Part two of this brief overview of Hungarian history ended with Lajos Kossuth ascending to a position of national leadership as an element of the Hungarian War for Independence. Part three will take us up to the end of the First World War.

Through the end of 1848 and into 1849, the Austrians suffered a number of military defeats and their government came to the edge of collapse. Then Emperor Franz Joseph 1 turned to the Russians for help and Nicholas 1 sent an army of more than 200,000 under a pact known as the Holy Alliance. By mid-August, the combined Austrian and Russian forces had won a series of battles at Segesvár, Szöreg, and Temesvár that effectively routed the Hungarians. They surrendered to the Russians at Világos (now Șiria, Romania).

One curious aspect to the end of the war in 1849 was the construction of the first permanent bridge across the Danube in Hungary – the Széchenyi Chain Bridge. This bridge, that would in 1873 facilitate the formal unification of the cities of Buda and Pest, still stands as an important icon and landmark in the city today. It’s seen here at night shot from the Buda side of the river with the palace in the background.

Compromise becomes a dirty word.

Failing to fully integrate the lessons of the 1848 revolutions, the Habsburgs, attempting to regain greater control over their empire, were at it again over the ensuing two decades. Their major conflicts in the Franco-Austrian War in 1859 (also known as the Second Italian War of Independence) and the Austro-Prussian War (1866) left them with a monumental debt and in a state of financial crisis.

Of course, the restive Hungarians continued pushing for their own independence and eventually, these factors resulted in the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. Because it had been negotiated by a small number of people and had less than favorable terms, many Hungarians viewed the Compromise as a betrayal of both the Hungarian cause and the heritage of the 1848-49 War of Independence. Its unpopularity led the government to use force to suppress civil dissent with the effect of creating deep and lasting schisms in Hungarian society.

One of the first items the Hungarians disliked was that, as part of the compromise, Hungary assumed a large part of Austria’s debt. This aspect of the Compromise was to be renegotiated every 10 years. This provision, combined with the different approaches the two regions undertook in dealing with their ethnic minorities, led to repeated constitutional crises within the Empire.

Under the Compromise, each region had its own government, headed by its own prime minister and it allowed for separate parliaments – one that convened in Vienna and one that met in Buda (later Budapest) that could enact and maintain separate laws for their respective regions.

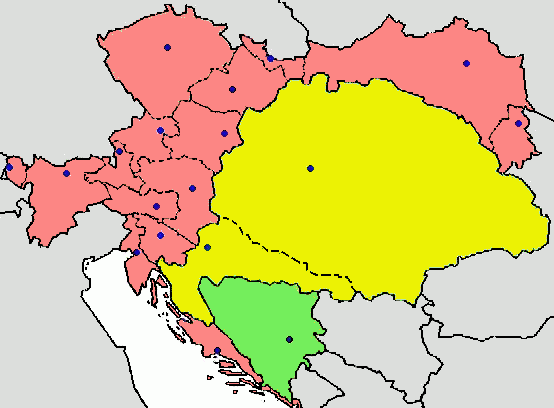

(Austria controlled the pink regions on the map above, Hungary the yellow, while the (I hope) familiar triangle of Bosnia and Herzegovina was jointly administered.) There was also to be a “dual monarchy” that consisted of the emperor-king, and common ministers of foreign affairs, defense, and finance. However, all of the latter were in Vienna with the Austrian king retaining royal privileges. The end result was a considerable reduction in Hungarian sovereignty and autonomy even in comparison with the pre-1848 status quo.

As I noted above, one of the ongoing sources of regional trouble sprung from the differing treatment of ethnic minorities within the two kingdoms. Perhaps because many Hungarians felt they had been coerced into accepting the Compromise, the government in Buda took a much more aggressive stance toward its minorities than was the case in Vienna. Several ethnic minorities, particularly Slovaks, Romanians, and Slavs faced intense pressure of Magyarization creating several nationalist and pan-nationalist movements within the kingdom.

Sensitive to this problem, Archduke Franz Ferdinand wrote a letter to his foreign minister in February 1913 that this irredentism would cease “if our Slavs are given a comfortable, fair and good life.” They weren’t and it didn’t. The irredentism culminated, of course, on 28 June 1914, with the assassination in Sarajevo of Franz Ferdinand which was then followed by the outbreak of the First World War.

The war raged for four years and, with the imminent defeat of the Quadruple Alliance or Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), the Hungarian government, with the agreement of King Charles IV (who was also Emperor Charles I of Austria), essentially gave what amounted to its two-week notice in mid-October 1918 and the Compromise formally terminated on 31 October.

End of Empires.

The end of the First World War effectively saw the end of four dynastic monarchies – Germany, Russia, Austro-Hungary, and the Ottomans. As we know, the armistice to end World War I was signed on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in the year 1918 (marked in the U S by the holiday known initially as Armistice Day and now called Veteran’s Day) but the full impact of the peace wouldn’t be felt in Hungary until the signing of the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. And, from the Hungarian point of view, this was yet another treaty about which there was little good.

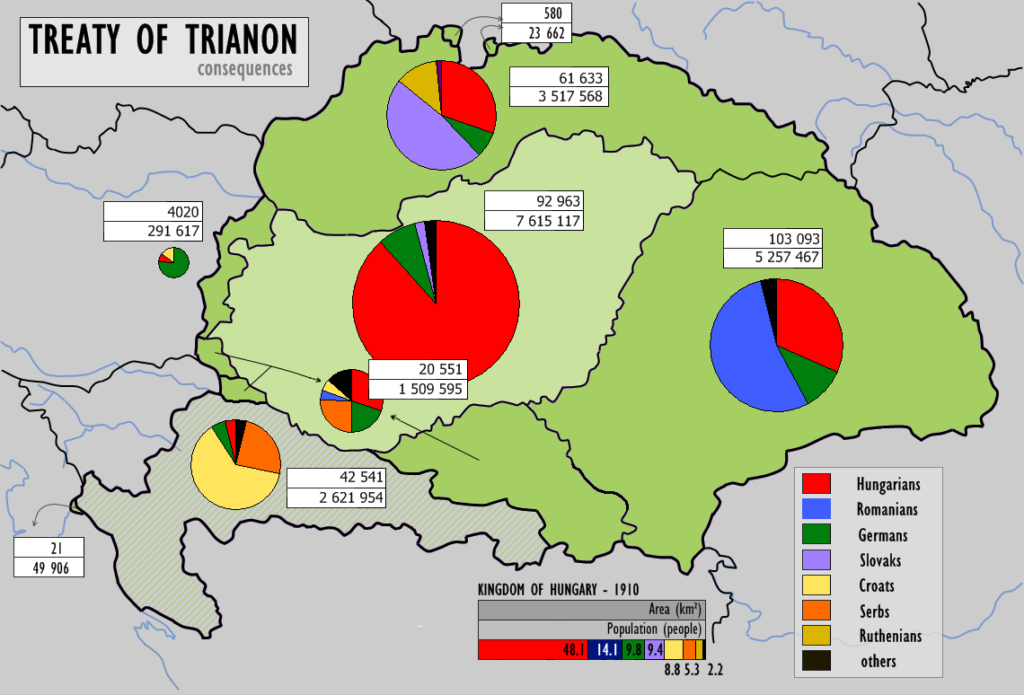

The treaty redrew borders creating a Hungarian state that was not only 72 percent smaller than the territory in the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary but left it a landlocked nation. The new Hungary lost 84 percent of its timber resources, 43 percent of its arable land, and 83 percent of its iron ore. The new borders also stripped Hungary of all its gold, silver, copper, mercury, and salt mines.

The treaty had a similar impact on the population which fell from 21 million before the war to about seven and a half million afterward.  Five of the Kingdom’s 10 largest cities, most notably Zagreb (now the capital of Croatia), Bratislava (the capital of Slovakia), and Romania’s third largest city TimiÈ™oara (Temesvár in Hungarian), were ceded to other nations. It left between 3,300,000 and 3,400,000 ethnic Magyars outside the borders of Hungary.

The dark green together with the grayish green area shows the Kingdom of Hungary under the Compromise before the Treaty of Trianon. The light green area is present day Hungary.

I’ll pause here and give you some time to digest this information before serving up a goulash of Hungary’s history from the end of the First World War to the present day.