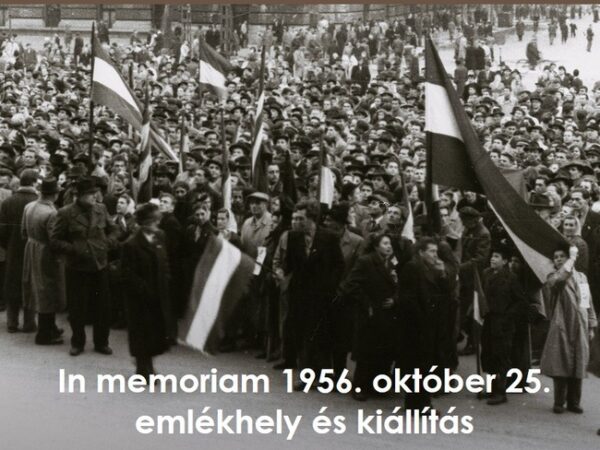

The previous post ended with the eruption of chaos and violence among the demonstrators in Kossuth Square, the AVH, and the Soviet Army. As reports spread about the events in Budapest,

[Photo From Museum of the Hungarian Parliament].

so did the uprising spread into the countryside. Sensing an opportunity, some sympathetic Soviet units actually worked with the protesters. Most, though, worked to quash the rebellion. Negotiating behind the scenes, Nagy announced a cease fire during the afternoon of 28 October. In his speech, the Prime Minister promised unconditional amnesty for all parties and called the protest a “great, national and democratic event.” He also promised to disband the AVH, the immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops from Budapest, and to enter negotiations for the withdrawal of all Soviet forces from Hungary.

Somewhat skeptical of Nagy’s ability to fulfill his promises and craving greater independence, the under-armed and undermanned Hungarians had continued fighting believing promises of forthcoming Western support that were being broadcast over Radio Free Europe. On the first of November, Nagy announced Hungary’s withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact and adoption of a stance of neutrality similar to that of Austria. This decision likely precipitated a more determined response known as the second Soviet intervention.

The Hungarians fought on but the expected western help never came and on 4 November, bolstered by the West’s indifference, more than 150,000 Soviet troops and 2,500 tanks entered Hungary violently suppressing the opposition, killing more than 20,000 Hungarians, and imprisoning even more. An additional quarter million Hungarians fled the country in a matter of days before the Soviets were able to close the borders.

In the immediate aftermath, Nagy was given sanctuary in the Yugoslav embassy. János Kádár, who was now the General Secretary of the Hungarian Workers’ Party and had been installed with Soviet support, gave Nagy a written guarantee of free passage but the former Prime Minister was arrested anyway – though probably without Kádár’s knowledge or approval. He was spirited away to Romania for three years before being covertly returned to Hungary where, under orders from Nikita Khrushchev, he was secretly tried and executed in June 1958. Meanwhile, Kádár would rule Hungary for the next three decades.

Goulash Communism.

It’s likely that Krushchev, in ordering the Soviet Union’s intervention coupled with the ruthless actions taken to crush the 1956 rebellion in Hungary, intended to demonstrate to the rest of the Soviet Bloc the futility of such rebellions. Khrushchev made it clear that Kádár was his handpicked successor to Nagy. However, the new leader proved to have something of a reformist and independent streak.

(This 1962 photo of Kádár is from the Dutch National Archives.)

To begin with, Kádár was far more collaborative in his decision making particularly when compared with the authoritarianism of Rákosi. After he felt he had stabilized both the internal political situation and Hungary’s relationship with the Soviets, Kádár declared a general amnesty in 1963 and freed most of the individuals who had been imprisoned for their participation in the 1956 uprising.

Kádár continued his moderate policies and reforms in Hungary over the ensuing few years. As Khrushchev’s health declined in the early sixties distracting the Soviets from the situation in Hungary, he saw an opportunity to declare that the foundations of a socialist society had been laid and began a bolder series of economic and social reforms that came to be known as Goulash (pronounced goo-yahsh) Communism.

While far short of Western norms of acceptability, relative to other countries within the Soviet sphere of influence, Kádár gradually opened up press and speech freedoms, allowed more open borders, eased restrictions on cultural activities, and reined in many of the excesses of the AVH – though they were still active as a mechanism of control and generally feared by the citizenry.

Economically, he permitted more trade with the West, granted farmers on the cooperative farms the right to have large private plots of land, allowed some small private service sector businesses to operate and opened the country, in a measured and limited way, to the integration of market forces. This led Hungary to a higher standard of living than nearly all the other countries of eastern Europe. Interestingly, while Kádár’s more flexible style of Goulash Communism focused on the material well-being of Hungary’s citizens, Kádár himself maintained a quite modest lifestyle eschewing the indulgences of many of his counterparts across the communist bloc.

The recession of the 1980s saw a decline in Hungary’s standard of living and, as his health began to fail, Kádár resigned in 1988. He died less than a year later. At the same time, communist regimes all over Europe had begun to fall apart and Hungary was no exception. On the other hand, perhaps because of the groundwork laid by Kádár, Hungary’s transition from communism and one-party rule to capitalism and a multi-party democratic system was quite peaceful. The body of Imre Nagy was exhumed and his reburial in June 1989 is considered by many as the symbolic end of communism in Hungary.

[Photo From Europe Between East and West].

Its actual end came in May 1990 with the nation’s first truly free elections resulting in József Antall, the head of the conservative Hungarian Democratic Forum, becoming Hungary’s first democratically elected Prime Minister since World War II.

However, although peaceful, the transition has been far from facile. In 1991, the removal of state subsidies and rapid privatization of businesses coupled with the global recession contributed to a severe economic downturn in Hungary. Austerity measures instated by Antall’s government proved exceedingly unpopular resulting in the election of the Communist Party’s legal and political heir, the Socialist Party, in the subsequent 1994 elections. These rather abrupt shifts in the political landscape were repeated in 1998 and again in 2002. Each electoral cycle resulted in the governing party’s ouster and the election of the erstwhile opposition.

The continually shifting policies have likely contributed to the country’s inability to meet the Maastricht criteria that would permit it to adopt the euro as its currency. Despite indications that adopting the euro would significantly increase foreign investment, current Prime Minister Viktor Orbán declared as recently as June of 2015 that his government will no longer entertain the idea of replacing the forint with the euro in 2020 which had been the most recent target date.

On the other hand, like most other post-communist European states, however, Hungary broadly pursued an integrationist agenda, joining NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004. Though it’s part of the Schengen Zone allowing for the free movement of people, Orbán has been staunchly isolationist in his response to the current refugee crisis enveloping Europe but exploring that situation would require a much longer discussion.

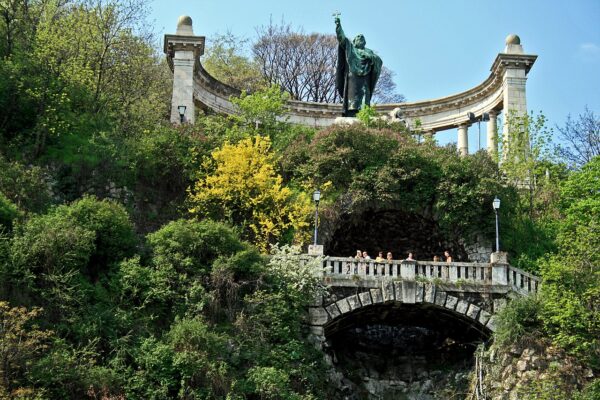

Fortunately, moments ago the bus passed under Gellért Hill

[Photo From Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

and crossed the Danube into the Pest side of the city. We’ll arrive at our hotel in a few minutes and you’ll be spared my analysis of the refugee crisis. After all this history, we’re finally ready for the fun part – visiting the beautiful and intriguing city of Budapest.