Looking over Lisboa.

Two of the distinguishing traits of Lisboa (henceforward) Lisbon are its hills and its neighborhoods. In fact, while the sobriquet the City of Seven Hills is certainly better known when applied to its Italian counterpart, it’s also been used to describe Lisbon.

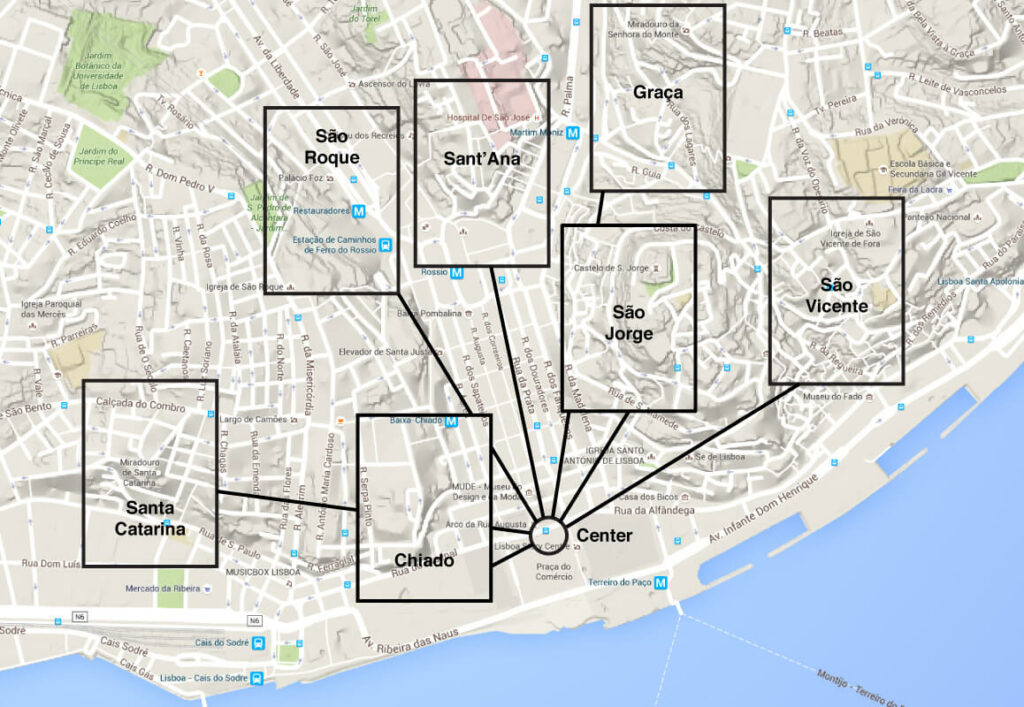

The most common explanation for this is that the Romans, who called the city Olissipo, saw a topographic resemblance to their home city. In the 17th century, Frey Nicolao d’Oliveira provided a written description of what he called the seven mounts: São Vincente, Santo André (also called Graça), São Jorge, Sant’Ana (also called Hill of Saúde), São Roque, Chagas (or Chiado), and Santa Catarina. Although I won’t discuss them all, and you can read a brief description of them here, it’s said that each played its own unique role in the city’s founding and growth.

[Map from leoxavier.net/seven-hills.]

(According to the website The Culture Trip, however, Lisbon is a city of eight hills not seven. They write, “The idea of a city on seven hills, like Rome, is certainly a romantic one and perhaps that’s one reason why this description of Lisbon stuck. The original reference came from a book called O Livro das Grandezas de Lisboa where the author listed seven beautiful hills but forgot the highest of them all – the hill of Graça where the Miradouro Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen offers one of the most dramatic sweeping views over the city, facing the river, castle and bridge.”)

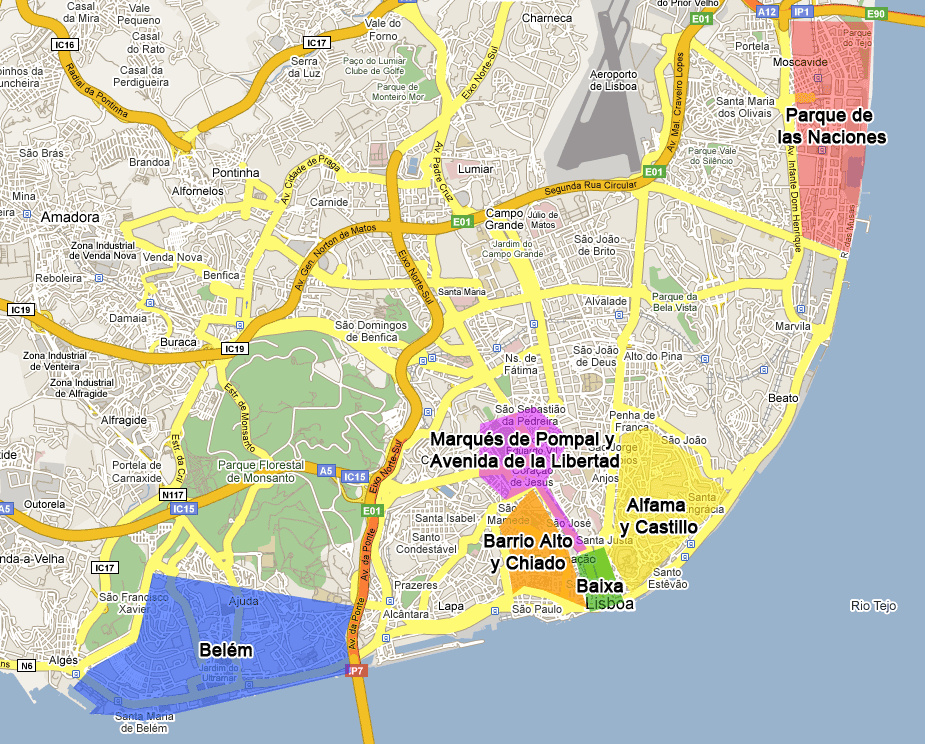

Of greater importance to me was getting a sense of the neighborhoods occupying those hills and, to that end, I had Portugal Trails arrange for a guided half day walking tour. My guide, Ana arrived a few minutes late because PT had changed my hotel the previous day and while they’d notified me, they had failed to let her know. Fortunately, they’d only moved me 500 meters or so north of the original booking so she didn’t need much time to arrive once she discovered the error. Ana guided me through two of the main neighborhoods that most visitors see and that were in close proximity to the hotel – Bairro Alto and Chiado. She also provided a brief overview of a pair of other close by neighborhoods – Baixa and Alfama – that I’d pass through. I’d venture into several more on my own – including two later in this afternoon – before departing Lisbon Friday.

[Map from lisbon.net.]

Let’s get started.

We left the hotel and started south along the Avenida (the thin pink strip above). One of our first stops was at the Avenida Metro station where, with Ana’s guidance, I purchased a 24 hour pass for Lisbon’s transit system. (The pass activates at the time of first use not at the time of purchase.) Our first above ground stop was at the World War I memorial.

To understand the importance of this particular monument we need to dip our toes in the stream of history. At some later point in this blog I’ll provide a more in depth look at Portugal’s history and foundation but for now, let’s say that, with the 1139 victory by Afonso Henriques in the Battle of Ourique, its first recognition in the Treaty of Zamora in 1143, and the Manifestis Probatum issued by Pope Alexander III in 1179, it wouldn’t be an extraordinary claim to assert that Portugal is the oldest sovereign nation on the European continent.

While Crusaders from England played an important role in helping establish Lisbon as Portugal’s capital in the 12th century, an event of equal importance took place nearly 200 years after the papal recognition. On 16 June 1373 Edward III of England and Ferdinand and Eleanor of Portugal signed the first Anglo-Portuguese Treaty establishing “perpetual friendships, unions, and alliances” between the two nations. In 1386, the Aliança Luso-Inglesa or Anglo-Portuguese Alliance so strongly reinforced the 1373 treaty that it is today the oldest known international alliance in recorded history that is still politically in force.

At the outset of the First World War, Portugal sought to remain neutral – as it would do with greater success in World War Two – but when Germans began attacking outposts in what was then Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique) the United Kingdom invoked the treaty and Portuguese soldiers fought beside Allied forces on the Western Front. The monument commemorates the lives of the 55,000 Portuguese troops who fought in and the more than one in five who died in that “war to end all wars.”

When alto isn’t alto.

When Ana told me our first stop would be Bairro Alto, my brain flashed back to my last trip out of the U S and the flights from Asuncion to Santa Cruz to El Alto, the suburb of La Paz, Bolivia that’s home to that city’s airport. El Alto sits at an altitude of 4,150 meters and left me gasping for breath after walking just a few steps. Fortunately, we wouldn’t need an airplane to get to Bairro Alto but instead I’d activate my metro ticket and we would ascend a mere 72 meters using the Elevador da Glória followed by a few steps up to the Jardim de São Pedro de Alcântra at what is considered the northern limit to the neighborhood. There we were treated to this view of Lisbon

among others. The castle in the distance is in Graça on the hill of São Jorge.

We began walking south and Ana provided a little of the neighborhood’s history. Commercial development in the latter part of the 15th and early 16th centuries brought more and more people to Lisbon and the neighborhood began to take on a formal structure with the construction of the city’s first formal planned grid network of roads and the first houses all completed just outside Ferdinand’s city wall in the first two decades of the 16th century. At this time the counts of Andrade and Atouguia owned most of the area and it was called Vila Nova de Andrade. An earthquake in 1531 accelerated the construction of houses for the common folk in Bairro Alto but for centuries the neighborhood principally remained home to the bourgeoisie and aristocracy of Lisbon.

Bairro Alto was among the few areas not significantly impacted by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake but the Marquês da Pombal developed plans to restructure the urban fabric between the Bairro Alto and neighboring Baixa. This included standardizing the wide avenues called largos, the squares, and other roads. Most of this construction occurred between 1760 and 1780. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the nobles began selling their houses and palaces and moving to other parts of the city. This is the time the character of the neighborhood began to change.

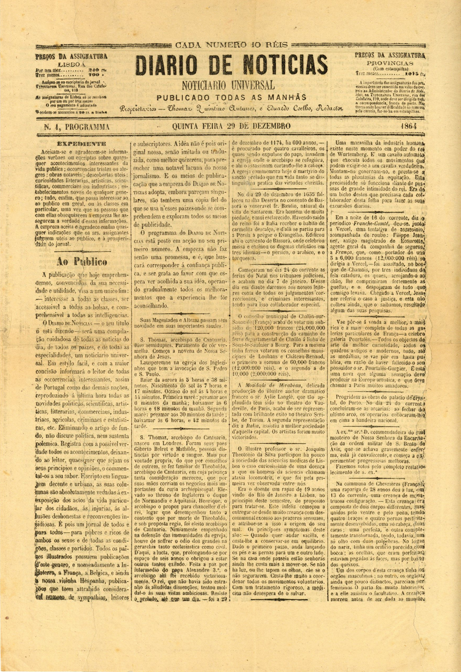

In addition to new residents, a number of nascent newspapers moved into Bairro Alto. However, the Portuguese historically had a fraught relationship with the press and it wasn’t until 1864 with the first appearance of Diáro de Notícias

[Image from News Museum Portugal.]

followed in short order by Diário de Lisboa and O Mundo that journalism and journalists came to be the principal occupants of Bairro Alto. it remained the headquarters of the national press until the 1970s. Today in Bairro Alto, only the sports newspaper A Bola remains.

Naturally, even in the 19th century, where you had journalists, seedy, smoke-filled bars and cafés serving cheap food were soon to follow. And where you had seedy bars, cheap cafés, journalists, and lots of late night shenanigans, prostitutes inevitably found their way up from the port and began plying their trade in many local brothels. Young artists and other writers also found their way to Bairro Alto and neighboring Chiado. Although fado had been sung in Lisbon for decades, it was here that many singers of fado created a distinctive musical approach quite different from the one to be developed by students in the famous university town of Coimbra. Whether one’s preference is for Lisbon fado or Coimbra fado, there’s no dispute that fado has become Portugal’s signature musical style.

Thus, even today, Bairro Alto retains an almost bipolar nature. During the day, it can be quiet enough along certain streets that taking a photo like this one

is relatively easy. At night, the streets of Bairro Alto can look like this

[From sara-sees.]

with parties and music floating into the night air from one fado bar after another until the wee small hours of the morning.

After a brief historical intermezzo, Ana and I will see you in Chiado.