Église Sainte Catherine.

If you were to look for one characteristic that every European city shares, I’d suggest you need look no further than having a church as one of its most important buildings – if not culturally and historically – then certainly architecturally. Honfleur is no different but, at the same time, it is rather different.

Sainte Catherine’s church is a centerpiece of Honfleur but it also stands in stark contrast with the other churches we’ve visited thus far. Even if you merely skimmed the brief history in the previous post, it should come as no surprise that as this maritime town was batted back and forth between England and France during the Hundred Years War, the stone church that stood in the location of today’s Sainte Catherine’s didn’t fare too well.

The citizens of Sainte-Catherine’s Parish had to confront two shortages when they decided to rebuild the church after the disasters of the 15th century. The first was money. Although the town had periods of real prosperity, its economy hadn’t fully recovered from the combined ravages of the Black Death and more than a century of war. The other shortage was a lack of skilled workers, particularly masons, who could construct a stone church.

The solution? First, use wood. Second, use shipwrights. Wood was plentiful in the area and as a maritime center, many men in the town had significant shipbuilding skills that they applied to the construction of the church. The result? A church in the shape of an overturned double hulled ship that remains the largest timber-built church in France.

Another unique aspect of the church appears in this photo.

Although it didn’t require the prolonged construction of either Notre Dame (Paris and Rouen) we’ve seen, it was built in two distinct sections at different times. The first, or northern nave (on the right with the organ loft), used a model of a market hall and has the appearance of a reversed boat hull. It was completed in 1468. However, as the population grew, the parish needed a bigger church, so a second nave, with a vault consistent with modest Gothic churches, was added in 1496.

Outside, the church has yet another distinguishing feature – a separate bell tower. Perhaps due to a lack of expertise or perhaps out of a simple matter of practicality, the square framed bell tower topped by an octagonal pyramid was constructed above the bell ringer’s house. The external supports were added in 1718 and the church was declared a historical monument in 1879.

(Another photo I brightened from the original.)

The artistic side of Honfleur.

As you can see from the need to expand the Church of Sainte Catherine, late 15th century Honfleur was regaining its status as an important maritime center. By 1498 Charles VII wrote that it had “the largest and biggest supply of ships in Normandy” and by the middle of the 16th century the French writer François Rabelais used the port as the departure point of the giant Pantagruel for the Kingdom of Utopia in the first of his Gargantua series – Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes.

Perhaps its most famous ship owner, Samuel de Champlain, launched several expeditions from Honfleur including one in the spring of 1608 funded by Pierre Dugua de Mons. On 3 July of that year, Champlain landed at the “Pointe du Québec” where he built and fortified three buildings he called the Habitation de Québec thereby founding the Canadian city.

But the centuries weren’t always kind to Honfleur and its maritime ambitions. When France ceded control of Canada to England in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the thriving commercial trade between the port and Canada dried up almost immediately. The town turned to the West Indies and the slave trade but that lasted only as long as the First French Revolution and the rise of Napoléon. The continental blockade against the First Empire essentially ruined the city again.

After the fall of Napoléon in 1814, the city again tried to resurrect its former position by trading in wood. It did so by turning to Norway and other parts of northern Europe. (This should provide a clue to the title of this post. And if, perchance, you remain clueless, see the video that follows in the last post for this day.) This effort met with some success but the harbor began to fill with silt. At the same time, more modern facilities were being developed across the river in Le Havre and Honfleur’s maritime ambitions stagnated.

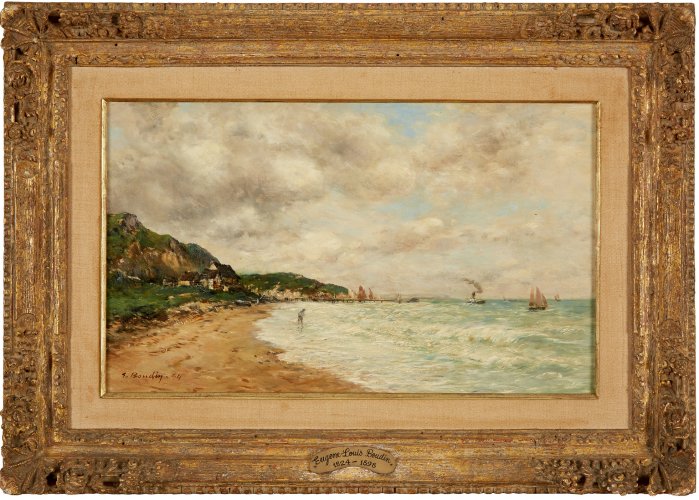

As the city once again struggled to redefine itself, a baby boy came into the world on 12 July 1824. His parents named him Eugéne. When Eugéne was 11, his parents moved to Le Havre and his father set up a picture framing and stationery business. By the mid 1840s a number of landscape painters – some English and some French – but all fascinated, as Monet would later be, by the rapidly changing light of the region began to frequent the Normandy coast. Several, including Jean-François Millet and Thomas Couture (who would later teach Latour and Manet among others) not only frequented the shop of the elder Boudin but often exhibited their work there as well.

The young and shy Eugéne Boudin, who had begun making pastel drawings of the countryside he loved, showed some of his work to these artists and Millet in particular encouraged him to pursue art as his vocation.

At age 26, Boudin earned a scholarship to study in Paris where he spent much of the remainder of his life. However, he not only returned often to his home region but with Alexandre Dubourg, another Honfleur born artist, established an artist’s colony close by the city – the Inn at Saint Siméon’s Farm.

The Inn made the area around Honfleur and Le Havre a regular gathering place for many artists of the time including Corot, Courbet, and a young Claude Monet who once said, “I owe everything to Boudin and I am grateful to him for my success.” Encouraged by the Dutch painter Johan Johgkind, Boudin was among the early practitioners and advocates of working en plein air and it would be fair to say that, for several decades, the best landscape painters of the time belonged to the “Honfleur School.”

(Anecdotally, there is good reason to believe that Marcel Proust used Boudin as one of the inspirations for Elstir – the artist in his magnum opus À la recherche du temps perdu {previously translated as Remembrance of Things Past and now more commonly – and probably more accurately – rendered as In Search of Lost Time. Almost certainly, aspects of Monet, Moreau, Vuillard, and especially Whistler influenced Proust’s portrayal of Elstir but he also presents the artist as an exceptional painter of the sea and sky in Normandy.

Camille Corot called Boudin “king of the skies” and Courbet, working by his side as Boudin painted Study of Clouds, Blue Sky is said to have exclaimed, “My God, you are a seraph, Boudin! You are the only one of us who really knows the sky!” Boudin is known to have closely studied the Dutch masters so Elstir’s death in front of a painting by Vermeer also hints at Boudin as a source of inspiration for the character.)

Thus, it’s safe to say that any visit to Honfleur should include a stop at the

Musee Eugéne Boudin where the town honors its native son.

This was the first place we went after finishing our walking tour that ended at Sainte Catherine’s church. We were joined by two Hawaiian friends – Becky and Linda – who were reuniting on the cruise since one of them had recently relocated to Texas. The four of us spent the rest of the day together. Though the rain had abated somewhat, inside was where we all wanted to be even if it meant only a brief museum visit. We arrived at about 11:00 and the museum closed at noon for a two-and-a-half-hour lunch break. (It was open from 10:00 to 12:00 and then from 14:30 to 17:30.)

In point of fact. it was a bit more eclectic than I expected. In addition to works by Boudin, Monet, and other Impressionists, there were paintings by some of the immediate predecessor painters who helped influence and inspire the “independents.” Equally interesting were the displays of antique toys from the 19th-century and the collection of tourist posters used to entice people to vacation on the Normand coast.

There’s yet another honored son of Honfleur and we’ll visit his museum in the next post.