Kind of like the governor of Virginia.

Transliteration is challenging. It’s often tricky and misleading and the geographical focus of today’s post presents just this sort of problem. In the previous post, I identified the place as Kostenki which is how English speakers would locate it if they put the term into a map search. In Cyrillic, it’s written Костенки. If you copy and paste this into, say, the Google translation app, the pronunciation you hear for the Russian sounds something like “kuhs-YUHN-gih” or, to my ears a little like the surname of Virginia’s current governor, Glenn Youngkin. The audio for the English half of the Google translation says, “Kuh-STAIN-key.” As far as I’m concerned, you can pronounce it any way you like.

What makes Kostenki important?

At the end of the previous post, we left a group of hominins buried under several meters of volcanic ash near the medieval Georgian town of Dmanisi. When we arrived in Kostenki, we’d traveled not only 1,700 kilometers but nearly 1,800,000 years. (That, in and of itself, is a cool trick.) We’re now less than 600 kilometers from Moscow though we’d have to wait between another 30,000 to 35,000 years to see its earliest Neolithic settlements. (Moscow as a place is first mentioned in writing in 1147 when the prince of Suzdal. Yuri Vladimirovich Dolgorukiy hosted a great banquet for his ally the prince of Novgorod-Seversky “in Moscow.” This is generally taken as the year of the city’s founding though the area was clearly inhabited long before that.)

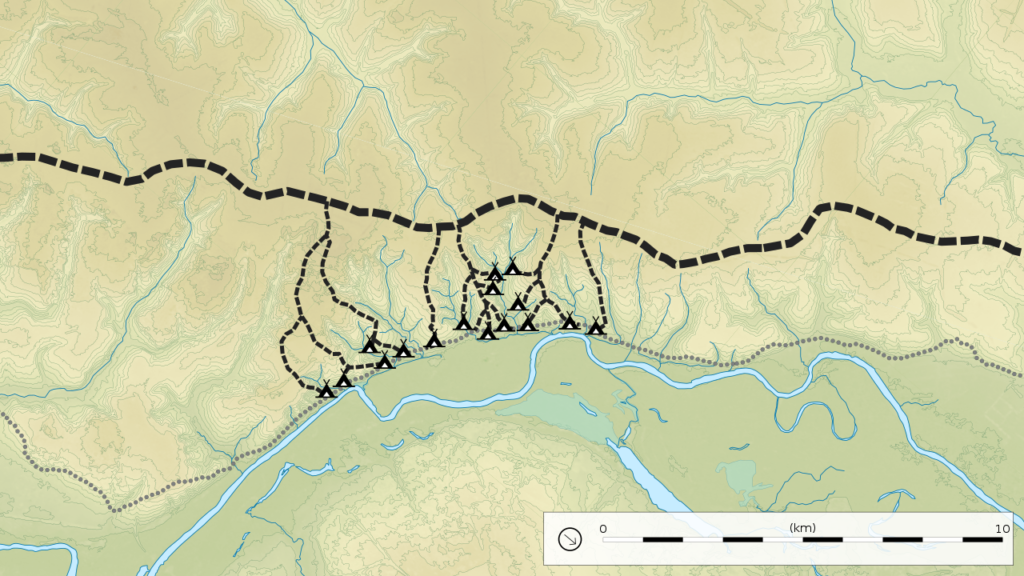

Had I thought about some of the migratory routes of hominins from Africa into Eurasia that I studied and presented in the second Beijing supplement, the discovery of an Upper Paleolithic site somewhere in western Russia shouldn’t have surprised me but it did. And the complex at Kostenki (actually Kostenki-Borshchyovo) is a rich one with 26 uniquely identified paleolithic sites some of which appear on the map below.

[Map from Wikipedia By Pedro P Palazzo – Own work – CC BY 4.0.]

Two characteristics make the site particularly useful and fascinating. The first is that, with human bones and artifacts dated to 45,000 years ago, it is the earliest known settlement of modern humans in Europe. The second is that the entire complex shows humans living in the area for a minimum of 15,000 to 20,000 years.

An unlikely place to settle.

Take a moment to recall the map of human migration from Africa in the aforementioned second Beijing supplement. It posited that modern humans began a mass migration north between 100,000 and 60,000 years ago. But what if that migration began a little later. The earliest H. sapiens remains lie in East Africa’s Great Rift Valley with an age of 160,000 years.

Sediment cores taken from that region show that the climate was quite variable but generally characterized by long droughts punctuated by brief periods of rain. These extremes appear to have prompted periods of rapid development in stone tool technologies. At some point it appears that groups of humans set out perhaps in search of more stable environments.

One day, while visiting the Port Elizabeth Museum in South Africa, Alan Morris of the University of Cape Town noticed an undated skull. He later brought it to the attention of Robert Grine an anthropologist at SUNY Stony Brook who applied optical scanning and uranium dating methods to date the skull at approximately 36,000 years. And here’s where things get curious. Osteological analysis of the cranium indicates that it has more in common with the Upper Paleolithic skulls uncovered at Kostenki than with other Subequatorial African groups. So it appears that our ancestors left the Great Rift Valley and traveled both north and south. (Osteological analysis may include the identification of human remains, inventory, minimum number of individuals, interpretation of pathological conditions, trauma interpretation, population demographic structure, and other analyses.)

[Map from Cambridge University Press.]

If this is indeed the case, consider the journey that these ancient people made as they wandered northward beginning somewhere near the Horn of Africa in the black and white section of the map above. Those who finally settled in and around Kostenki traveled some 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles) before settling in one of the coldest, driest places in Europe and survived there for millennia.

What’s been found there:

Once again thinking of the map in the Beijing supplement, there’s little doubt that Neanderthals inhabited Europe long before the arrival of H. sapiens so it might be reasonable to ask how scientists can be certain that the bones and tools found at Kostenki indeed belong to H. sapiens and not H. neanderthalensis. The question has a twofold answer.

First, while it’s true that the isolated teeth found in the earliest level of the excavation are, as one scientist put it, “notoriously difficult to assign to specific human types”, the accompanying artifacts are, “unmistakably the work of modern humans.” According to Doctor John Hoffecker of the University of Colorado at Boulder, “Unlike the Neanderthals, modern humans had the ability to devise new technologies for coping with cold climates and less than abundant food resources.” Second, in the 21st century, scientists can make wide use of the human genome.

Like the site at Dmanisi, a volcanic eruption preserved the Kostenki site. In this instance, it was the Campanian Ignimbrite (CI) eruption 39,280 years ago.

[Map from Wikimedia Commons By Wikirictor – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.]

(It may seem hard to believe that a volcanic eruption attributed to the Phlegraean Fields volcano near present day Naples, Italy could spread ash to a site more than 2,700 kilometers away. However, this particular blast is classified as a Level 7 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index. This should provide some idea how big a Level 7 V E I is.)

[Chart from USGS.]

The Kostenki site is best known for artifacts and remains from above the CI tephra. Still, items recovered from below the tephra are almost certainly the work of modern humans. They include burins, large retouched blades, end-scrapers, and micro-blades as well as bone awls and point fragments, and various ornaments such as a carved ivory piece that may represent the head and neck of a (unfinished) human figurine.

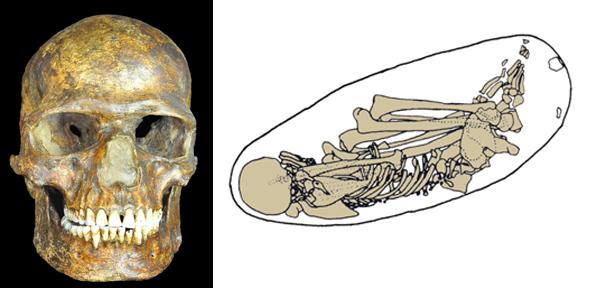

Additionally, a skeleton discovered in the later part of the 20th century has recently been dated to 37,700 years which makes it one of the oldest human burials in Europe.

[Kostenki 14 burial skull (left) and illustration of the burial (left). Credit: Peter the Great Museum (left) and Philip Nigst (right, redrawn after Klein, 1969).]

Among the more fascinating discoveries at Kostenki are the so-called Venus statues

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons BY Don Hitchcock CC BY-SA 4.0.]

and quite recently the mammoth bone structure.

[© AntiquityPublications Ltd from-Archaeology.org.]

This type of concentrated ring of mammoth bones – of which there are about 70 in the central East European Plain – is usually several meters in diameter. They are almost always surrounded by a series of large pits that are interpreted variously as evidence for the storage of food or bone fuel, rubbish disposal or simply as quarries for the clay, sand, and silt used in their construction.

The Kostenki Project of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge has more information and some excellent photos and drawings. I certainly encourage you to use the link if you’re interested.