Africa. China. Africa.

In his 1871 book The Descent of Man, Charles Darwin became the first person to propose the idea that it was “probable” that Africa was the cradle of humans and, in fact, Africa has been the focus of evolutionists and paleoanthropologists since the early part of the twentieth century. And while the “Out of Africa” idea held sway, the questions of how and when different branches of the hominid tree evolved to become Homo sapiens (H.sapiens) or whether there was interbreeding with other evolutionary limbs such as Neanderthals remained open.

Then, in 1921, Otto Zdansky, an Austrian paleontologist, discovered a human tooth at Longgushan a hill complex in the village of Zhoukoudian just 60 kilometers (37 miles) southwest of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Researchers continued exploring the site and in 1929 Chinese anthropologist Péi Wénzhōng discovered a relatively complete skullcap and the discovery was labeled Peking Man.

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons by José-Manuel Benito Álvarez Own Work – Public Domain.]

Although Peking Man belonged to the branch called Homo erectus, Chinese scientists now used this 400,000 year old fossil to put forth a claim that modern humans arose in this part of Asia. The battle was on. I won’t enter into the details but, in the end, Africa more or less won although that doesn’t mean Asia and China don’t still have a lot to say in the matter.

How the H. did we happen?

My previous discussions of early humans coming to occupy a given geographical location have come chronologically long after H. sapiens came to be the dominant species of hominin on Earth. Although I could start in a similar place in discussing China and the area around Beijing, the picture is so complex that I think it merits at least a fuller, if still cursory, overview of human evolution.

It’s easy and perhaps common when thinking about the sequencing of the human genome to focus on its importance in health and medicine but it has also had a significant impact on genetics, evolutionary biology, and paleoanthropology. Before scientists had the ability to sequence and analyze human DNA, the standard route of human evolution followed a relatively direct path from the rise of H. erectus in Africa about two million years ago to the rise of Homo heidelbergensis a million and a half years or so later.

The story then goes like this: About 400,000 years ago H. heidelbergensis split into three groups.

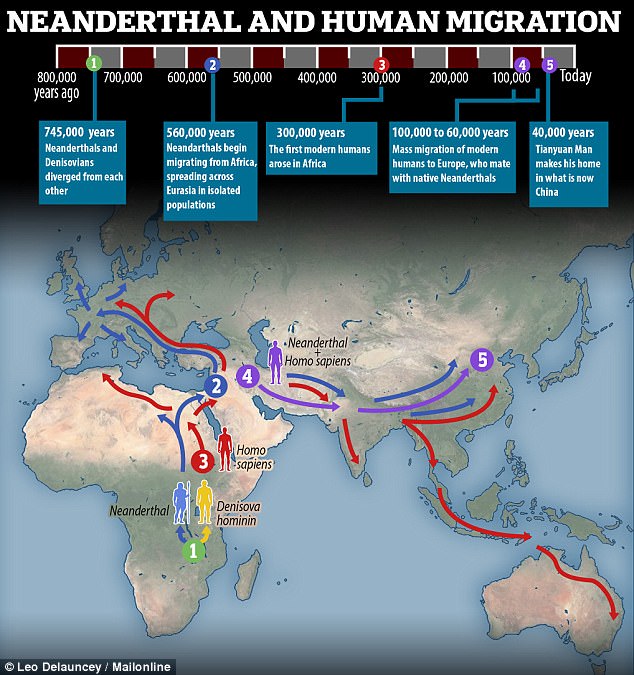

[Map from from DailyMail.]

One remained in Africa and over a period of about 200,000 years evolved into H. sapiens while a second group wandered into the Near East and Europe evolving into Neanderthals and, in something of a surprise, the third appears to have traveled farther east to become a group discovered in Siberia in 2010 called Denisovans. (They carry this identification because the first bone identified from this hominin group came from the Denisova Cave in Russia not far from its borders with Kazakhstan and Mongolia.) Then, some 60,000 years ago, H. sapiens left Africa, populated Eurasia, and ultimately displaced the local hominins with minimal interbreeding. Recent genetic analyses have changed this view and this short video from cell.com provides a worthwhile summary.

As the video explains, DNA evidence shows that H. sapiens interbred with other hominins across Eurasia with considerable frequency and fecundity.

(Note: The intent of the map above is limited to tracing interactions/interbreeding between H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis. The route of the Denisovans isn’t shown but they migrated generally north and east with their territory widely ranging from Siberia to southeast Asia including the Indian subcontinent.)

The lines become blurrier still as more and more Chinese fossils have been studied since the 1980s. These fossils point to substantial populations of hominins in east Asia dating back nearly a million years with features placing them between H. erectus and H. sapiens. This has forced scientists to reconsider the notion of a relatively straight line from H. erectus to H. heidelbergensis. In fact, some researchers look at these as transitional forms that appear to have persisted for hundreds of thousands of years in China until they eventually show enough modern traits to be classified as H. sapiens. Of course, nothing is certain and other researchers posit that rather than remaining in the Middle East this group simply continued migrating into east Asia.

Eventually unearthing the truth requires reconciling the differences between the DNA evidence, the fossil record, and the once standard interpretation. We aren’t there yet and we need to keep in mind as one researcher quoted in Scientific American said, “Fossil interpretations are notoriously problematic.” Reaching conclusions from DNA studies isn’t much easier but still, we need to consider the thoughts of Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, “Asia has been a forgotten continent. Its role in human evolution may have been largely under-appreciated.”

It’s complex-icated.

Complex and complicated are two words that appear regularly in almost any examination of the literature surrounding the points at which European, Asian, and even Native American populations became distinct to varying degrees. (I’ve excluded Africans because genetically humans outside of Africa carry up to a four percent match with Neanderthal DNA but no Neanderthal DNA has been found in Africans.)

The caves in the area around Zhoukoudian must have offered some sort of significant survival advantages because in 2003 researchers uncovered the remains of an early modern human nearby at Tianyuan Cave. (The term early modern humans generally refers to humans whose form and structure {morphology} is similar to present-day humans. They first appear in the Eurasian fossil record about 45,000 years BP.)

[Photo from Genetic Literacy Project.]

By about 45,000 years ago early modern humans had spread across Eurasia and estimates of the age of the Tianyuan man remains ranged from 39,000 BP to 42,000 BP and were generally tagged at 40,000. Some years later scientists generated genome-wide data from him and this is where the story gets fun.

When paleoanthropologists initially unearthed Tianyuan man, they thought he was the love child of a human and a Neanderthal but his DNA analysis showed a match of between four and five percent marking him distinctly as an early modern human. But the picture gets richer still. One might find it unsurprising that he is more related to present-day and ancient Asians than he is to Europeans. However, he shares a significant number of alleles (An allele is one of two, or more, forms of a given gene variant.) with a 35,000-year-old European called GoyetQ116-1.

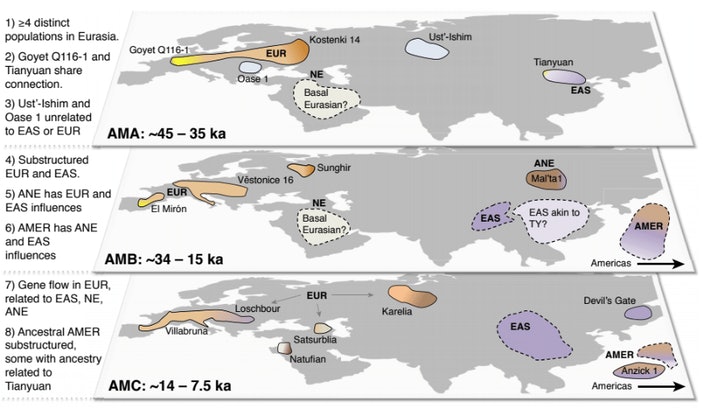

[Map from Inverse.]

Scientists compared the DNA sequences of 20 individuals revealing that between 15,000 to 34,000 years ago, the humans living in Eurasia had genetic profiles similar to either Europeans or Asians. This made those Eurasians a distinct population and indicated that a genetic separation between Asians and Europeans happened at least 40,000 years ago. Given the physical distance between them, how then could 40,000 year old Tianyuan Man have so much in common with GQ116? There is, as yet, no definitive answer but this indicates that the separation between early Europeans and early Asians was likely not a single population split.

Around 7,500 to 14,000 years ago, the genetic gap appears to have shrunk. Larger numbers of humans show genetic similarities to both Asians and Europeans. This suggests that, during this time, the once-distinct Asian and European populations had interacted once again, thereby complicating the genetic and migratory history of these groups.

But Tianyuan Man’s genome has yet another surprise in store. You see, he shares more alleles with ancient and present-day Native Americans than with either ancient or present-day Europeans even if ancient and present-day East and Southeast Asians and Native Americans are all more closely related to each other than they are to Tianyuan Man.

Thus, it appears that Tianyuan Man derived from a population that was ancestral to many present-day Asians and Native Americans but postdated the divergence of Asians from Europeans. And it’s possible the descendants of Tianyuan Man were the ones who crossed the Bering land bridge to populate the Americas when glaciers began to recede during the last Ice Age.

All we can do is keep digging.