Most of the sources I’ve read indicate the presence of First Nations along the Canadian Pacific coast and inland into what is now British Columbia dates to 10,000 years BP. However, given what we’ve learned about the Bering land bridge and the rapid population of other parts of the Americas millennia earlier, I think it’s reasonable to assume that some of the migrants found the area’s geography and natural abundance enticing enough that they would have settled the area soon after their arrival and it would be unsurprising if older artifacts turn up.

Let’s not get too Squamish about it.

The area in and around Vancouver was the traditional territory of the Coast Salish people – a group of ethnically and linguistically related indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast – of whom the Squamish are but a single tribe (but good fuel for a bad pun). They certainly inhabited (and still do) the land in and around Vancouver.

[From Wikimedia Commons Map created by OldManRivers in 2012.]

However, because there’s a greater depth of information available concerning the “parent” group, it is the Coast Salish who will be the focus of this post. In a broad sense, the Salish occupied the territory shown on the map below.

[Map from Canadian Encyclopedia.]

The map above delineates the traditional territories of the five main groups of First Peoples in British Columbia. Although there may have been as many as 70 distinct subgroups, linguistic and cultural similarities have allowed anthropologists and historians to construct these five major groups with each referring to a language family. It should be noted, however, that two widely separated branches of Salishan languages developed – Coastal and Interior – and we must also take this into consideration when thinking about these people.

Like all people of their time the earliest arriving groups in the Pacific Northwest organized their societies around hunting and gathering. In this geographic region the most important resources came from the ocean – salmon, shellfish, octopus, herring, crabs, whale, and seaweed – and the surrounding forests – with a primary focus on cedar. Although they were slow to develop an agricultural economy, the abundant resources allowed them to build more permanent settlements at an earlier date than their eastern Canadian counterparts.

Generally constructing permanent settlements close to the navigable water the Coast Salish lived in these villages during the winter after spending the summer gathering and storing food. They lived in large shed-roofed houses, built from cedar and sometimes referred to as plank houses.

[Photo from Canadian Encyclopedia – Artwork by Gordon Miller.]

Life on the Coast.

The Coast Salish are well known for their art. House posts and design motifs featuring Northwest Coast animals and spiritual beings are prominent in their art works. Although totem poles are the most renowned feature of Northwest Coast indigenous people, decorative artwork was also part of daily life. It’s not uncommon to find embellishments on tools, houses, baskets, and clothing.

Like most of the Northwest Coast people, the Coast Salish built their society primarily around a large group of kin who usually shared common ancestry with a principal difference being that in the north kinship was established almost exclusively matrilineally while farther south kinship ties could be a bit more fluid and were considerably less rigid among the Coast Salish than their northern neighbors.

With a core of close kin living together in a house (such as the one seen above) or house cluster, the Coast Salish had a hierarchal society centered around real and tangible property. This formed the basis of the Northwest Coast system of rank and class. A distinction between the upper and lower classes was universal, as was the institution of slavery. Slaves were acquired in war or by purchase. Although limited in scale and scope, war and armed conflict appears to have been rather commonplace – often motivated by the acquisition of property including slaves.

Some groups engaged in contracted marriages between people of different kin groups. These marriages, often between groups in widely separated villages, served to validate lineage rights and maintain class position. People from many kin groups convened to witness claims at potlatches. At these ceremonies, hosts would feed and distribute gifts to guests.

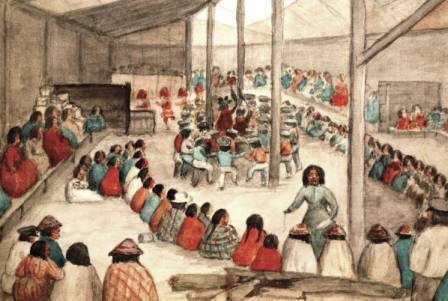

[Image of a potlach from Alchetron.com.]

In addition to this more secular function, the potlach could also serve a sacred and spiritual purpose. Spirit helpers conferred songs and masked re-enactments depicted legendary or supernatural events. Many archaeologists believe that artistic and spiritual traditions like the potlatch have been practiced on the Northwest Coast for over 5,000 years.

The White man cometh.

You might have noticed in one of the geological posts that I wrote about the Juan de Fuca Plate and (being fairly certain he wasn’t a ceramic artist) wondered who he was and why a plate – even a small tectonic one – bears his name. Juan de Fuca was a Greek (Ιωάννης Φωκάς) maritime pilot in the service of King Phillip II of Spain and if you look at a map, you’ll see the strait between Vancouver Island and the Olympic Peninsula also bears his name. If his claim that he was the first to explore this area in 1592 is true, then it’s likely that he was the first European to contact the Salishan people. (There is some countervailing evidence that England’s Sir Francis Drake sailed this area in 1579.)

As they did with the indigenous people of Southern California, however, the Europeans appear to have left the Northwest Coastal people alone for the next century and a half or so. However, as European Canada moved westward, its consequences were no less violent or deadly for the indigenous people. While it’s probably true that they, like so many elsewhere on the continent, were killed in the largest numbers by European diseases such as measles, smallpox, and influenza for which they had developed no immunity, they also suffered at the hands of armed settlers and soldiers and from factors directly connected to colonialism – land theft on a gigantic scale, forced removals, and the overuse of natural resources.

Although the 1763 Treaty of Paris made no mention of Indigenous Peoples of North America, a Royal Proclamation by King George III, did. It established a firm western boundary for the colonies making all the lands to its west “Indian Territories” where there could be no settlement or trade without the permission of the Indian Department. Some have interpreted that the original intent of the Royal Proclamation was to slow uncontrolled western expansion of the colonies and control the relationship between First Nations and colonists. It didn’t work out that way for the First Nations.

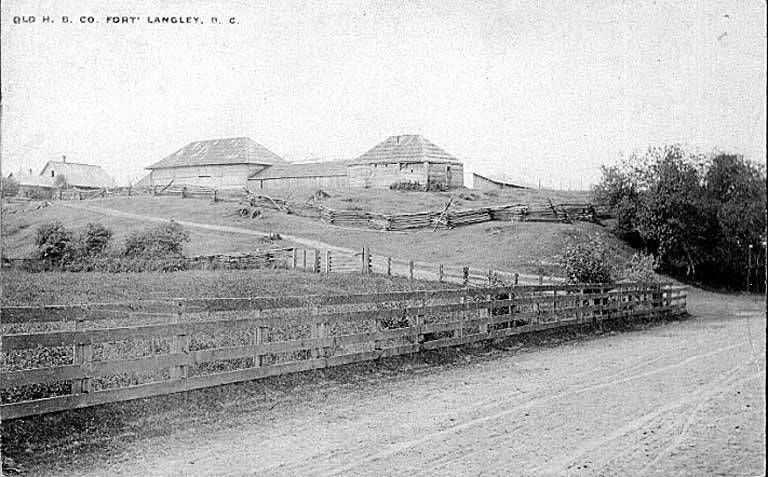

As early as 1827, the Hudson’s Bay Company established its first trading post in Coast Salish territories at Fort Langley.

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

As more settlers arrived, Coast Salish peoples were increasingly displaced and were decimated by smallpox epidemics in the 18th and 19th centuries. From 1850-1854 in a series of “treaties”, commonly known as the Douglas Treaties (named for the Governor of Vancouver Island James Douglas) Indigenous Peoples forfeited their title to the land in exchange for clothing, cash, and other goods likely with little understanding of the nature of the transaction. Today, only an estimated 56,000 Coast Salish remain living in the United States and Canada.

I’ll close today’s post with a song that’s likely familiar to most of you. It’s sung in hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ – a down river or island dialect of the Halkomelem language which is part of the Coast Salish language group. I hope you enjoy it.