Prologue.

Before I start in earnest, let me brush aside the controversial hypothesis that the first humans arrived in California some 130,000 years ago. In 2017 a group of researchers looking at the remains of a mastodon and other material that had been uncovered in San Diego County some 15 years earlier claimed that, “the rocks showed clear marks of having been used as hammers and an anvil. And some of the mastodon bones as well as a tooth showed fractures characteristic of being whacked, apparently with those stones.”

I’m disregarding this analysis for two main reasons. First, the evidence is thin and still quite controversial. Second, even if unimpeachable evidence is uncovered it has no bearing on the first human settlers not only in Southern California but in the Americas as a whole. As measured by mutations in the genome of Native American populations, their first common ancestor lived some 20,000 – 30,000 years ago thereby rendering even the possibility of this earlier group irrelevant because their genes are extinct. With this out of the way, let’s take that earnest look.

California Dreamin’ (Maybe. Maybe not.)

Although substantial evidence, including the skeleton of a woman on display at the Page Museum who is believed to be the only human trapped in the La Brea Tar Pits, points to human habitation in the area of California that today comprises Los Angeles and Orange Counties and the offshore islands of Santa Catalina and San Clemente for 7,000 years, there’s little knowledge of their point of origin.

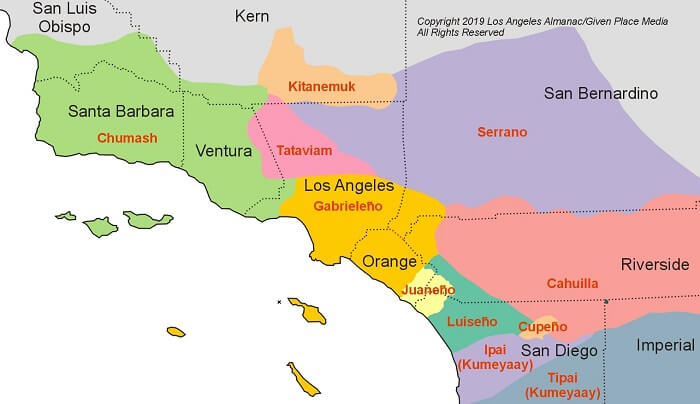

[Map from L A Native AmericanCommission.]

As yet, neither genetic nor linguistic analysis has provided an answer. (While the map above identifies this group as Gabrieleño – the name forced upon them by the Spanish when they built the San Gabriel Mission – I will refer to them as Tongva which is an anglicization of their tribal name.)

Not only do they bear little physical resemblance to the people that settled in the American Great Plains there is likewise no evidence of shared linguistic, religious, or cultural connections with these nations. (Please read the special supplement that follows to learn more about the native religion of the Tongva.) We are thus unable to even speculate about the reasons these First People settled in this area. We do know these early arrivals found the gentle climate for which Southern California is so well known today. Although the lack of rain inhibited any significant agriculture, the soil was rich enough (recall the alluvial deposits carried by the streams eroding the San Gabriel Mountains) that by skillfully harvesting and processing wild nuts and berries, hunting small to medium sized game such as rabbit and deer, and fishing in the abundant rivers and ocean that the area supported a relatively large and healthy population.

The Tongva were semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers who roamed an area of approximately 4,000 square miles (10,350 square kilometers) while typically settling for periods of time in easily assembled and disassembled villages of about 50 families although the largest of these could grow to encompass 500 or 1,000 people.

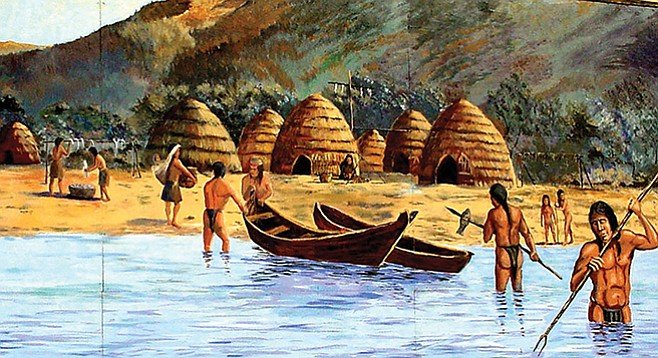

Those who lived close to the coast or on the channel islands constructed conical homes using a combination of clay, whale bones and tule (a giant species of sedge) while those living farther inland were more likely to use arrow weed and croton with the clay.

[Image from San Diego Reader.]

The coastal people were also known for crafting plank canoes called tomols by seaming together planks of cedarwood with sinew and pitch. These seaworthy boats could be as long as 24 feet (7.3 meters) that allowed communication and trade up and down the coast and with those who inhabited the islands. A secretive guild of craftsmen built the vessels.

Each village was ruled by its own tomyaar or chief. Tongva Indians regarded marriage as a diplomatic arrangement that strengthened trading and security needs between villages. This contributed to making marriage an economic relationship, which underscored the importance of women in tribal society. Larger Tongva society was organized under a hierarchical structure in which the elite group of chiefs, their families and any other families who were successful within the village as artisans (or craftsmen who built tomols), hunters, or traders sat at the top. There were also clear middle and lower classes.

No one here but us Indians.

For thousands of years the native people of California were able to maintain relatively stable and peaceful relations. Resources were plentiful and the topography of the state – marked by mountain ranges and deserts, made it difficult for the indigenous groups to travel great distances. This isolation alone was sufficient to inhibit belligerent interaction. The small map section above shows 11 different tribal groups and some anthropologists believe that these divided and isolated people could be identified by as many as 135 different languages or dialects.

The first known contact between Europeans and the tribes of California occurred when Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo – a Portuguese sailor exploring on behalf of Spain – sailed up the west coast of North America in 1542 but it had little impact on the native tribes.

[U S Postage Stamp – 1992.]

Two elements conspired to leave the California natives undisturbed by Europeans for more than two centuries. Cabrillo reached Santa Catalina Island on 7 October where he and his crew “befriended” the resident natives before continuing the journey northward – at least as far as Point Reyes and perhaps as far as the Russian River. On 23 November 1542, the little fleet arrived back at Santa Catalina Island planning to spend the winter there and make repairs. Sometime around Christmas a group of native Tongva warriors attacked a group of Cabrillo’s men. Cabrillo stumbled stepping out of his boat and splintered his shin. The injury became infected and gangrenous. He died on 3 January 1543.

The second element was that Cabrillo’s men reported that they had found no valuable metals, only “more poor Indians.” So, although the Spanish claimed the territory at the time of Cabrillo’s voyage, facing a captain’s untimely death and no valuable resources to exploit or plunder it appears they were content to leave the “poor Indians” alone.

The eighteenth century – change is coming.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Spain had well established positions throughout Mexico and in 1769 King Carlos III ordered new land and sea expeditions from there to California. These expeditions included military troops and Franciscan missionaries. One of those missionaries, Father Junipero Serra, established Mission San Diego de Alcalá – the first of 21 Spanish Missions – on 16 July 1769. A drought in 1774 prompted the fathers to move the mission from its original location on a hill overlooking the bay to its present location where the Spaniards were met with strong resistance from the local Tipai-Ipai tribes. (See map.)

The conflict between the Spanish and the natives stretched on until 4 November 1775 when hundreds of local warriors attacked the mission, severely damaging the structure and killing the mission’s head priest Father Luis Jayme who became California’s first Catholic martyr. When the Spanish rebuilt the mission, they did so according to the specifications of an army fort.

[Image from Missions California.]

Although the first American English colonists wouldn’t arrive until the middle of the nineteenth century, the earliest settlers arrived in the Los Angeles Basin in 1769. Gaspar de Portolá and his expedition set up camp along what is now called the Los Angeles River. The site was eventually given the name El Pueblo de la Reyna de Los Angeles (the Town of the Queen of the Angels).

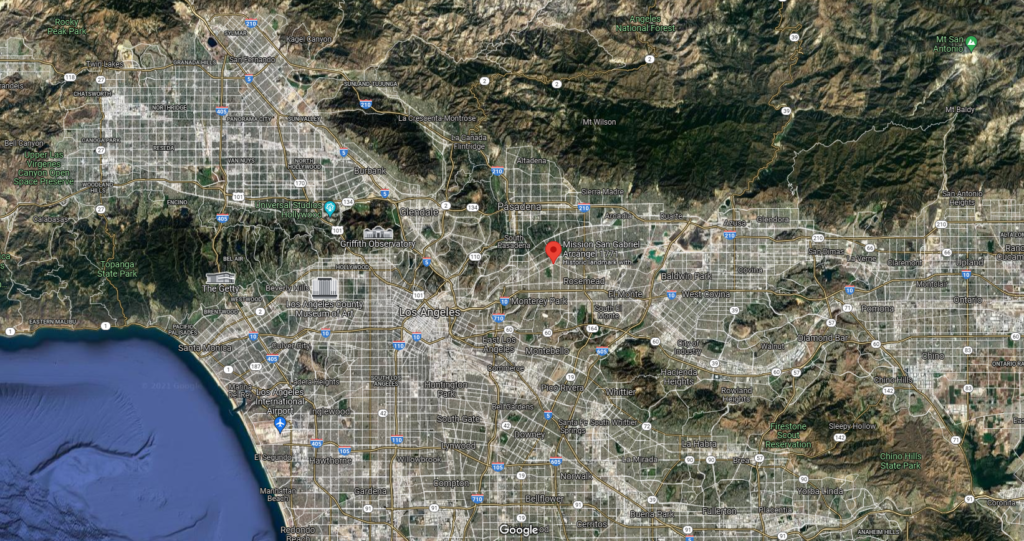

The Mission San Gabriel – which gave the Tongva their Spanish appellation of Gabrieleños – was built in 1771. Like its San Diego predecessor, the Mission is not in its original location. It moved to its current site after a flash flood ruined the original Mission complex.

[Aerial view from Google Maps.]

The rebuilt Mission was close to the Tongva settlement of Shevaanga.

Unlike their eastern counterparts, the Tongva and other California natives were not displaced from their traditional lands by forced relocation. Like their eastern counterparts, however, their population was decimated by diseases introduced by the Spanish. Abuse and attempts at forced conversion further reduced the native population throughout the state from an estimated 300,000 to a few tens of thousands. Today, approximately 4,000 people identify as Tongva or Gabrieleño.