After Patricia and I took our leave from our fellow OAT traveler, Alison, at the New York Cafe, I have neither notes nor a sharp recollection of anything we did. We probably meandered through the Jewish Quarter then back to the hotel to pack and chill out before dinner. Pat faced a bit of a dilemma. She had to decide whether she wanted to go to bed early and get a little sleep or simply stay up all night. Barbara had scheduled the airport transfer for her and the other three women to depart the hotel at either 04:00 or 04:30 Saturday. Life was easier for me in that regard because I was scheduled to leave at 06:30 so I’d sleep some regardless.

This Menza isn’t exactly a menza.

At some point, Pat and I set out from the hotel and began wandering up Andrássy Street. We didn’t need to go far – about two blocks – before we came to Franz Liszt Square (Liszt Ferenc ter). Crowded and lined with cafés on both sides of the central green area, it looked lively, interesting, and inviting.

We wandered up and down the square taking in some of the sites. One of several statues of the pianist and composer…

and the even more curious one of Liszt surrounded by musical instruments (and yes, that is, a Hooters in the background.)

one or more of the pianos that seem to be always present and available

and, of course, the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. (It was originally called the Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music and, from 1919 to 1925 the College of Music, before being named after its founder.)

(Liszt was born in 1811 in Sopron County in northeast Hungary bordering Austria. His mother Anna and his father Adam were both Danube Swabians.

{The Danube Swabians are among the many lesser-known ethnic groups that suffered greatly throughout much of the history of Hungary and the Balkans.

They were the earliest German settlers in Hungary and eventually grew to a population of more than 1,5oo,ooo. However, more than half of them lost their Hungarian nationality – being forced into Romania and Yugoslavia – after World War I when Hungary lost much of its territory.

After World War II, the 700,000 Danube Swabians still in Hungary, were classed as Germans, not Magyars. The Communist regime then used the census as a basis for their expropriation and deportation of Swabians from Hungary. When the deportations stopped, only about 250,000 Danube Swabians remained in the country.}

Liszt was itinerant. He considered himself somewhat Hungarian but also held on to his Swabian heritage. Since he never adopted the Magyar version of his name, we can’t be certain how deeply he identified with his Hungarian heritage. Hungary, however, has long celebrated him as its own – though not necessarily during his lifetime. In the early 1860s, some of Liszt’s Hungarian contemporaries attempted unsuccessfully to secure him some sort of permanent position in his putative homeland.

Finally, in 1871, Hungarian Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy, wrote to Emperor Franz Joseph 1 ultimately securing an annual grant of 4,000 gulden and the rank of Königlicher Rat or Crown Councillor for Liszt. In return, Liszt was obliged to permanently settle in Budapest, direct the orchestra of the National Theatre, and establish music schools and other musical institutions.

Despite those conditions, Königlicher Rat Liszt neither directed the orchestra of the National Theatre nor did he permanently settle in Hungary let alone Budapest. Typically, he arrived in the capital in mid-winter. Then, after one or two concerts by his students, he left by the beginning of spring. He never took part in the annual summer final examinations.

Liszt got himself in a bit more hot water in 1881 when he published a new edition of his book about the Romanis and their music in Hungary. According to this book, Hungarian music was identical with the music played by the Hungarian Romanis. He also made a claim that Semitic people had no genuine creativity and that they only ever adopted melodies from the country in which they lived. After the book was published, Liszt was accused in Budapest of spreading anti-Semitic ideas. It’s unclear whether he was truly anti-Semitic.

Liszt died in Bayreuth, Germany, on 31 July 1886, at age 74 while attending the musical festival there. His daughter Cosima was that year’s host. Just a few weeks earlier, his friend Camille Saint-Saëns had premiered his Symphony Number 3 [“Organ Symphony”] in London which he had dedicated to Liszt.

Still, the Hungarians hold him in enormous esteem. In addition to the named square and the music academy, there’s also a Franz Liszt Memorial Museum and Research Center on Vörösmarty Street just off Andrássy Street a block or so from the House of Terror.

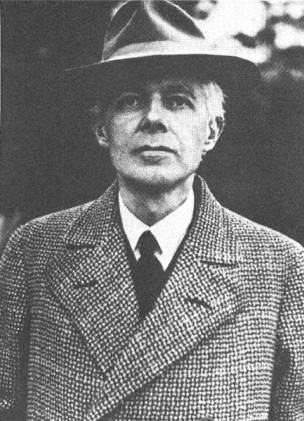

If you’re wondering where the honors are for Béla Bartók,

arguably the most famous Hungarian composer of the 20th century, they generally aren’t in Pest. Unlike Liszt, he was unabashedly proud of being Hungarian. He once said, “Throughout my entire life, in every aspect, at all times by all means I will serve only one objective: the benefit of the Hungarian Nation and the Hungarian homeland.”

So, why is it a bit harder to find honors for Bartók than it is for Liszt? First, you need to remember that because he was outspokenly anti-authoritarian and because his compositional styles and methods were equally unconventional, Bartók was a figure of controversy to the Communist government especially in its early, more dogmatic years. His anti-authoritarian streak had appeared years earlier as well. Bartók so strongly opposed Nazi Germany that in the early thirties he broke relations with his German publisher and refused to give any concerts there. Naturally, he opposed Hungary’s alliance with the Nazis thus losing favor with the collaborators who preceded the Nazis. Bartók emigrated to the United States in October 1940. He died in exile in New York in 1945.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, his reputation was slowly rehabilitated. Ultimately, as time passed he reached a status of supreme national eminence and, 45 years after his death, with the urging of his son Peter, his body was exhumed from its original burial site in New York and returned with great pomp and circumstance to Hungary where it was reburied in a single grave with that of his second wife, who had returned to Hungary after the war, his mother, and his mother’s sister – the people closest to him in life according to Peter.

Bartók now has a street named for him and the house he’d rented on Csalán Road before fleeing the country has been turned into a memorial museum. Both are on the Buda side of the Danube and some distance from the Castle District.)

Now, back to our dinner. After traveling the square from end to end, Pat and I decided to try the restaurant called Menza. As we’d done on our first night in Budapest, we had to negotiate for a table. Once we made it clear that we preferred eating outside, the negotiation proceeded more smoothly.

At the top of this section I wrote, “This Menza isn’t exactly a menza.” It’s probable that the proprietors chose the name with a deliberate sense of irony. The word menza translates as canteen and seems to be a cheeky reference to the canteens – particularly school canteens – of the Socialist era.

The full name is actually Menza Étterem és kávézó or Menza restaurant and café. According to its website it seeks to merge the savoir vivre of modern downtown restaurants with the relaxed atmosphere of Budapest’s 1960s coffee bars. They want their patrons in jeans to feel as comfortable as those who come in suits. The menu, like so many we encountered is eclectic and interesting and it includes both a non-traditional take on Hungarian veal stew and something as different from that as red tuna salad.

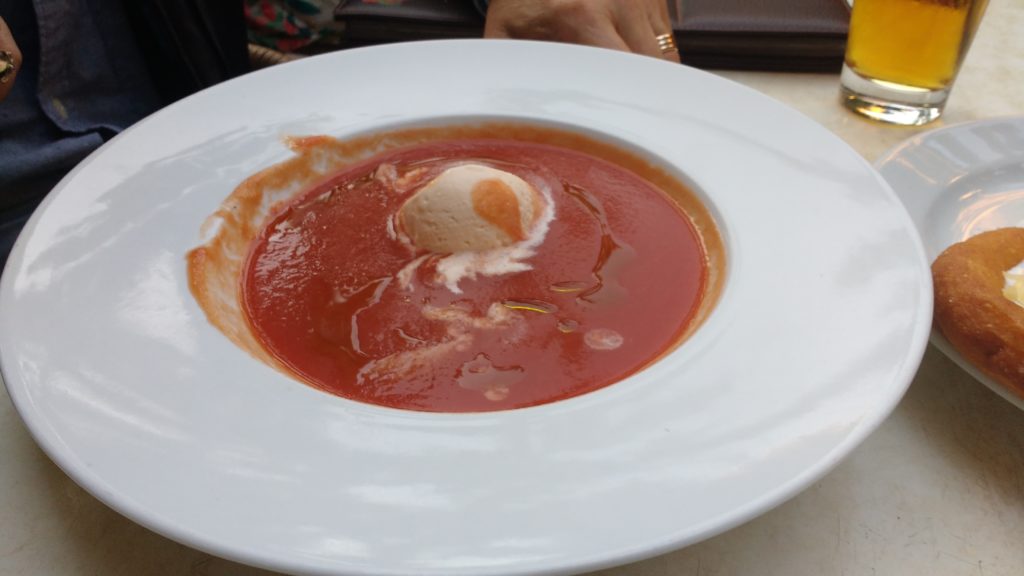

But Menza is widely known for its soups. The website We Love Budapest lists it among its “seven spots for supreme soup.” Menza’s regular offerings include goulash, a beef soup, “Garlic cream soup with traditional Hungarian fried bread topped with sour cream and cheese,” and “Pumpkin cream soup with cashew nuts and caramelized pumpkin.” It also offers seasonal soups. As I write this on December 15, the seasonal soups are “Tokaj wine cream soup” and “Traditional Hungarian fish soup with fish and offal.”

When Pat and I visited in August, one of the seasonal soups was (and I don’t have the full menu description) a tomato ice cream soup. Pat brilliantly managed a photo on her phone.

(That’s a glass of – white beer in the background and a bit of the “traditional Hungarian fried bread topped with sour cream and cheese” squeezing in on the right edge of the frame.)

(That’s a glass of – white beer in the background and a bit of the “traditional Hungarian fried bread topped with sour cream and cheese” squeezing in on the right edge of the frame.)

The end is night. A single post remains before I return home.

Note: In keeping with my 2022 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Thanks, Trina. The trip was a pleasure for me as well. Oh, and I love my cat, too.

Todd,

There is no way that I can ever commend and thank you enough for allowing us to relive this trip through your incredible blog. And not only relive it, but learn endless history and details that somehow escaped us despite all we absorbed while there.

You are an extraordinary historian and keen observer of your surroundings.

Again, thank you a thousand times!

You’re most welcome, Alison. I’m delighted you enjoyed reading the blog. I hope it communicated how much I enjoyed the travel

Thanks, great article.