I’ve written before about some of the reasons I include posts about subjects such as geology or archaeology that are seemingly peripheral aspects of travel. One I haven’t mentioned is that in the course of learning about a place in such detail, I continually unearth facts that surprise and, in some way, delight me. This happened as I was completing my research about the earliest humans to inhabit the area in and around Calgary.

But first let’s talk about Bison.

In past entries we’ve encountered two ideas that we need to draw together. One is that the Earth experiences periods of glacial advance and retreat. The other is that significant glaciation has often connected North America and Asia across the Bering Strait. This connection was almost certainly one of the migratory routes taken by early humans.

Thinking about this, a natural question might be, “Couldn’t other species have used this route, too, and if so, what animals engaged in cross continental migration?” The answer to the first part of the question is absolutely yes and one answer to the second part is that one of the animals that followed this route from Siberia was the Steppe Bison.

Some of these bison traveled south fairly quickly where they apparently evolved into a distinct species – the giant long-horned bison – since no fossils of this species have been found north of the U S – Canadian border or in Siberia. And giants they were!

[Comparative bison images from Allaboutbison.]

The first steppe bison migrated about 195,000 years ago. (Of course the migration route wasn’t a one way highway. Fortunately for their species, horses and camels that had evolved in North America crossed into Asia. You see, while bison survived the large mammal extinction event that happened after the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) in North America, the remaining horses, camels, mammoths, and others did not. There’s also a suggestion that humans might have pushed some of these species into extinction as this 2015 story from the CBC shows.)

Soon after the beginning of the LGM (between 45,000 and 21,000 years Before Present or BP) a second wave of bison migration occurred. As some of the steppe bison were beginning to evolve into their smaller descendants we see today, the advance of glaciers across Canada about 30,000 years ago created a barrier that separated the northern populations from those that lived in the southern part of North America. Near the end of the Pleistocene, around 13,000 years ago, bison populations in Yukon and Alaska were dwindling while groups to the south of the glaciers were expanding and ultimately evolved into their modern forms.

[Bison photo from BillingsGazette.]

What, you may be wondering, does this have to do with human migration? They are connected in two ways. First, think about the time the first humans were crossing Beringia – generally believed to be about 13,000 years ago. It’s possible that human hunters might have been the final nail in the extinction coffin for that dwindling northern population.

Second, the southern population was continuing to evolve and expand. In fact, other than humans, bison were the most successful mammal to colonize North America after the LGM. By feeding on grasses and woody plants they quite literally changed the ecosystem and increased the biodiversity of the prairies. This rich biodiversity and the bison themselves supported the continent’s first humans for thousands of years.

South to Alberta.

Notwithstanding the claims that a stone knife, mastodon bones, and fossilized dung found in an underwater sinkhole show that humans lived in north Florida about 14,500 years ago, there’s some controversy regarding the age of the earliest broadly accepted place occupied by humans in the Americas. That location is Bluefish Caves in the territory we call Yukon.

[From Google Maps.]

There, archaeologists found chipped stone artifacts in sedimentary layers containing the fossilized bones of extinct animals. Radiocarbon dating determined an age of at least 10,000 to 13,000 and possibly 15,000 to 18,000 years ago. The artifacts are similar enough to those produced in northeast Asia in the late Paleolithic that it’s reasonable to infer that these tools represent the territorial expansion of Asian hunter-gatherers across Beringia and into Alaska and Northwestern Canada. Certainly these hunters would have followed the migratory routes of the bison and other large mammals.

Even during the LGM, because of a dry climate and insufficient snowfall, much of Alaska and Yukon remained unglaciated and, although a cold tundra, habitable. It remains an open question whether people similar to those who occupied the Bluefish Caves or their descendants expanded farther east or south into North America. One possible route was a narrow ice-free corridor that may have existed between the Cordilleran glaciers of the western mountains and the Laurentide ice sheet extending from the Canadian Shield that would have allowed for early migration. Another possibility is that a corridor may have opened only after the glaciers began to melt and retreat about 15,000 years ago.

A third possibility is a route along the Pacific coast to the west of the Cordilleran glaciers. No early sites have been found along the route of these corridors, but certainly by 12,000 years ago some groups such as the Clovis culture had penetrated the western and southwestern United States leaving behind evidence that they hunted the large herbivores that grazed the grasslands and ice-edge tundra of the period.

But let’s get back to Canada where the earliest human artifacts found in southern Alberta date to about 13,300 years BP. In order to move south, people living so far inland would have required an ice-free corridor. Seeking to discover when such a corridor opened, a group of researchers started looking at bison remains.

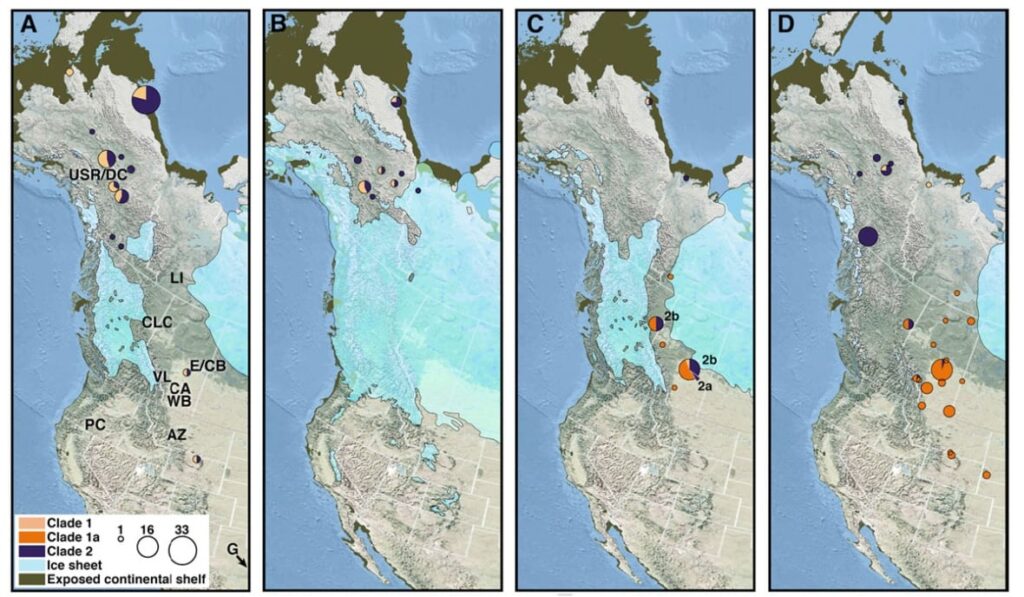

The four panel map above by Andre Soares and Robin Woywitka of the U S NPS and USGS traces the genetic clades of bison from 25,000 years ago in panel A to 12,000 years ago in panel D and shows a migratory corridor that both the bison and the humans could have plausibly followed. (A clade is a monophyletic natural group of organisms that are composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants.) Although other herbivores and predators would have been present, the researchers focused on the bison because as noted above, bison in the north and bison in the south were separated from one another by the ice sheet for thousands of years making them genetically distinct.

Peter Heintzman of UC Santa Cruz analyzed the DNA from about 190 fossils borrowed from the Royal Alberta Museum to determine which came from which. His results indicate that southern bison started moving north around 13,400 years ago and that the two populations began overlapping in the corridor between present day Calgary and Edmonton around 13,000 years ago. And, if the two bison groups were meeting, it’s possible two Paleoindian human groups were meeting as well.

And their descendants.

Today a number of tribes are identified as indigenous to the southern Alberta plains. These include Kainai, Nehiyawak (Cree), Tsuut’ina, and Nakoda. From the time of their earliest settlement until about 200 CE, they hunted mainly with spears and the atlatl. It’s at this time that the bow and arrow, introduced by a distinct culture called Avonlea, appears. The origin of this group is a subject of considerable debate among archaeologists with some believing they originated from the Mississippi Valley. Others point to similarities with ceramics from the Eastern Woodlands of Manitoba and Minnesota and still others contend that they developed from other locations such as Pelican Lake in Manitoba. Wherever their origin, the Avonlea culture had a great impact on the local tribes.

Europeans didn’t reach this part of Canada until the later part of the 18th century after which, as it has always been, indigenous life would be permanently altered in ways with which we are all too familiar.