In some of the previous entries about early human habitation in North America I’ve explored some of the evidence regarding how and when the earliest people reached the continent so I won’t cover that ground again here. Instead, I’ll start by presenting the evidence for the earliest Paleoindian presence in and around SLC and in northern Utah and try to move them forward in time in some meaningful way.

Where the fellas chew tobacky?

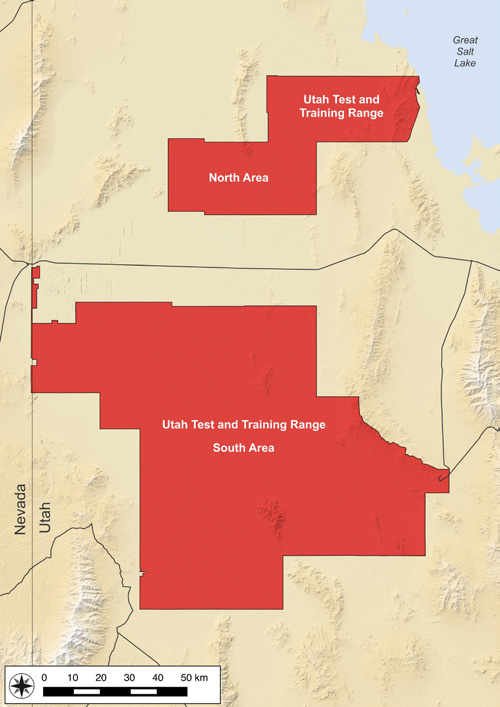

In his last term as a Senator, Orrin Hatch became determined to pass legislation that would expand the Utah Test and Training Range at Hill Air Force Base by more than 600,000 acres. (He began the process in 2014 and the legislation finally passed in 2017.) At the beginning of the legislative process,

[Map from Researchgate by Grant Snitker, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University.]

the U S Air force contracted with the Far Western Anthropological Research Group (FWARG) to survey the area and they made some remarkable discoveries.

If we hopped in the WABAC for a short journey 12,000 years into the past, we would find this part of Utah unrecognizable. The average temperature across the Great Basin was some 15 degrees cooler than at present and we would be looking at a landscape comprised of rivers, lakes, and marshy wetland ecosystems. In short, an area that was much more hospitable for the Paleoindians to inhabit.

What the researchers found was an open air campsite that they were able to date to 12,300 years before present. (They were able to carbon date a so-called “black mat” comprised of compressed marshy organic matter rich with the remains of plants, fowl, and fish.) The objects discovered included a finely crafted spear point nearly 10 centimeters long, stone flakes left over from the tool-making process, the broken bones of ducks and geese, and, most surprising of all, a collection of tobacco seeds.

The spear point, too large and over-engineered for hunting birds, provided the first evidence of mammoth hunting in the Great Basin. Confirmation came with the discovery of elephant residue on other stone points nearby.

[From westerndigs.org by Todd Cromar.]

However, for me, (and others) it’s the tobacco seeds that are, by far, the most intriguing discovery. Before this, the earliest known evidence of human tobacco use came from 3,000-year-old ceramic pipes from Alabama that contained nicotine residue and the earliest evidence of the plant’s domestication dates to about 8,000 years ago in South America. At this time, researchers don’t know whether the plant already existed in North America before humans arrived, or whether migrating humans brought it north.

The fact that the seeds were scorched presents probable evidence that the humans were using them in some manner. Whether they were chewing the seeds or smoking them in some way remains unclear. (There’s also the remote possibility that the seeds had been ingested by the waterfowl that the humans had eaten.)

If researchers can confirm a deliberate use of tobacco by these Paleoindians, it would deepen our understanding of the cultural significance of tobacco use by successor Native American people. (And on a side note, we have no evidence that the women would or did wicky wacky woo.)┬Ā

A few thousand years and the place is going to hell in a handbasket!

While the earliest evidence of humans living in Utah dates back about 13,000 years, over time, the climate changed and the people had to adapt. As the climate became drier and warmer, mammoths and other megafauna died out. During this period, termed the Archaic, evidence indicates that people began living in larger groups and, while still living a mainly nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, they chose to remain at or return to a single place for longer periods of time.

They developed spear throwing tool called an atlatl to hunt medium and small sized animals such as deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, and rabbits while also collecting pinyon nuts and other plants.

[Drawing of a hunter with an atlatl from georgiainfo.com.]

It’s from these Archaic people that we see the first petroglyphs such as this one in Horseshoe Canyon in Canyonlands National Park.

[From capitolreef.org.]

Ch-ch-ch-ch-changes.

Climate and environmental changes continued over several millennia and by about 500 BCE an entirely new culture and lifestyle arose in northern Utah that lasted until the middle of the 13th century. Archaeologists refer to this group as the Fremont culture so named for the river that flows through Capitol Reef Park. (Similar changes were happening in southern Utah but although there are some similarities, the Ancestral Pueblo culture that developed in the south is distinct from the Fremont culture of the north.)

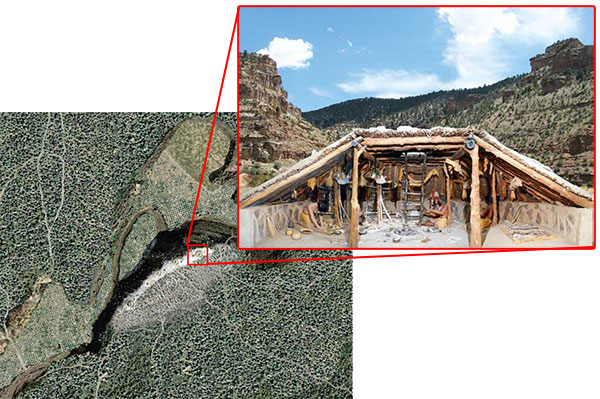

It’s at this time that we begin to see elements of agriculture incorporated into the still principally hunter gatherer lifestyle. The Fremont started growing corn, beans, and squash along waterways and floodplains. They lived in natural rock shelters and pit houses. Per Utah State University Eastern,

A slab-lined pit house is the most common house type encountered in the archaeological record of the Fremont culture. A shallow pit was lined with stone and covered with a wood and mud superstructure. This type of semi-subterranean structure would provide a sheltered space that was easier to heat in the winter and kept cooler in the summer. These pit houses are generally found in small hamlets of two to ten households on high ground overlooking floodplains.

It might have looked like this:.

[Drawing of a pit house from: Utah State University Eastern.]

This culture also produced distinct pottery that had smooth, polished surfaces or corrugated designs pinched into the clay. In a different type of early technology, the Fremont manufactured moccasins that that provided not only warmth but added traction on slippery surfaces by using the lower-leg hide of large animals, such as deer or bighorn sheep and leaving the dew claws intact. However, they are probably best know for their unique basketry. The style is called a one-rod-and-bundle and used native fibers such as willow, yucca, and milkweed.

[One-rod-and-bundle basket photo from NPS by Chris Rountree.]

For some reason, the Fremont culture didn’t adapt well to a climate that continued growing drier and hotter and they gradually faded away making room for a new Late Prehistoric culture called Numic because of the language they spoke. By 1250, the Fremont culture had disappeared. It’s not known whether it was subsumed, conquered, or merged with others in a process called residential cycling.

With the exception of the Washo, the language of all of the Indian people of the Great Basin belong to the Numic division of the Uto-Aztecan language family. The Numic languages appear to have further divided into three sub-branches – Western, Central, and Southern – about 2,000 years ago. Linguistic and archaeological evidence suggests that the Numic-speaking people spread into the Great Basin from southeastern California.

In time, these bands formed the Great Basin tribes – Shoshone, Bannock, Gosiute, Paiute, and Ute – that the first Europeans encountered when they began their exploration and settlement of the area in 1776. The first major exploration was the Dominguez and Escalante Expedition that set out from Santa Fe, New Mexico on 29 July 1776 seeking a new overland route to a Catholic mission in Monterey, California. For reasons I won’t detail here, they had to turn back soon after crossing into present-day Utah from today’s Colorado near what is today Dinosaur National Monument.

Among the Europeans who trickled into the area over the ensuing decades was Jim Bridger who is the first European known to have seen the Great Salt Lake. (I dedicated a section of this post to Bridger.) But the earliest European settlements came with the arrival of Brigham Young and the LDS Church in 1847.

According to the Book of Mormon, the Native American tribes inhabiting Utah, whom they called Lamanites, were descendants of a rebellious Israelite named Laman and their redemption was a prophecy to be fulfilled and a scripture to be vindicated.┬Ā Thus, hoping to minimize tensions between the groups, Brigham Young announced a policy of friendliness and fair dealing with the tribes.

[Photo from NYPL – Public Domain.]

As well intentioned as it was, neither side treated the other with fairness and respect and when Utah officially became an organized American territory, interaction with the native tribes came under the jurisdiction of the federal government. The situation soon deteriorated into decades of wars and skirmishes between the groups – a circumstance that never ended well for the indigenous people.