At the end of the previous post I wrote that although the relationship the Indigenous People of Australia have with Country is “similar to the relationship the Indigenous People of America had with their land, it is unlike it in subtle ways that are difficult for me to express.” Nevertheless, that’s the goal of the coming posts. (I’ve chosen to use North America’s First People mainly because of their cultural and spiritual similarities with Australia’s First People, because many Australians drew this comparison, but also because I think many readers have some degree of familiarity with Native American Culture.)

As I begin, please keep in mind the Acknowledgement of Country I included in the initial post in this series. It holds great relevance with regard to this subject. It was:

The travels reported in this journal will take me through places cared for by many family and language groups who are traditional caretakers and custodians of Country through their continuing connection to land, sea, air, culture and community. I acknowledge the custodianship and care of Country by all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and offer my respect to all Elders past, present, and emerging.

Looking at the ground to turn things up

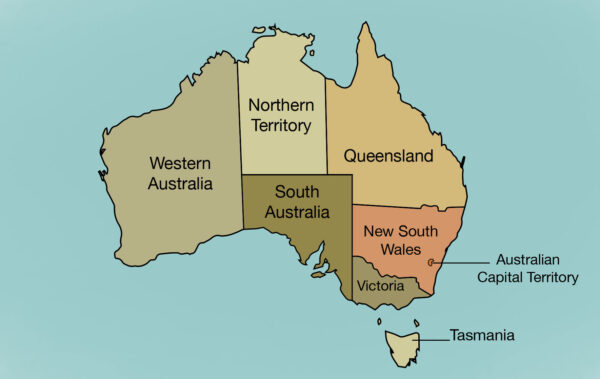

As always, I believe establishing a foundation and providing context are crucial factors in gaining an understanding of new concepts and information so please bear with me as I try to add some historical perspective. In that same first post, I included this Digital Classroom map of Australia.

It’s important now to look at this map produced by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS).

According to their disclaimer the map, “is not intended to be exact” but it does serve, “as a reminder of the richness and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia.” I haven’t counted the number of groups on this map but estimates range from as few as 300 to as many as 500 distinct language groups. There’s uncertainty because we must rely on oral traditions and we don’t know if or when some groups might have consolidated but we certainly know some have been lost to time and conquest.

How long has this been going on?

(Through the mists of time.)

As I’ve been considering what I think I understand about the comparative cultures of Native Americans and First People of Australia and trying to find the language to describe the similarities (but more importantly the differences) my brain needed to discern a reason. I can’t say that there’s any validity to the position I’m about to take and I don’t know if there’s any research to support my supposition so please keep that in mind as you read.

My hypothesis is encapsulated in two words. Time and isolation. Even excluding the notion of time in a cosmological frame, the much shorter Earthbound timescales applied to geology or Darwinian evolution of species are difficult for our brains to fully grasp. (Yes, bacterial evolution can occur rapidly and some short term evolutionary changes can happen in a matter of a few hundred or a few thousand years but long term evolution typically requires timescales of a million years or more.) Given that humans produce a new generation every 25-30 years and under the right conditions can live for only about a century, thinking in terms of even the 13,000 years (or perhaps as long as 30,000 years) for the earliest evidence of humans in the Americas is challenging.

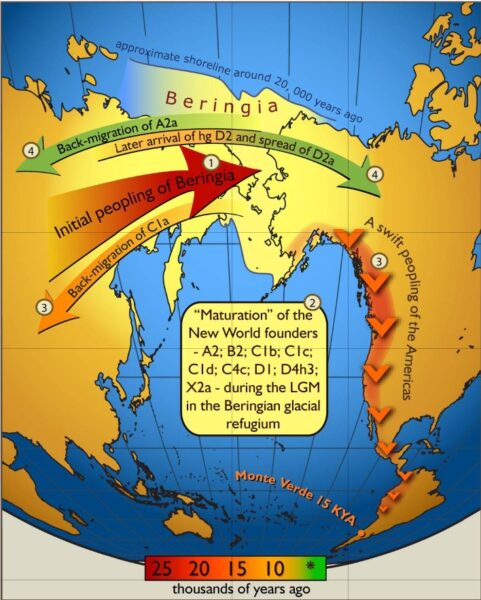

[From Wikipedia – By Erika Tamm et al – Tamm E, Kivisild T, Reidla M, Metspalu M, Smith DG, et al. (2007) Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders. PLoS ONE 2(9): e829. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000829. Available from PubMed Central., CC BY 2.5]

For perspective and ease of arithmetic, I’m going to round some numbers and make some assumptions. Let’s use 25 years per generation and a human arrival time in the Americas of 25,000 years ago. Simple math creates 1,000 generations of descendants from those first people. When the first Europeans arrived it would have been on the order of 920 generations. Many tribes had become more settled but their physical and spiritual relationship with the land was little altered. Next, let’s say that the U S declared its independence 250 years ago. That’s a mere 10 generations. Think of the societal changes that have occurred in those 10 generations. Now consider how the Native American culture might not have changed had there been no interaction with Europeans. Now layer that over the span of the additional 100 generations of isolation for Australia’s First People. Here’s a visual representation.

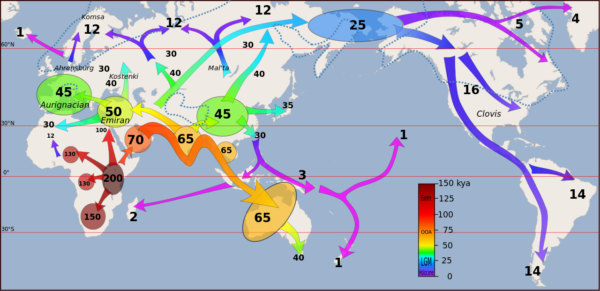

[From Wikipedia By User:Dbachmann – Own work;Map: File:World map blank shorelines.svg (the shoreline map is {{PD-USGov-USGS}}, derived from a mercator svg map posted in 2005, extracted from an original file released by pubs.usgs.gov), CC BY-SA 4.0.]

Evidence, please.

In 1987 Bruce Woodley of the Seekers and Dobe New of the Bushwhackers collaborated to write this song (Pay close attention to the lyrics of the opening verse.):

At the end of the verse, Woodley sings “For 40,000 years I’ve been the First Australian.” In the nearly four decades since he wrote that song, archaeological studies have pushed the arrival date of those first Australians to at least 65,000 years.

Near the border between Arnhem Land and Kakadu National Park about 50 kilometers from the coast is Madjedbebe – a sandstone rock shelter that is currently the oldest known archaeological site in Australia. Part of the traditional lands of the Mirarr, an Aboriginal Australian clan of the Gaagudju People, excavations conducted in close collaboration with the local Indigenous community at Madjedbebe have provided evidence suggesting human occupation possibly as early as 65,000 years ago (± 6,000 years), but by at least 50,000 years ago. The site revealed stone tools used for seed grinding, ochre sticks used for drawing, and evidence of multi-step cooking techniques still used today.

How did they get there? Certainly not on foot.

While I’ve discussed northward human migration out of Africa in other posts throughout this blog, there’s a strong indication that there was also a Southern Dispersal Route with evidence pointing to early humans populating places such as Jwalapuram in India at least 74,000 years ago. This migration would have spread to both Continental and Maritime (or Insular) Southeast Asia (MSA) and it’s likely that the first people to populate Australia originated there.

We’ve seen in previous posts how sea levels rise and fall as Earth’s glaciers advance and retreat. It’s likely that sea levels were lower as the earliest Australians were journeying from MSA to the proto-continent called Sahul. (Until a period between 8,000 and 6,000 years BP, New Guinea, Tasmania, and modern Australia were a single landmass called Sahul.) Presently, 25,000 islands comprise MSA including the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor.

[Map adapted from Objective Lists]

If there are 25,000 islands today, it’s likely that there were even more islands when sea levels were lower. Computer simulations have suggested that sea currents in the late Pleistocene Era might have facilitated travel between these more numerous islands. The most commonly suggested routes would have originated in Indonesia – perhaps near Sulawesi – and reached the northern coast of the Australian continent either through Timor or New Guinea. Alternatively, a more northern route through the Indonesia Moluccan archipelago to New Guinea would have had the advantage of having a target landfall visible on all legs of the journey which would have been helpful to these earliest known seafarers traveling using rafts or, in shallower water, canoes.

Sometimes I can’t help but wonder what might have motivated these early humans to embark on these migrations. Our closest relatives in the family of great apes have made no obvious effort to expand their territory beyond the environments to which they’ve adapted. Migrating animals such as birds and whales shuttle between specific feeding grounds and breeding areas. Human migration, on the other hand, is essentially unidirectional. We leave one place to settle someplace new.

Now, I can imagine that the humans that crossed the Bering Land Bridge did so at least in part because of a scarcity of local resources. Ice age life in northern Eurasia was probably challenging enough that people might have sought someplace better and environmental circumstances might have already prompted some cultural changes.

But what of these people populating Sahul from MSA. Resources there were likely diverse and ample and life relatively comfortable. Why leave? Is there something inherent that makes us want to travel and explore? Perhaps, this is why I travel. Perhaps somewhere inside us we all believe

[By WhiteLily]

Adventure is out there!

Given their propensity for movement, it’s likely that these early explorers and migrants would have begun dispersing across the continent soon after their arrival much like their counterparts would do in the Americas thousands of years later. This dispersal might have accelerated as sea levels rose and coastlines receded. Now that we’ve seen how the continent might have been populated, we can look at some of their beliefs in a coming post. First, we’ll make a brief stop in the ghost town of Cook.

Thanks for the new posted information on the history of Australia. What a wonderful song!

It is a terrific song, indeed. There are some who think it should become the country’s national anthem.

Probably the most comprehensive attempt to analyse the migration and habitation of the continent. Some very thoughtful postulations.