Gyula Andrássy.

The posts I wrote about Hungarian history while lengthy in combination were far from comprehensive. Among the influential Hungarians I haven’t discussed is Gyula Andrássy – honored by the statue in the photo at the end of the previous post.

[Photo from Wikipedia – Public Domain].

In his youth, Andrássy was a strident advocate for Hungarian independence and sovereignty. During the 1848 Revolution, after serving with distinction in several battles, he became the adjutant to Artúr Görgei who commanded the Army of the Upper Danube. He served with distinction though the Hungarians did eventually surrender to the Russians at Világos and it never helps being on the losing side.

A self-imposed decade long exile in London and Paris, rehabilitated his reputation and he was chosen vice-president of the Diet late in 1865 after his return to Hungary.

The next year he was elected as president of the sub-committee that drew up the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. On 17 February 1867, Emperor Franz Joseph appointed him as the first prime minister of the Hungarian half of the newly formed Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary a post he held until 1871 when he became the Foreign Minister for the combined kingdom. It’s safe to say he earned his statue and its place by Parliament.

As we continued onto Kossuth Square, we came to one of two recently opened underground memorials there. The first honors the events of October 1956 detailed in this history post.

When construction of the Parliament building was completed in 1904, it used a unique cooling system. A water tower across the street fed cold water into two long tunnels underneath the building. The water then cooled circulating air that, in turn, cooled the building. By the 1920s air conditioning came to Parliament and the tunnels were neglected then sealed.

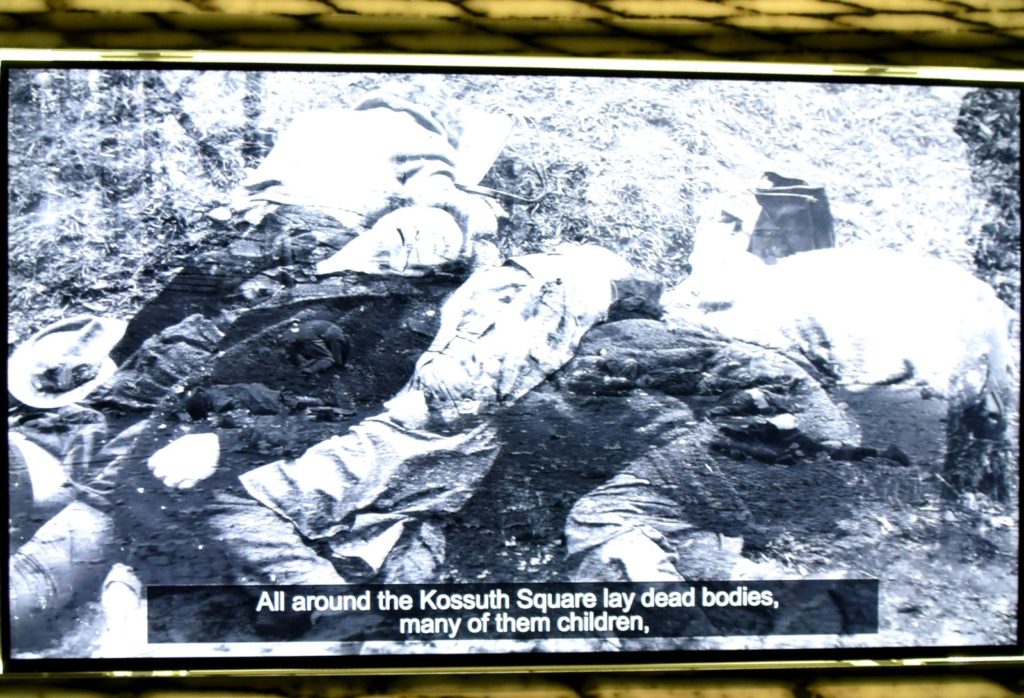

Earlier this decade, Parliament and Kossuth Square underwent extensive renovations that were completed in 2014. In the process, the reopened tunnels were converted into a pair of museum spaces. As we approached from the south, we came first to the Memorial to the 1956 Massacre on Kossuth Square. Because of the chaos of the moment no official fatality count exists and the estimated range of deaths is exceptionally wide – ranging from as few as 22 to as many as 1,000. The likely number is probably close to 500.

A set of stairs leads to the tunnel

where a series of photos, holographic projections, and films document the turmoil of those days from the early almost celebratory moments

to the horror of the slain,

before ending at a memorial for the victims – nearly all of whom are unknown.

[Many of these photos are taken from the blogsite “Cleared and Ready for Takeoff.”]

The north tunnel is a lapidarium. Parts of Parliament’s façade were removed during the renovation and are preserved and presented here. The display contains about 80 statues and ornaments as well as different stone, metal, and ceramic building blocks – many of which came from the roof of the building and show traces of the effects of Budapest’s weather.

You enter the lapidarium by descending a stairway similar to the one on the south side. And, as you can see, excepting the track lighting, the tunnel itself looks much the same.

[Photo from Daily News Hungary.]

In addition to the stonework, the lapidarium presents a pictorial history of Parliament and the square. Here’s an up-close look showing how the figures had eroded.

Here are a few other notable elements of Kossuth Square.

First, opposite the Parliament is the former Hall of Justice building. Hungary held an architectural competition to design the Parliament which was won by Imre Steindl. The design used for the Hall of Justice was submitted by one of the other architects in the competition. Today, it houses the Ethnographic Museum.

A statue on the Square’s south end honors Ferenc II Rákóczi who led the 1703 independence war.

Just past the far southeast corner of Kossuth Square is a monument honoring Imre Nagy. In it, Nagy is looking toward Parliament as though he was still looking out for the well-being of the Hungarian people.

You might think that the memorial on the north end – honoring the man whose name graces the square – would be the subject of little to no controversy. But such is not the case. In fact, more than one monument honoring Lajos Kossuth has occupied the space. The first, designed by János Horvay, was installed in 1927. He placed Kossuth in the center of the memorial flanked by eight members of Hungary’s first Diet. Critics at the time called it “pessimistic” and Mátyás Rákozi ordered it dismantled in 1950.

Rákozi then engaged Zsigsmond Strobl to model a new monument. Unveiled in 1952, Strobl depicted Kossuth as an orator with his hand outstretched pointing toward a better future. He was flanked not by eight other politicians but rather by members of the proletariat.

When the current government decided to renovate the square, they opted to replace Strobl’s work with a reproduction of Horvay’s original. For a time, Kossuth stood alone but now, the memorial appears much as it did in 1927.

Next we can move on to Parliament itself.

Maybe not the best but definitely the biggest (at least it was).

In a previous entry describing my adventures in Pest, I mentioned taking the Metro Yellow Line to one terminus at Vörösmarty Square. That square’s name honors the 19th century poet and playwright Mihály Vörösmarty. I note this because, in addition to being considered one of Hungary’s great poets, Vörösmarty also served as a member of the Diet for a brief time in 1848. Although parliamentary sessions were held in Bratislava until being moved in 1843 to what was called at the time Pest-Buda, the itinerant Hungarian Parliament had no permanent home. At one time, Vörösmarty lamented, “The motherland does not have a house.”

Nearly three decades later, the government was finally able to authorize the construction of a parliament building. (Remember, one element of the Compromise of 1867, gave Vienna control of the purse strings.) The process began in 1880 with a competition for the building’s design. Nineteen architects entered the competition and Steindl won the competition with a Gothic Revival design inspired by the English Parliament. (It might have helped that one of the judges, Gyula Andrassy, had spent considerable time in London and admired that particular structure.) Once again, considerable time would pass between the declaration of Steindl’s winning design and its ultimate realization.

Like its counterpart in London, the building’s appearance is even more dramatic, impressive, and perhaps iconic when viewed from the riverside.

The cornerstone was laid in October 1885 and construction proceeded slowly, taking 17 years to complete enough of the building for the first session held there in 1902. (The building wasn’t fully complete until 1904.) Like any self-respecting government project, it required the use of only Hungarian materials and resources whenever possible. (This included the use of limestone that, as the figures in the Lapidarium clearly demonstrate, was not well-suited to withstand the extremes of Budapest’s weather.)

And, like any typical government project, it encountered some cost overruns. The initial estimate to complete Steindl’s plan was 18,500,000 golden crowns. By the time they finished the project, the total actual cost was 38 million gold crowns.

Students of architecture will note that Steindl’s design doesn’t rigidly conform to Gothic Revival particularly regarding the central dome – a structure rarely used in Gothic buildings. The interior, even more stylistically mixed, is perhaps better termed historical eclecticism.

The symmetrical building, with two identical legislative halls, is 268 meters long and 123 meters wide. It has 691 rooms and 20 kilometers of stairs. The spire on top of the dome reaches 96 meters – the same height as the top of Saint Stephen’s Basilica and serves as a symbolic reference to the nation’s founding in 896. At the time of its completion, it was the largest parliament building in the world. (It has since been surpassed by the Romanian Parliament in Bucharest and the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.) It’s typically considered to be among the world’s most beautiful legislative buildings.

And that assessment applies not only to the outside. Visiting Parliament is both easy and challenging. Pat was wise enough to negate the challenging aspect when she purchased tickets in advance via the online portal that included a 45-minute guided tour. Otherwise, we’d have likely confronted the long ticket lines in the perpetually crowded Visitor Center.

As I noted above, the interior of the Hungarian Parliament is architecturally eclectic. In addition to Gothic, there are also elements of Renaissance and Baroque styles. For example, the dramatic main staircase,

which leads to the interior of the hexadecagonal (16 sided) dome,

in which you can see the Holy Crown, Orb and Scepter.

Of course, the building is also known for spectacular stained glass

and hundreds of statues that line the halls.

In some ways, it’s a lot to see in just 45 minutes. In other ways, 45 minutes is just enough.