This is the morning five of us leave on the post-tour extension to spend a few days in Budapest. Our reduced number meant that, for the first time since our arrival, we wouldn’t be traveling with room to spread out in a large 40-person bus but rather in a minivan that squeezed the five of us, Damir, and our driver into a much smaller space than what had become the norm. Damir’s job is to accompany us for the five-hour, 460-kilometer ride to the Hungarian capital, deposit us in our hotel, and hand us off to our local guide before returning to Zagreb.

We’ll head northeast from Ljubljana toward the Hungarian border about 215 kilometers away and leave Slovenia at “the beak of the chicken.” While Hungary doesn’t use the euro, both Hungary and Slovenia are part of the Schengen zone so customs and immigration are absent when you cross the national borders. However, even if you miss the “Welcome to Hungary” sign, other signs make it easy to know you’ve crossed into a different country.

Here’s how: All the challenges we native speakers of English encounter trying to wrap our tongues around consonant clusters (think words like ‘trg’) and nearly impossible diphthongs (think Ljubljana) pale in comparison to what we meet in Magyarország as the natives call Hungary. Still don’t believe me? Here’s the name of the town closest to our border crossing: Tornyiszentmiklós. Go ahead, say it. I dare you!

We stopped for lunch close to the border at a place where we could still use our euros. As noted above, Hungary still uses its historic currency rather than the euro and none of us had yet exchanged our euros or purchased Hungarian forints. We took our break at what looked to me to be the Hungarian equivalent of a truck stop except that it cost 50 euro cents to use the restroom – though you could then use the receipt to offset a purchase in the a la carte restaurant that had both a hot bar and a cold bar.

The terrain in this part of Hungary is flat so although we’ll have to drive 90 kilometers before the E71 highway begins its stretch parallel to Lake Balaton, we’ll be able to spot the lake on our left before then. Lake Balaton is interesting not only because its length makes it the largest lake in Central Europe but also because of its lack of depth. The lake is 75 kilometers long and will remain visible from the road for most of those 75 kilometers. Oh, and one of the places we’ll pass along the way is Szekesfehervar. Go ahead, say it. I dare you!

It’s apparently quite a popular getaway for Hungarians but has an average depth of only three meters and maximum depth of about 12 meters. For comparison, Lake Bled is only about two kilometers long but has a maximum depth of 30 meters. Nevertheless, since we’re riding parallel to the shore of the lake for about an hour and continuing for another hour or so before we reach Budapest, let’s take a look at some of Hungary’s turbulent history.

Plenty of agita to go around.

You might think that my persistent references to the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the entries from my time in the Balkans indicate that Hungary was a relatively stable part of central and eastern Europe. That’s not exactly the case.

The gent in the center of the picture above is Árpád. This is his place on the Millennium Monument in Heroes’ Square in Budapest. In one version of historical events, Árpád headed a confederation of Hungarian tribes and led them in a conquest of the Carpathian Basin that began at the end of the ninth century lasted into the early tenth. Although historians dispute his role, most Hungarians refer to him as the first founder of the Hungarian nation. The accuracy of Árpád’s legend notwithstanding, of one thing we can be certain, beginning on Christmas day in the year 1000 with the coronation of Stephen 1, who descended from one of Árpád’s sons, the Árpád dynasty ruled the Kingdom of Hungary for three centuries. (Stephen 1 is a double saint who received Catholic canonization in 1083 and Orthodox canonization in 2000.)

As has been the case previously, this won’t be an exhaustive course in Hungarian history so I’ll now skip ahead to the 13th century because it was a busy and eventful era. The first big news came in 1222 when King Andrew II was forced by his nobles to accept the Aranybulla or Golden Bull. Like the Magna Carta signed in England by King John seven years earlier, the Golden Bull placed constitutional limits on the monarch’s powers. Hungarian nobility now had the right to disobey the King when they deemed his actions contrary to law. The nobles and the church were also freed from all taxes, could not be forced to go to war outside of Hungary, and were not obligated to finance it. It’s also worth noting that point 24 of the Bull stated: “No Jew or Ismaelite can hold a public position. The Nobles of the Chamber, those working with monies, tax collectors and toll-keepers may only be Hungarian noblemen.” (Andrew had previously consigned the collection of the taxes and the administration of the royal mint to Jews and Muslims.)

In the middle of the 13th century Batu Khan, the grandson of Chinggis Khan, led the Mongol invasion of Europe. Although the Hungarians had some early success defending their land against the Mongols, they were thoroughly defeated at the Battle of Muhi in April 1241.

(THE MAP IS FROM THE WEBSITE SCOUT.COM).

The Mongols laid siege to the then capital Esztergom and succeeded in sacking the city on Christmas day forcing the rulers to relocate the capital to Buda marking the first time this city would serve as the Kingdom’s capital.

In a somewhat fortunate turn of events for Hungary and the rest of Europe (at least with respect to the Mongols), Ögedei Khan, who was the third son and second Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, died on a hunting trip in the spring of 1242. As one of the contenders for the throne, Batu Khan withdrew his armies and returned to Asia. Although his withdrawal left much of eastern Europe depopulated and in ruins, the Magyars learned one important lesson. The countryside might have been destroyed but the forts and fortified cities had survived.

As a result, beginning with Béla IV, who was declared the “Second Founder of the Homeland,” the Kings donated more royal land to the local magnates during the 13th and 14th centuries with the condition that they build forts not only on the borders but also inside the country.

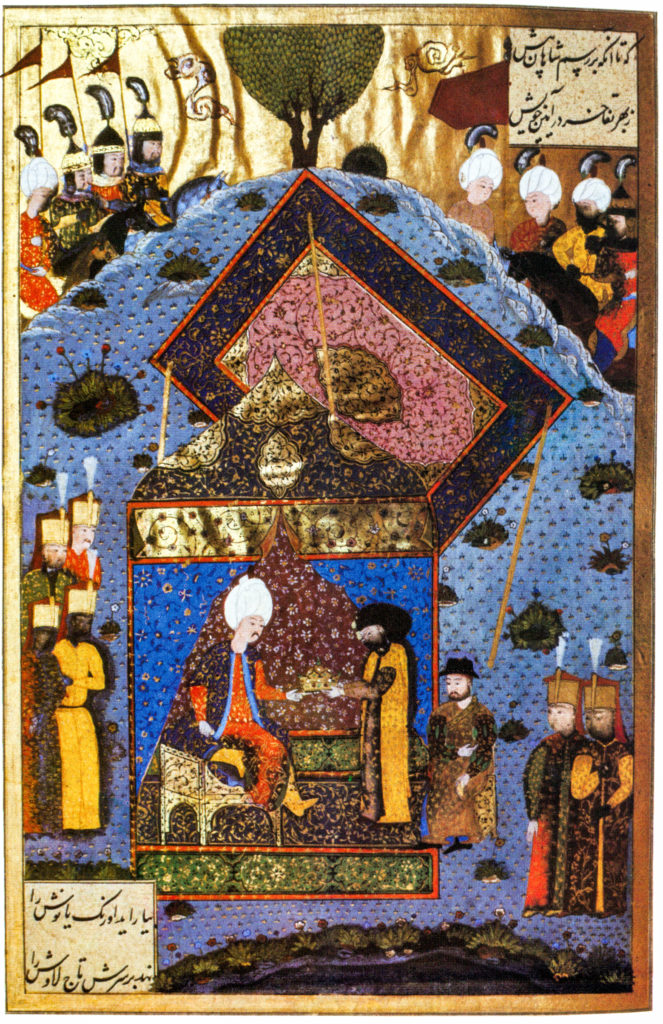

Leaving the newly fortified Hungary behind us, we’ll make another temporal jump and land in 1526 when Suleiman the Magnificent crossed the Danube into Hungary. Somewhat surprisingly, he met virtually no resistance. Hungary’s king at the time was Louis II and he had planned to send a vanguard to hold the Danube where the Ottomans were expected to cross. However, the nobles, under the power granted to them by the Golden Bull three centuries earlier, refused to follow the King’s deputy into battle saying they would only follow the King himself. This might not have been the wisest choice.

With Suleiman’s army advancing toward Buda, Louis mustered a force of 26,000 to meet an Ottoman army at Mohács that was four times as large. Although territorial familiarity gave the native forces some early successes in the battle, the superior numbers and fighting skill of the Ottomans ultimately decimated Louis’ army and killed the King, who was barely 20 years old and had no heirs. Suleiman then installed Janos (John) Zápolya as his vassal King of Hungary. (A note about Hungarian names. The personal form of Hungarian names traditionally places the surname first. So original sources are likely to record names as Zápolya Janos or Kossuth Lajos – a name we’ll encounter later in this history. I’ve chosen to westernize this by placing the given name first.)

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

The capacity for war in Europe is daunting. Great job of condensing what is no doubt exhaustive detail… thanks, Todd

And as you read on, I hope you’ll understand the reason I’ve delved into all this history.