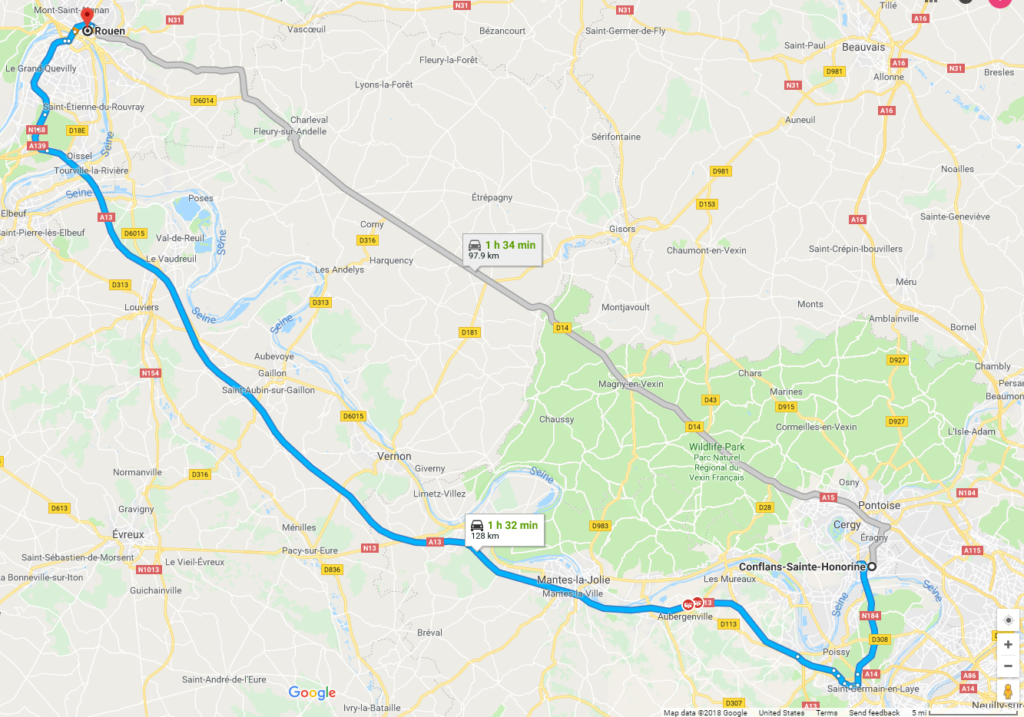

I don’t recall whether we’d set sail during dinner but certainly by the time of Tim and Jie’s concert we were well underway for the longest passage on the outbound segment of our river cruise. When we awoke in the morning, we had traveled more than 125 kilometers

and were docked in the day’s port of call, Rouen. (If you use the map in this instance, don’t follow the blue road route but rather the snaky course of the Seine.)

(It’s hard to approximate the French pronunciation of Rouen. It’s quite far from English efforts that generally sound like “roo-ON” or sometime “roo-AW”. For many French people this city’s name is monosyllabic and begins with a uvular trill – a sound most English speakers find difficult – followed by the open mid back nasal vowel sound {sort of akin to “aw”} and ending with a trace of the voiced nasal consonant. I think to many English speakers it would sound a bit like ‘Rwawn” with the uvular trill added hence today’s pun.)

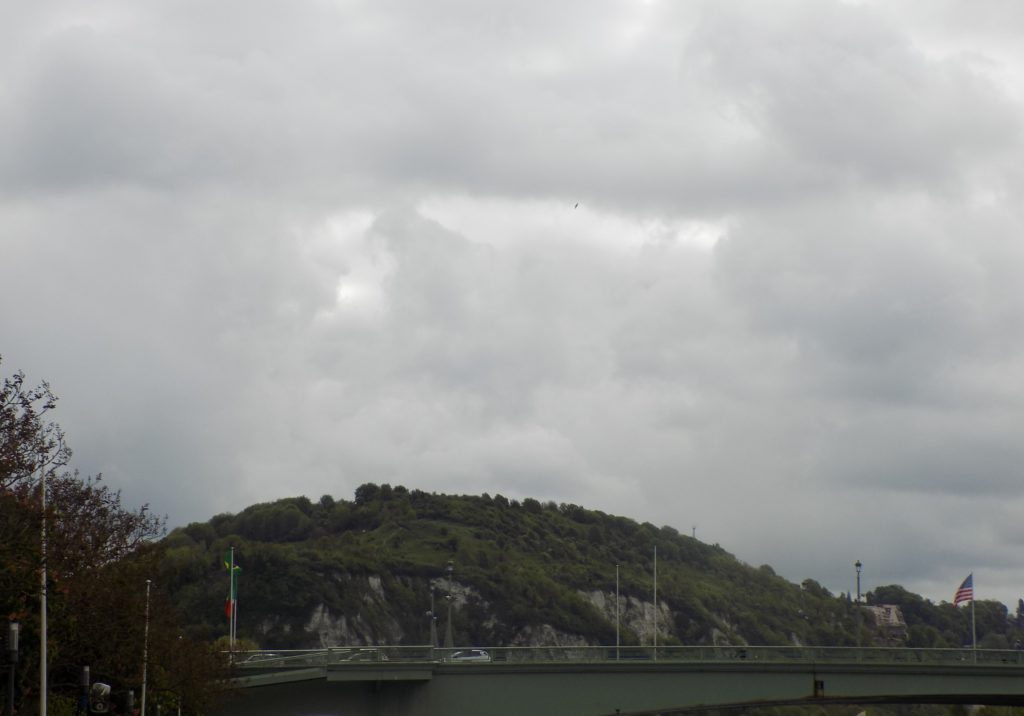

And, as we stepped onto the dock, it looked as though the weather gods remained unwilling to provide us with a sunny day.

Rouen history – more than just Jeanne d’Arc.

For some readers, the execution of Joan of Arc provides the signal image of Rouen’s place in history. It’s more than that, of course, and its history begins with the establishment of a town called Ratumacos by a tribe of Gaulish people known as the Veliocasses. This tribe was among those who formed a coalition of local groups who tried to resist the Roman invasions led by Julius Caesar in the period between 57 and 52 BCE. So, some semblance of the town has been here for a long time. Once the Romans conquered the area, they called the town Rotomagus.

Toward the end of the third century, two events converged that elevated the town’s prominence. The first was the arrival of Saint Mellonius. He was the second Bishop of Rotomagus and, by some accounts, is said to have been responsible for spreading Christianity in the region. The second was the ascension of Diocletian to emperor. (Diocletian was emperor at the time of the martyrdom of Honorine.)

Diocletian might have been the ancient world’s most preeminent bureaucrat. During his 20-year reign (285-305), he separated the Roman empire’s civil and military services enlarging both and, in the process reorganized the provincial divisions within the empire. Diocletian sub-divided the area known as Gallia Lugdundensis (shown in orange below) into two regions.

[Map from romeacrosseurope]

Rotomagus became the capital of the new division called Gallia Lugdundensis II. (If you enlarge the map and look at the northeast of the orange section, you will see both Lutetia [the cité of mud] and Rotomagus.)

The town retained a measure of importance over the centuries keeping its status even after being overrun by the Vikings in the ninth century. The leader of this particular band of Norseman was Hrólfr or Latinized as Rollo. Then, in 911, Charles III (The Simple) named Rollo the first Duke of Normandy and he established the capital of his duchy at Rouen where it remained until William the Conqueror moved it to Caen in the last half of the 11th-century.

Using its location on the Seine, the city continued to grow and prosper for centuries mainly by importing tin and wool from England and developing a thriving textile industry. It also exported wheat and wine. (Although generally characterized by prosperity, Rouen’s growth was far from linear or placid. The city was subject to insurrections and oppression of varying intensity, massive fires and other catastrophes, and the expulsion by Philip IV in 1306 of the city’s estimated 6,000 Jews {from a total urban population between 35,000 and 40,000} amid other turmoil.)

The population of Rouen had grown to approximately 70,000 when the city surrendered to Henry V of England in 1419 approximately seven years after a daughter was born in Domrémy to Isabelle Romée and Jacques d’Arc. They named her Jeanne.

And now we come to Jeanne.

Beset by visions from the age of 13, Jeanne eventually convinced Charles VI to allow her to travel with a relief expedition to the besieged city of Orléans. Whether by coincidence, a new military strategy, or as some would come to believe, by miracle, the year long siege ended barely a week after her arrival.

[Painting from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

It’s important to note that Jeanne’s participation in battles wasn’t a string of uninterrupted successes. She was present at the failed sieges of Paris and La Charité in September and November 1429 respectively. Although she’d attended the coronation of Charles VI, these setbacks eroded some of the court’s belief in her. Jeanne probably hadn’t made the wisest decision in siding with Charles. Charles VI, who was known as both le Bien-Aimé (the Beloved) and Le Fou (the Mad), under the influence of Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, had signed the Treaty of Troyes granting the succession of the French Throne to Henry V of England thereby disinheriting their own son.

While leading a volunteer army to try to break the Burgundian siege of Compiègne, Jeanne was captured by the Burgundians on 23 May 1430. The Burgundians were engaged in a civil war with the Armangnacs who supported the house of Valois – to which Charles VII belonged. The Burgundians supported the house of Valois-Burgundy who were allied with the English.

Jeanne was initially imprisoned at Château Beaulieu. After a nearly successful escape attempt, her captor, Jean de Luxembourg moved her farther north to Château Beaurevoir where she remained from 10 July until 9 November 1430. Then, John of Lancaster, the brother of Henry V, negotiated (essentially bought) Jeanne’s release from Château Beaurevoir. He subsequently had her brought to Rouen which was effectively the capital city of English power in northern France.

Legal proceedings against Jeanne began on 9 January. After being accused, tried, and convicted of heresy, Jeanne was executed by being burned at the stake a bit less than five months later on 31 May.

(The above photo marks the spot of Jeanne’s execution {Le Bûcher de Jeanne d’Arc} beside the boat shaped Eglise de Sainte Jeanne d’Arc a place we reached at the end of our morning tour. You can see more photos from the morning and of this church here.)

The accusations and trial of Jeanne had been so outrageously biased that, after the end of the Hundred Years War, upon a request by the Inquisitor-General Jean Bréhal and Joan’s mother, Pope Callixtus III authorized a “nullification trial.”

The purpose of the trial was to investigate whether the trial of condemnation and its verdict had been handled justly and according to canon law. Bréhal began his investigation in 1452 and a formal appeal followed in November 1455. His final summary written in June 1456 describes Jeanne as a martyr. The nullification trial reversed the conviction and the appellate court declared her innocent on 7 July 1456. Of course, the decision came about a quarter century too late to do Jeanne any practical good.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

“Would it be too waggish to call it the first “tax shelter”?”…As one with a waggish disposition, my answer is an emphatic no…I would also call it clever and funny.

Once again, your piece is filled with rich detail and nuance that enhanced my enjoyment and knowledge. I particularly enjoyed your description of the architecture and construction methods.

Having married into a Jewish family, I have become well versed in their holidays and traditions and have developed an interest in Jewish history over the years so I appreciate the discourse.

I appreciate your comments. The fact that they’re complimentary is great for my ego but simply seeing comments that aren’t spam gives me some enjoyment.