and when the other non-Gelug traditions became the Red Hat Tradition. According to this system the most important and iconic of the ‘Red Hat’ Lamas is Padmasambhava. The principal ‘Yellow Hat’ lama is Je Tsongkapa, founder of the Gelug Tradition.

Over time, the Gandan Monastery became the center for Buddhist learning in Mongolia with temples for daily service, veneration of Avalokiteshvara, and colleges of Buddhist philosophy, medicine, astrology and tantric ritual. Avalokiteshvara is the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion.

Adding to its historical significance, the thirteenth Dalai Lama – the head of the Guleg branch of Tibetan Buddhism – (Tenzin Gyatso the present Dalai Lama is the fourteenth) resided for some time in this monastery in these quarters:

It’s possible that he issued his decree for Tibetan independence during his time in Gandan but I’m uncertain. Odka’s information was coming at us in rapid fire fashion.

We proceeded around the corner to a temple where the monks were chanting. They chant twice a day – a long session of two to three hours in the morning and a shorter session after lunch. Observers are permitted. Some assume positions of prayer while others, like me, simply watch. The scent of incense, prevalent throughout the monastery, was stronger in the ornate temple. Most of the chanting was accompanied by rhythmic drums, cymbals, and bells. Flanking the chanting monks were two pair of enormous horns – perhaps six meters long from mouthpiece to bell – resting on carved wooden bases. Monks would blow into these horns which issued a foghorn like sound to signal the end of each chanting section.

In a theme that recurred throughout the day, Odka pointed to a building housing the 26-and-a-half-meter-high Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva that blends three distinct architectural styles: Mongolian, Chinese, and Tibetan.  In this instance, the layering of styles reflected influences from the various schools of Buddhism rather than resulting from the military and political forces that have often tormented this nation. There’s a plan to build a larger statue of the Bodhisattva and the feet of the statue and plans for it are displayed in the monastery.

In this instance, the layering of styles reflected influences from the various schools of Buddhism rather than resulting from the military and political forces that have often tormented this nation. There’s a plan to build a larger statue of the Bodhisattva and the feet of the statue and plans for it are displayed in the monastery.

Our next stop was the Summer and Winter Palaces of the Bogd Khan. On the way, I asked Odka about the scores of karaoke venues I’d seen and she confirmed that, yes, karaoke is quite a popular pastime in UB because there simply aren’t a lot of alternative entertainment options. The Bogd Khan’s “palaces” are adjacent to one another and, although interesting, they have gone to seed a bit as you’ll see from the pictures. Time for a two-part rant:

I took only a few surreptitious photos here. Throughout the trip I’d find that permission to take photos inside many of the sites we’d visit frequently entailed an additional charge. I opted not to pay the fee here because it was simply exorbitant – the equivalent of nearly twenty-five U S dollars. There was only one person patrolling the grounds, so I broke the rules from time to time. I’m not sure of the reasoning behind this policy but I think most tourists would find it somewhat disconcerting.

Part two of the rant concerns the rather dilapidated condition of the grounds and structures. Those of you who read the journal from my trip to Malta may recall that I railed against the Maltese for not having a good sense of how to promote their attractions, how to make them easy to locate, how to include appropriate merchandizing opportunities, and so on. Promotion isn’t a particular problem in Mongolia but ease of access (as you’ll learn in a subsequent entry) and maintenance certainly is. Perhaps they don’t yet have the funds to restore these places to something that approaches their original state, but they certainly could mow the grass and clear the weeds.

A brief history lesson: The Bogd Khan ascended to the throne as Emperor of Mongolia in 1911 when what the Chinese call Outer Mongolia declared independence from the failing Qing dynasty. He had, early in his life been recognized as the eighth reincarnation of the Bogd Gegen and, was thus not only the spiritual leader of Mongolian Buddhism and the third most important person in the Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy, but he also became the political leader of the country. He lost power when Chinese troops occupied Mongolia in 1919 but was restored to limited power after the 1921 revolution led by Damdin Sükhbaatar. He remained on the throne until his death in 1924.

Among his quirks was an obsession with collecting exotic stuffed animals. Many of these are on display in the Winter Palace. The Winter Palace, built in a European Style, has its own bit of intrigue. The construction was a gift to the Bogd Khan from Czar Nicholas II. Ever buffeted between the Chinese and the Russians, the building raised the ire of the Chinese royal court. The Chinese were still a threat and held some sway over Mongolia and they accused the Bogd Khan of showing favoritism toward the Russians. His solution was to put a distinctly Chinese roof on the structure. This placated the Chinese while graciously accepting the gift from the Russians.

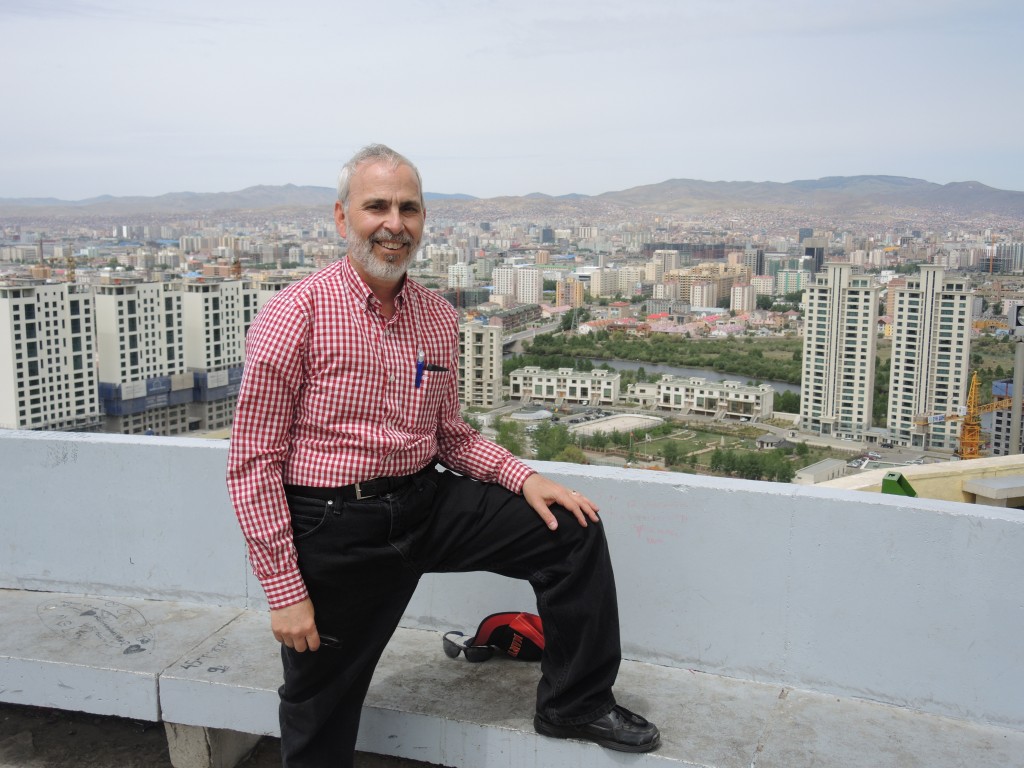

The last official stop on our guided tour was the Zaisan Memorial. It sits on a hill south of the city and was built to honor the Soviet soldiers who defended Mongolia during World War II.

The monument pictured above is incorporated in the circular memorial that depicts scenes of friendship and support from the Soviet Union for the people of Mongolia. From the upper parking lot, you have to climb 300 steps to reach the top. The climb, however, is worth the walk because of the thrilling panoramas of UB.

For more panoramas, and pictures of the memorial without me, follow this link.

In one photo you’ll see the hill with the inscription that was visible from the monastery. In another I look down at the Buddha Garden featuring a 23-meter- high Buddha. Come back tomorrow for tales of the afternoon and evening in Ulaanbaatar.