Sometimes I don’t know when to stop.

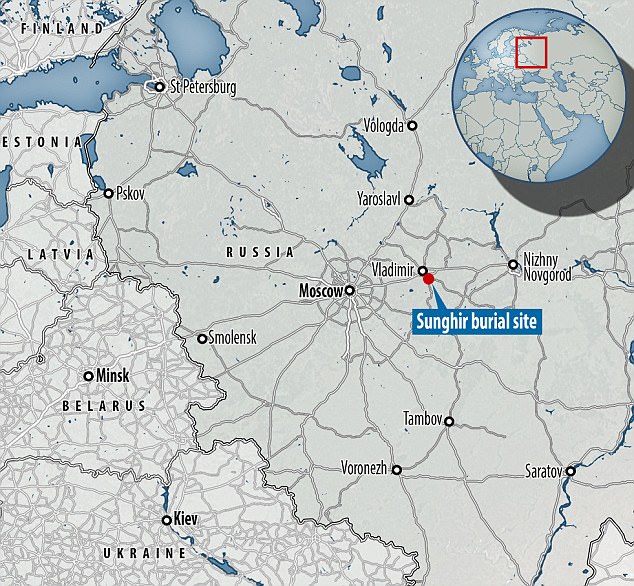

In supplements two and three of the Moscow segment of my Olympic cities tour, we met some likely H. erectus hominins at Dmanisi and some early modern humans at Kostenki. But Dmanisi is technically in Georgia not Russia and is more than 2,200 kilometers south of Moscow and although Kostenki is much closer and would quite possibly be on our route if we were walking from Dmanisi to Moscow, it’s still almost 600 kilometers south of Moscow so we haven’t gotten overly close to Russia’s capital city and Olympic host. Hence, our next stop will be at Sungir – an important ancient site a mere 200 kilometers east of our ultimate destination – before taking a look at some of the evidence for more recent Neolithic habitation in and around Moscow.

Let the Сунгирь shine.

One day in 1955 a group of workers was digging through the clay at a quarry on the outskirts of the city of Vladimir, Russia when they happened upon some unexpected objects that led them to call upon a local paleontologist.

[Map from DailyMail].

The quarry work stopped and excavations began at the site named for a stream not far from the Klyazma River. The area excavated over the ensuing two decades covered approximately 4,500 square meters (about 1.1 acres) and it became one of the most important and iconic sites of how Upper Paleolithic humans in Europe treated their dead.

In archaeology, a cultural layer is a layer of earth at sites of ancient human habitation that contains traces or remains of human activities at that place. They can range in depth from just a few centimeters to more than 30 meters generally depending on the temporal length of human habitation. They are excavated in an effort to reconstruct the history of the settlement and Sungir has such a layer. Surprisingly, this is among the least studied areas of the site.

An analysis by Cambridge University published in the journal Antiquity, describes it this way:.

Sandwiched between layers of Late Pleistocene sandy loess, the <0.2- to about 1m-thick Cultural Layer is a palimpsest of an undetermined number of individual occupation levels, many of which were merged by cryoclastic (freeze-thaw) processes. In addition to the Cultural Layer, there were pits, hearths and two graves dug into the underlying loess. All of the human remains derive from either the Cultural Layer or the graves dug into the loess below.

It is the two graves that have drawn the most attention.

The big three.

Using radiocarbon (C14) dating methods on the human and other faunal remains, scientists have placed the minimum age of the graves at Sungir at 30,000 years BP and the calibrated age at 34,000 years BP. This age corresponds to an interstadial period known as Greenland 6. (An interstadial period pertains to a temporary thaw in the middle of an ice age and shouldn’t be confused with an interglacial period when glaciers retreat between ice ages.) This allowed the people to dig graves and pits into what would otherwise have been frozen loess. In addition to the carbon dated fauna, studies of pollen and spores called palynology and studies of sedimentation confirm the time frame.

The remains of at least 10 individuals have been discovered and identified at Sungir but the most spectacular belong to this fellow:.

[Photos from Cambridge.org and Archaeology.com.]

Found in what has been labeled Grave 1, it is the largely complete skeleton of a 35 – 45-year-old male laid on his back. His body was extensively covered with ocher. The arrow in the lower photo points to an incision in the lower neck that would have been the cause of death. In addition to the ocher, the body was accompanied by what was likely to have been extensive personal decoration – some of which may have been sown on to his clothing. The items include some 3000 mammoth ivory beads some with intact strings, 12 pierced fox canines on his forehead, 25 mammoth ivory arm bands above the elbows and wrists, and a single pigmented schist pebble pendant on his chest.

According to Natasha Reynolds, an archaeologist at the University of Bordeaux in France, who specializes in the European Upper Paleolithic, “Sungir is the first point in time where we see these complex mortuary behaviors reflected in the European archaeological record.”

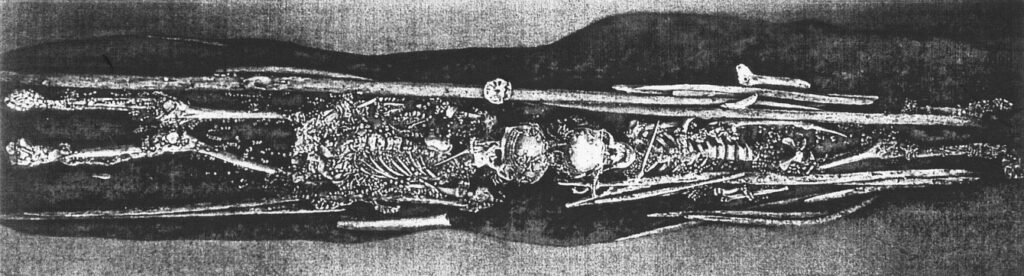

[Photo from Wiley.]

is perhaps even more spectacular from an archaeological viewpoint. The bodies, laid head to head are those of two boys one about 12 years old and the other aged 9 or 10. The artifacts that accompanied this burial were even more elaborate. It was essentially a treasure trove comprised of more than 10,000 mammoth ivory beads, more than 20 armbands, about 300 pierced fox teeth, 16 ivory mammoth spears, carved artwork, deer antlers and two human fibulas laid across the boys’ chests.

Even more remarkable, however, is that both of these boys were disabled. One study of their remains did an analysis of their dental enamel and found that both boys experienced repeated periods of extreme stress. The thighbones of the younger boy are extremely bowed and short while his companion’s teeth had almost no wear. The latter is noteworthy because people from this time wore their teeth down quickly so it’s possible that this child was bedridden and the group was feeding him soft foods.

Lawrence Straus, a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of New Mexico told Live Science, “…people with disabilities or pathologies that would have limited their full functioning are getting some amazing treatment.”

Comparing the known graves has found some people who, like the man and two boys had elaborate burials, while others had only a few fox canines and mammoth ivory beads and still others had nothing. From these burials we can at least infer a measure of social complexity because if people were treated differently in death the same would have likely been true in life.

Lyalovo.

At last we’ve reached Moscow and its suburbs or, as the Russians call it, Moscow Oblast. And now we can take a brief look at a Neolithic culture called Lyalovo. We’ve come forward in time some 30,000 years from the burials and relics at Sungir to about 4,000 BCE. Artifacts identified as Lyalovo show that this group had a territorial range mainly between the Volga and Oka Rivers.

[Map from Wikimedia Commons – unattributed.]

It’s so named because an artifact discovered in the 1920s in the village of Lyalovo in the Solnechnogorsk District of the Moscow Oblast is the first attributed to this group. The Lyalovo group was part of a larger European Stone Age culture known as the Comb-Ceramic culture that’s found across the northeast part of the continent.

[Map fom indoeuropean.eu.]

The descriptor Comb-Ceramic derives from the typical decorations found on their ceramics which look like imprints from a comb. The photo below shows a typical Lyalovo receptacle.

[Image from mos.ru.]

The region’s climate at that time was likely quite similar to today’s climate in and around Moscow and likely sported dense forests of pine and birch with ample floral and faunal diversity for a hunter-gatherer society. The birds and fish of the river systems and glacial lakes provided their main source of protein.

The Comb-Ceramic cultures survived until about 2000 BCE and 3,150 years later, Yury Vladimirovich Dolgoruky would host his “great banquet” in Moscow.