I once had a girl – A visit to Honfleur – part 3

Somewhere there’s music.

As I noted at the end of the previous entry, there’s another son of Honfleur whom the town honors. His name is Erik Satie. Born Éric Alfred Leslie Satie on 17 May 1866 in Honfleur, Satie displayed an interest in, though not an exceptional talent, for music from a young age. He enrolled in the Paris Conservatory at 13 with studies concentrating in piano and solfeggio (the six-tone scale used in Gregorian chants). He lasted three years before being expelled for failing to meet the minimum requirements.

After joining and then contriving his discharge from the military in 1886, he published his first compositions – Trois Mélodies (which included – Les Anges, Élégie and Sylvie – a structure he would use frequently and to which he would specifically return in 1916).

Probably best known for his Gymnopédie No 1,

Satie led an avant-garde charge that reshaped 20th-century music. The great American composer John Cage said of Satie, “It’s not a question of Satie’s relevance. He’s indespensable.”

His life, like his music, was famously eccentric. In fact, describing Satie as eccentric is akin to describing grass as green.

After a failed romantic affair (the only one of his life) with Suzanne Valadon (who led a remarkable life of her own), Satie moved to Montmartre, bought seven identical, grey velvet corduroy suits that he wore without variation for a decade, founded his own one-man religious sect, and allowed only dogs to visit the small room he rented.

And then, of course, there were the titles of many of his compositions –

Préludes pour un chien (Preludes for a dog) followed closely by Préludes flasques (pour un chien) (Flabby Preludes – for a dog) and concluding with Véritables Préludes flasques (pour un chien) (True flabby preludes – for a dog);

Embryons desséchés (“Desiccated embryos”); and

Croquis et agaceries d’un gros bonhomme en bois (Sketches and annoyances of a big man in wood)

to list just a few.

Satie certainly inspired the music of Ravel and Debussy. Although Ravel described Satie’s compositions as “brilliant and clumsy,” Satie and Debussy had a long and deeply abiding friendship. During his lifetime, Satie also collaborated with among others, poet and playwright Jean Cocteau, Picasso, and Sergei Diaghilev founder of the Ballets Russes (about whom you can read in my visit to the Dansmuseet in Stockholm).

His work with the filmmaker René Clair on the 1924 film Entr’Acte, which itself was the entr’acte for the Ballets Suédois’ (Diaghilev’s predecessor company to the Ballets Russes) production of Satie’s Relâche at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, is considered groundbreaking for the manner in which it connects with the film’s imagery. (Recall that Théâtre des Champs-Élysées is the venue where our group saw the Rotterdam Philharmonic and Yuja Wang.)

As would befit someone like Satie, the Maisons Satie a few blocks northwest of Saint Catherine’s church, is more of an anti-museum than a traditional museum and it begins with the entrance where you’re given a headset that doesn’t directly explain the exhibits but that imagines conversations that might have taken place at or about them.

Entry to the exhibit space is controlled by a pair of red and green lights. Given the green light, you enter a space with stacks of newspapers and a cluster of umbrellas hanging on the wall before you walk into a room where you’re confronted with

the winged pear intending to symbolize, I was told, the composer’s soul ascending to heaven. Prior to our arrival in Honfleur, I’d also been told that the Satie House was a small museum that was unable to accommodate large crowds but was also one that could be visited in a relatively short block of time. Had it not been for a bite from the old hunger bug, I could have spent hours there.

Since all four of us seemed to be suffering from similar symptoms, we left the Maisons Satie turning onto Rue Haute whence we came. We’d passed La Fleur de Sel – a restaurant that William had recommended. I spotted the Michelin Guide plaque by the window and though it’s not a starred restaurant, it is a “Bib Gourmand” meaning good cooking and good value with prices under 40 euros. That description might well have been true but a glance at the menu showed that their prices weren’t far under that 40 € cap. The exchange rate at the time would have put us in the vicinity of $50 per person for lunch and I don’t think any of us wanted to spend that much especially given that we had an early buffet dinner scheduled on board.

We didn’t have to walk very far to find a place to our liking. In fact, it was the very next building where there was a restaurant called La Maison du Gouverneur. I ordered one of the classic regional dishes – moules frites. This isn’t fried mussels but is mussels steamed in a broth of white wine that’s been added to olive oil sautéed shallots and garlic. After the mussels have opened and been removed from the Dutch oven, creme fraiche, parsley, butter, chives, and mustard are added to the remaining cooking liquid and just as it starts to boil it is then poured over the mussels. This is served with French fries. It was homey, satisfying and, even with my beer, less than 20 €. It looked something (though not exactly) like this image taken from Trip Advisor.

And yet more music.

Why, you may wonder, were we having another buffet dinner? In essence, the reason for our second buffet was the same as the reason for our first. Tonight’s entertainment was not on board. Rather, we would be attending the closing night of the 22nd Festival de Pâques (Easter Festival) held in Deauville.

Deauville is about 40 km west of Le Havre (probably less than that as the crow flies but 40 km as the bus drives) so we had to be on our three buses in sufficient time to allow us time to reach the venue, walk through the drizzle to collect our tickets, and get settled in our seats.

The Festival de Pâques is a two-week celebration of chamber music held at the Salle Élie de Brignac which is an equestrian auction center that doubles as a concert venue. I’d estimate the capacity of the arena at perhaps 800 so it was unsurprising that, at some point in the seemingly interminable series of introductory thank you speeches and acknowledgments, someone mentioned our group of nearly 150.

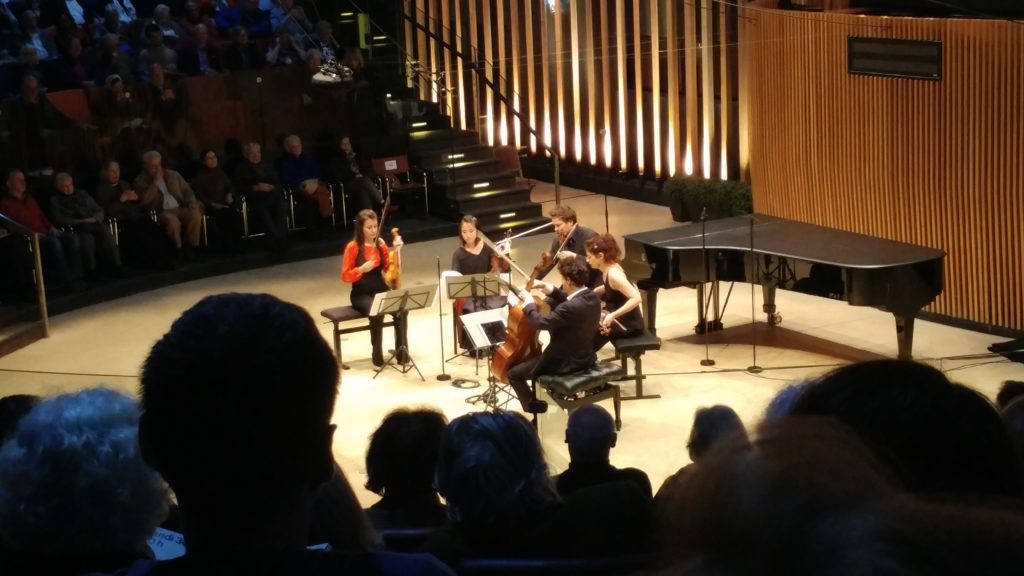

The festival features some very talented young musicians. In our case, we saw Liya Petrova and Mi-Sa Yang on violin, Adrien La Marca and Gabrielle Lafait playing viola, Edgar Moreau on cello and Adam Laloum, piano. The concert began with the Overture for String Quintet in C Minor by Franz Schubert.

(This is another phone photo.)

Another Schubert composition followed, the Fantasy in C Major for Violin and Piano. I was a bit surprised when Mi-Sa Yang, who was the second violinist in the opening quartet, stepped out as the soloist in the night’s second performance.

So appreciative of our group were the Festival’s organizers that they provided us a private intermission reception complete with a complimentary beverage and snacks. The final performance of the evening was Dvorak’s Piano Quintet Number 2 in A major. It was a splendid night of music and one that gave Jie and Tim a night’s respite.

And the answer is.

For those among you who are too young to understand the post’s title reference and who didn’t understand when I wrote this, “After the fall of Napoléon in 1814, the city again tried to resurrect it former position by trading in wood. It did so by turning to Norway and other parts of northern Europe” as a clue, your answer is in the video below.

(And thanks to D5 whose comment on what is now the first of three posts for this day for alerting me to replace the video I originally used.)

Next stop, Bayeux.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026